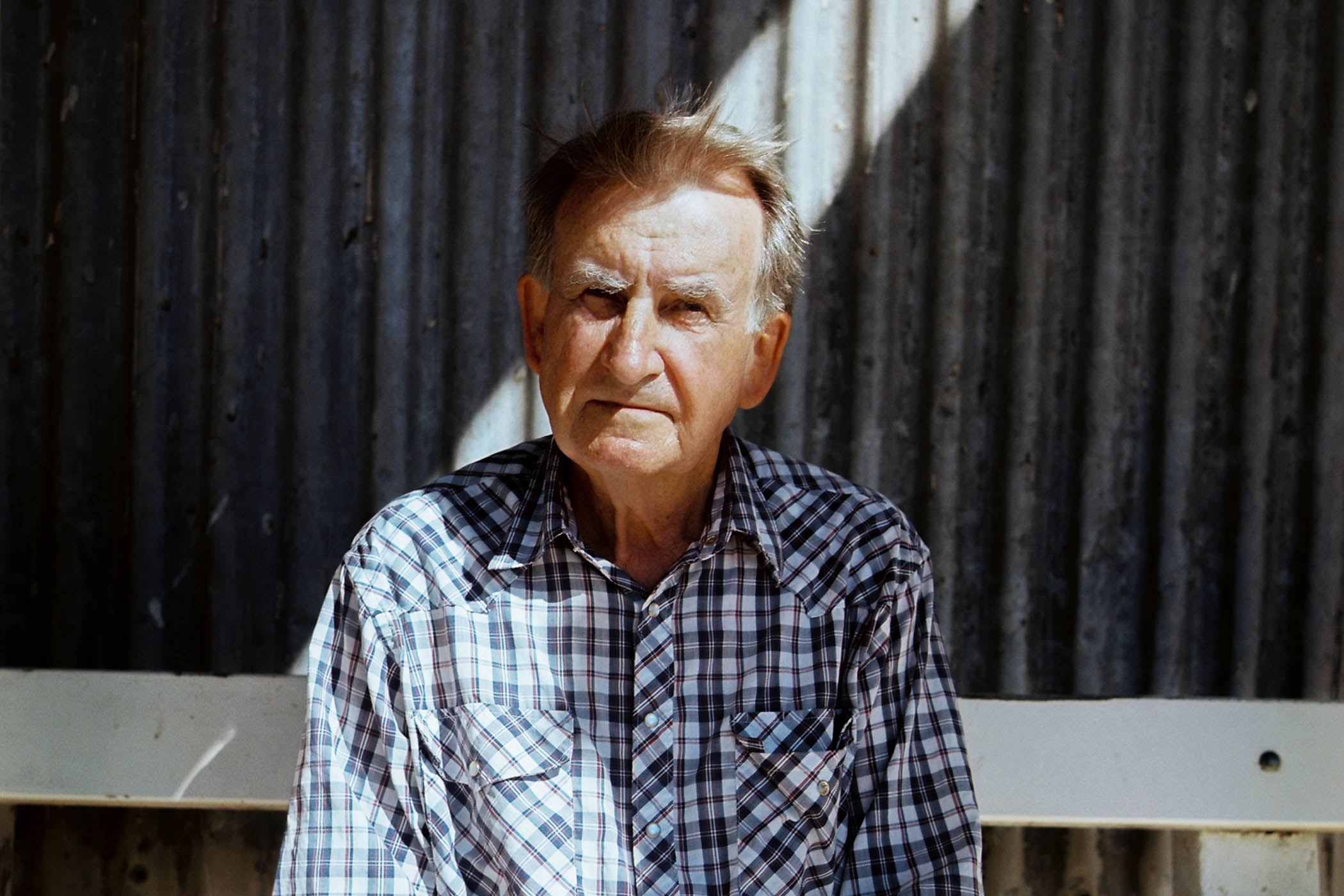

Gerald Murnane, 86, has been described as “the greatest living English-language writer most people have never heard of”. He found critical acclaim publishing fiction (including The Plains) in the 1970s and 80s. But since the 2010s, a revival of interest in his books – whose major themes are memory, religion, sex, reading and the Australian landscape – has brought him international renown. Landscape With Landscape, a collection of six stories that was brutally reviewed upon its 1985 publication, now appears in the UK for the first time. Murnane lives in Goroke, a remote village in western Victoria, Australia.

