“Yeah, we’re lost.” Twenty minutes into my walk around the Prado with the French novelist Mathias Énard and we’ve come unstuck looking for Goya’s Black Paintings. More might be expected of Énard’s orienteering given he has been wandering the marble halls of the Madrid museum daily for the last six weeks, but one of the traits of time spent with him, whether on a walk, in conversation, or on the page, is never quite knowing where things will lead.

Énard is in his final days as the museum’s writer in residence. When I ask if he has visited other galleries during his time here, he laughs and says, “Yes, I’ve been unfaithful to the Prado.” But he doesn’t mention seeing Guernica at the Reina Sofia, or Rubens’s Venus and Cupid at the Thyssen-Bornemisza. Instead, he talks about the Naval Museum. “If you notice,” he says, “there are no naval paintings here. No sea. How come? That’s a good question. Nothing from the 16th or 17th century, which is the great moment for Spanish navigation. It’s a mystery.”

History – particularly its hidden compartments – and an apparently boundless curiosity fuel Énard’s work. Since 2003, he has published 10 novels, a poetry collection, a graphic novel, and a work of nonfiction. Six of his books have been translated into English (all bar one by Charlotte Mandell), and more are on the way. Zone (2008) was his breakout, winning two major French literary prizes and becoming his English-language debut (it was also the first book to be published by Fitzcarraldo Editions, now one of the UK’s leading indie presses). The novel consists of a single 500-page sentence that plunges us into the mind of a French intelligence agent speeding – both in a train and on amphetamines – through the Italian night, transporting a dossier of atrocities committed in the Mediterranean “zone”.

Violence and conflict are never far off in Énard’s work, in part the legacy of a month spent in Beirut as an embedded journalist writing a story for the French Red Cross in 1991, in the aftermath of Lebanon’s long civil war. We discuss Zone while standing before two large Goyas, The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808 (both 1814): one showing the local inhabitants, or Madrileños, rising up against Napoleon’s occupying army; the other – one of the most stark and impactful depictions of wartime horror – the resulting executions. I tell him that amid current world events the novel feels more relevant than ever. “Sadly,” he agrees. “It’s probably something about human nature. I don’t want to think it’s how humanity functions because that would be too depressing, but actually it’s what the 21st century is showing us. We had this hope, it lasted for 10 or 15 years at the end of the 20th century and the very beginning of the 21st. But now, with the invasion of Ukraine and the disasters of the Middle East, it seems like this is endless.”

This grim turn in the conversation aside, Énard is a delightful companion, a fast and infectious talker who likes to join you in finishing your sentences and often abandons his own before they’re complete. Quick to laugh, he wears his erudition lightly and shares his knowledge with enthusiasm. He was a university lecturer for several years; I imagine a popular one.

Énard was born in Niort, western France, in 1972. While studying art history in Paris he became fascinated with Islamic art. He learned Arabic and Persian and spent several years in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and Iran, studying for a PhD at Tehran’s Shahid Beheshti University. He has written from an Arabic perspective in his novel Street of Thieves, narrated by a Moroccan teenager caught up in the Arab spring, but his most significant work on the relationship between east and west is Compass, which won the Prix Goncourt – France’s Booker – in 2015.

‘All my books are written in French. But I live in another language, so my French is probably contaminated’

‘All my books are written in French. But I live in another language, so my French is probably contaminated’

Like Zone, Compass takes place over the course of a single night, in which an insomniac Austrian musicologist lies in bed touring his memories of working in the Middle East, the interplay of cultural ideas between east and west, and the ways in which the region is mischaracterised, as defined by Edward Said in his 1978 book Orientalism. “That’s orientalism, for example,” Énard says, stopping in front of a 19th-century oil painting, The Moroccan Eavesdroppers by Antonio Muñoz Degrain. “It’s domination of the other, controlling the other’s image.” When I ask him if it’s still prevalent, he replies without hesitation: “Oh yes, it’s still alive.”

Énard has lived in Barcelona for the last 20 years, with two extended spells in Berlin and one in Rome. Given his peripatetic biography, I wonder if he still feels French. “When I write,” he says, “I still write in French. All my books are written in French. That’s my citizenship in the end, you know, the French language. But…” he adds, raising a finger, “I live in another language, so my French is probably contaminated” – he laughs when he uses the word – “by the Spanish environment.” Which is a good thing? “It is a good thing. More freedom with the language. Something… impure, like…” A bastard tongue? “A bastard tongue, yes.”

Related articles:

The Writing the Prado fellowship, which began in 2023 and has brought JM Coetzee, Olga Tokarczuk, Chloe Aridjis, John Banville and Helen Oyeyemi to Madrid, was created in partnership with the Loewe Foundation, the charitable arm of the Spanish fashion house. It gives writers an apartment beside the Prado and the freedom of the museum. Between 9 and 10am they have the galleries to themselves, bustling staff members aside, before the doors open to the public. “So you have this feeling that all this is for yourself,” Énard says. “It’s incredible.” And how does he feel when crowds fill the place? “Totally resentful,” he laughs. “Why are they entering my world?” The fellows’ only responsibilities are to make themselves available for a public event during the fellowship and, afterwards, to write a short story in response to their stay.

I sense a degree of trepidation on Énard’s part regarding this last task. “I don’t write short stories usually,” he says. “It’s a new way of working.” Does he tend to think, then, in terms of larger narratives? “Exactly. When you need more than one idea, and many characters, and now I have to find one idea with maybe a couple of characters, something like that. Something that can be told in – I don’t know – 10,000 words.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Yet the museum is clearly feeding him creatively. “A museum is lots of stories,” he says. “Hundreds of them.” So much of the art surrounding us was created to order: a notion that appeals to Énard. “Of course, I’m not Velázquez or Rubens, but I like the idea of the commission,” he says. It was a commission, in fact, that planted the seed of another of his novels, Tell Them of Battles, Kings and Elephants. He was working on Zone at the French Academy in Rome (another fellowship), and in the afternoons, tired of writing, he would go to the Villa Medici’s library. Picking up Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, he read about Michelangelo receiving an invitation from the sultan in Istanbul. “I read that and I said, ‘What the hell?’”

Vasari doesn’t explain what the commission was for, but in Ascanio Condivi’s biography – “considered to be Michelangelo’s autobiography because he told Condivi what to write, basically” – Énard discovered it was for a bridge to span the Golden Horn. In reality, Michelangelo, who had returned to Florence after falling out with his patron Pope Julius II (a frequent event), considered the invitation but decided accepting would anger the pope. Énard, alive to the currents of history, has his Michelangelo make a different decision, but what I really like is the attention he pays to the invitation’s meaning: the Turks, he says, would never have bothered asking if they didn’t know about the artist’s quarrel with the pope. “I was amazed because this meant the Ottomans knew exactly what was happening in Italy,” he says. “They knew that Michelangelo was free a week after he left Rome.” All that just from taking a book off the shelf, I say. He laughs. “At times you’re lucky.”

Art-blind after a couple of hours, we leave the galleries and have an espresso in the cafeteria, cut across with shafts of winter sunlight. We engage in some literary gossip, which Énard proves to be good at (“writers hate each other, usually”), and he tells me that since coming to the Prado he has been rereading Javier Marías in order “to enjoy Madrid; he really is Madrid”.

Énard hasn’t been writing “because during a residency I usually don’t write, I cannot write. I don’t have time. But you’re getting materials.” When I suggest that might be frustrating, he disagrees. “You know, at the beginning, everything is possible. You say, ‘This is going to be the greatest novel of all time.’” He smiles. “You can dream.”

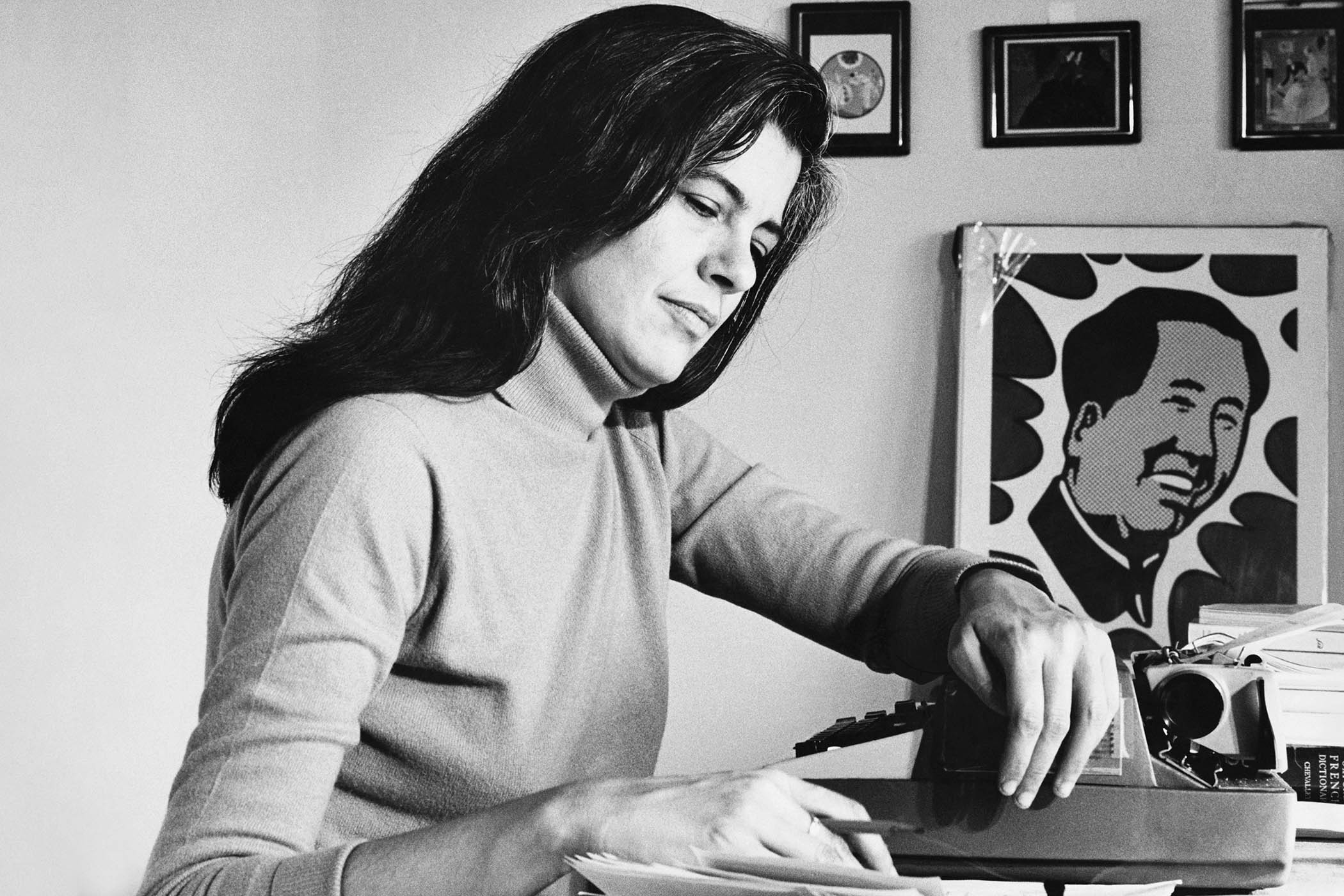

Photograph by Sofia Moro for The Observer