It is widely accepted that we are living in the midst of an information revolution, as we come to terms with rapidly advancing digital technologies. The idea that we are also living in an “information crisis” is at the core of Naomi Alderman’s thought-provoking book Don’t Burn Anyone at the Stake Today.

Her aim is to explore two earlier information crises, and to draw lessons that might prove useful to us in today’s technological age, as we struggle to make sense of its impact on our politics, society and, more importantly in her view, psychology. Alderman is a novelist whose work includes the modern sci-fi classic The Power, which won the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2017. She has also had a career writing and developing computer games such as Perplex City and Zombies, Run!, and therefore brings an unusual perspective on the digital epoch. Anyone looking for a technophobic response to the present predicament will be disappointed.

The earlier crises she considers are the invention of writing around 5,000 years ago, and the printing revolution of the 15th century. These brought profound changes in the way humans were able to communicate and share ideas, but also changed us internally in how we assimilated and considered the ideas of others.

Each of the three epochs under discussion have altered us “psychologically, socially and emotionally in profound ways that simply cannot be reversed”.

“We live in a tidal wave of data, coming at us constantly,” Alderman writes of our own epoch, and this is making us anxious and angry. She is right on the money here: “We might end up expressing an idea online ... only to be jumped on by 50 people who know more and tell us that our ideas are stupid, old-fashioned and even prejudiced.” She encourages us to draw an analogy with the way people must have felt during the European Reformation, when, thanks to the spread of printing, new religious ideas continued to spring up – for example around transubstantiation and whether the Christian sacrament was transformed into the actual body and blood of Jesus Christ or was merely symbolic. You might discover that your neighbour thought very differently to you about this in much the same way that people on social media discover that the views of family and friends are diametrically opposed to their own.

Alderman stresses the role of public libraries ‘designed to try to serve the public, and not to hook us into an endless outrage-and-hype cycle’

Alderman stresses the role of public libraries ‘designed to try to serve the public, and not to hook us into an endless outrage-and-hype cycle’

Her analysis of the earlier information crises is interesting, but Alderman paints these with too broad a brush. The invention of writing, which began in the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia with the creation of Cuneiform script, took place over such a long period that it cannot really amount to a “revolution”. While the invention of writing (perhaps “inventions” would be a better word) was a fundamentally important development, Alderman perhaps misses a point: one of the first uses of Cuneiform was to document numbers, for the purposes of both commerce and taxation. This was the invention of data, used for managing populations and for monetary and ultimately political control. The first spreadsheets can be found in impressions made on clay tablets many thousands of years before Excel.

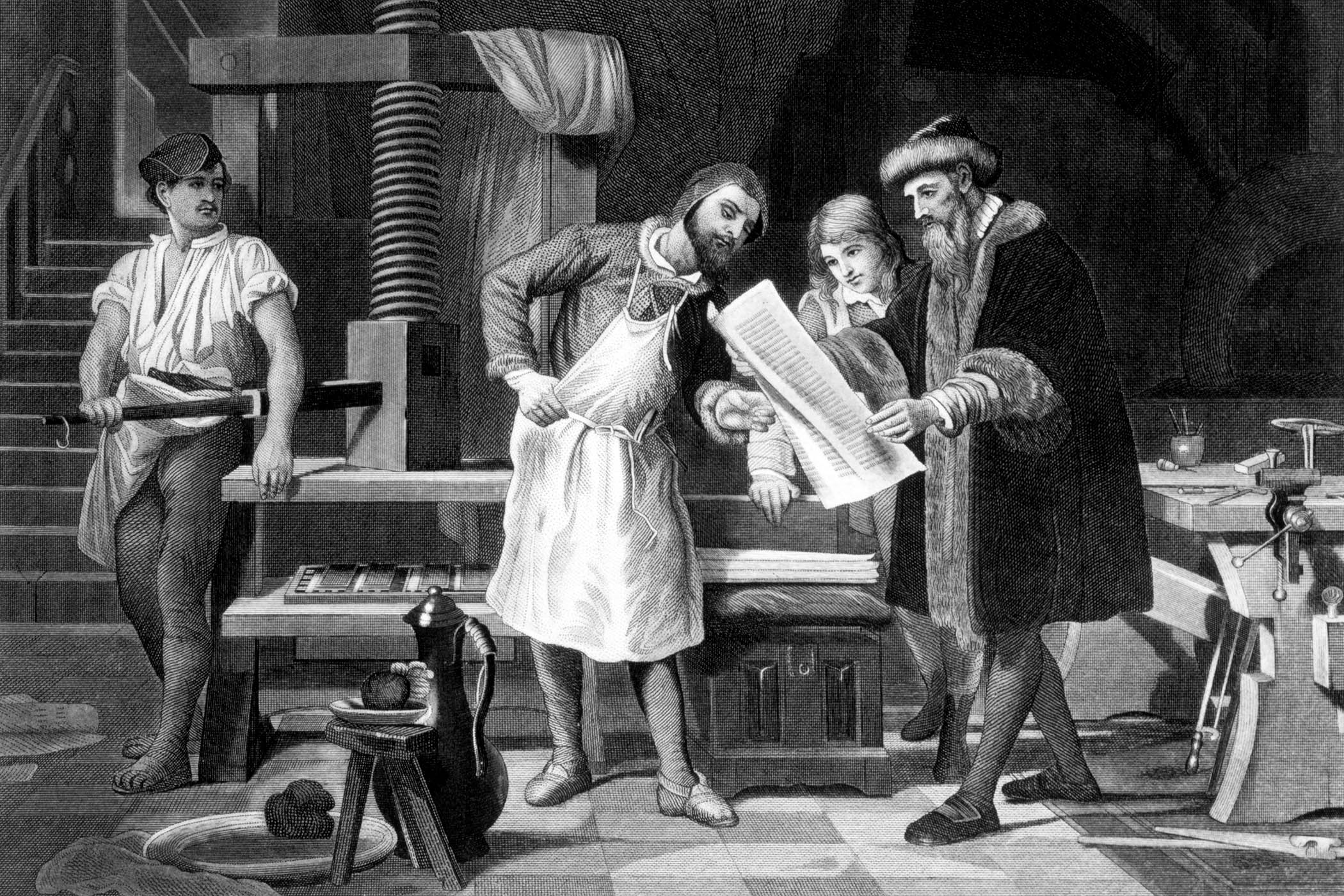

The book’s account of the advent of printing is similarly sweeping. Alderman acknowledges in passing that printing technology was developed first in Asia some six or seven centuries before Johannes Gutenberg developed his own means of reproducing texts mechanically. His Bible appeared around 1450 and spread rapidly across western Europe over the subsequent five decades, then across the globe. Alderman overemphasises some of these shifts, as her discussion focuses on the impact of religious and scientific ideas, with which the majority of the population did not fully engage (early print runs were very small and education was limited), unless mediated through the pulpit or the interpretations of the few literate members of society.

Alderman is most persuasive when discussing the impact of the current information crisis. She concentrates on what Tim Berners-Lee called “the semantic web”, more broadly known as Web 2.0. This heralded the age of the interactive internet as exemplified through the “datafication” of personal interactions with online resources, ranging from searching (especially via Google) to shopping (such as on Amazon) and social media – which is where Alderman focuses her discussion. These interactions have become linked through a technology known as ad tech, at first to target online advertising at users with greater accuracy, and then to predict a broader range of human behaviours, including voting.

Related articles:

An etching depicting Johannes von Gutenberg overseeing the printing of his Bible in the 15th century.

This is at the heart of the present crisis: what Shoshana Zuboff has termed “the age of surveillance capitalism”, in which surreptitious data profiling of individuals has been taking place over two decades. Algorithms are geared towards keeping users online by stoking controversy, and therefore driving advertising revenue and making companies exceedingly wealthy. Society has sleepwalked into a series of profound changes in the way information is created and disseminated.

What can we do about all of this? Alderman poses some potential solutions. This reviewer naturally found her arguments around the role of public libraries compelling: “A public library service has been designed to try to serve the public, and not to hook us into an endless outrage-and-hype cycle.” She even suggests extending the concept to a kind of public library smartphone, with features aimed to protect rather than exploit its users. In her chapter on misinformation she also advocates protecting other public institutions, such as the BBC. On the epidemic of loneliness being driven by the information crisis, her suggestions are simpler: “Your friends would like to hear from you.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Alderman points out that the successive information crises have allowed the spread of knowledge and ideas to become faster and more efficient, bringing many benefits. But she is also frank about the myriad problems this has caused. Her assessment of the future is sobering: she predicts more conflict and polarisation, and a further shift towards fundamentalism. She calls on us to resist these tendencies: talk to people and not AI; read a book instead of scrolling; and have the hard conversations that build relationships. What is vital now is a way of bringing these simple but wise ideas into public policy. In resisting the fracturing effects of the third information crisis, we need regulation to come to our aid.

Don’t Burn Anyone at the Stake Today (and other lessons from history about living through an information crisis) by Naomi Alderman is published by Fig Tree (£16.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £15.29. Delivery charges may apply

Richard Ovenden is Bodley’s librarian and the Helen Hamlyn director of university libraries at Oxford

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Portrait by Annabel Moeller; illustration courtesy of Universal Images Group/Getty Images