Critics have said your writing is “hard to describe”. How would you describe it?

Some years ago, I developed a primary distinction between two kinds of fiction: film script fiction and true fiction. Film script fiction gives the reader the impression that he or she is watching a film in his or her mind: “Rain fell incessantly. Occasionally a growl of thunder was heard in the distance. A lone, overcoated figure struggled against the downpour on a lonely piece of moorland.” What I call true fiction is not – and I repeat not – autobiography. True fiction is a true account of the contents of the writer’s mind. The true fiction version would be something like: “On a wet night in January 1943, Cyril Cosgrove was crossing a piece of moorland during a heavy downpour. He was going to visit his ailing mother, from whom he had been estranged for 25 years.” The difference is… well, it’s obvious, to an intelligent person. I write true fiction.

How do you feel about Landscape With Landscape now, 40 years after its publication?

I made things difficult for the readers of that book. The most difficult piece is the first piece, Landscape With Freckled Woman. I won’t say I regret it, but if I wrote it today, I would try to make that piece clearer. It makes perfect sense to me, but I can understand the hasty reading of the critic [in the Australian magazine the Bulletin] who savaged me.

What did that critic miss?

Most of Landscape With Freckled Woman is conjecture on the part of the chief character, a writer. He’s living in his mind, asking how a writer should react. The critic supposed that this man was planning to seduce these women. He missed that my characters struggle in this constant clash between the visible world and the invisible world.

Tell me about your “landscapes”, both mental and natural.

I often think of the American poet Robert Bly. He was a cranky bloke in many ways, but he said: “A person must learn to trust their obsessions.” I was obsessed with landscapes from early childhood. I watched American films not to see the action but to watch the prairies in the background. I’ve always been repelled by mountains. I have come to think of my mind as a grassland or prairie. It’s infinite in dimension.

How did it feel to be named as a candidate for the 2025 Nobel prize in literature?

I’ve got used to it by now, as much as I can get used to such a thing. I keep coming back to the 1990s, which was my lowest point. I can be quite petty. I take an almost vindictive pleasure in thinking that there are people who are still alive, who see my name connected with the Nobel prize, who didn’t even regard me as one of the top 20 Australian writers back then.

Why have you never travelled outside Australia?

What if God made an announcement: “You’ve all got to go back to the places that matter”? If it’s going to take me more than a day, I’d never make it.

You said that Last Letter to a Reader (2021) is your final book. Are you still writing?

I’ve never tried to use a computer. They just frighten me. And I can’t send emails. But I can use the basic functions of a smartphone. I’m using it now to speak, and I look things up on Google and Wikipedia. I send a few text messages and people send them to me, and at the end of each week, if a few have significance, I’ll transcribe them on my 60-year-old Monarch typewriter. They go into the chronological archive. So I’m still writing for my archives.

Tell me more about your archives.

I live with my son. He rents me a room, and it’s full of filing cabinets. The largest is the chronological archive, which is my life story. Then there’s my literary archive. The third is called the antipodean archive and that’s imaginary horse racing. Every evening I spend a couple of hours adding to it – maps of the towns, diagrams of the race courses, details of the jockeys, trainers and horses. When I’m dead and gone, no one will understand it. There’s no purpose in me explaining. Let it lie as it is, as a monument to my obsessions.

Which books have had the biggest impact on you?

I might have had a wonderful experience reading half a page of this book or two and a half pages of that book, but I don’t count as any significant event in my life the reading of a whole book. So I can’t answer that. For most of my life, reading a book seems to have been an excuse for writing in my mind a book that worked on my feelings even more than the thing in front of my eyes.

So which passages have most influenced you?

Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past is grossly flawed. It has passages so dreary that I hardly finished them, but also three or four passages whose effect on me was all powerful. And parts of World Light by Halldór Laxness, who won the Nobel prize in the 50s. Also, a book that I would read the whole of again: Hunger by Knut Hamsun. You might say: “What about Shakespeare?” Don’t even mention Tolstoy. I couldn’t read more than two pages of Tolstoy without wanting to be ill. He should have been arrested for writing War and Peace, the book’s so big. You shouldn’t write books like that.

Landscape With Landscape is published by And Other Stories (£14.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £13.49. Delivery charges may apply

Portrait by Morganna McGee

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Related articles: