Before dirtying my hands with this dig into centuries of pinching and copying, let me tell you about my own little plagiarism row.

Back in 2013, I wrote for this paper about Kraftwerk, ahead of their residency at London’s Tate Modern. A second piece about the band appeared three days later in another broadsheet: nothing unusual about that, but it included material I’d gleaned for my article from a 1970s magazine in the British Library, which wasn’t online. “I confess I did nick @juderogers reference to Melody Maker’s Kraftwerk review,” the writer responded, to an accusatory friend of mine, on Twitter. “It was too good to resist.”

Fingers flexed, I then waded in, noting that another of his paragraphs was similar to mine. “It’s called sampling,” he joked. “It’s the modern way.” Sampling often requires permission and a fee, I quipped back, linking to a recent ruling by the German supreme court that a hip-hop producer had illegally sampled Kraftwerk. In its write-up of the spat, Private Eye concluded that this was “a riposte so good it’s worth re-using”.

If the farrago proved that plagiarism is a tricky beast, it has only got trickier with the recent arrival of AI-driven technologies such as ChatGPT. Roger Kreuz’s book burrows into the history of plagiarism and its complicated cousin, appropriation, to try to tell us how we got here. A psychology professor at the University of Memphis, Kreuz has written on irony, language and identity, and is interested, the book’s blurb states, in how “language use affects a person’s identity”, as well as “the shifting public attitudes regarding the concepts of plagiarism and appropriation”.

Three decades of spotting student plagiarism also influenced his desire to explore the practice, but he admits in his foreword that he “had bought into some of the myths” such as that “the act is a relatively rare one”. After finding examples by Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winners, high-ranking politicians and bestselling authors, you can almost hear his sighs. “I must confess that this odyssey has dented my faith in human nature.”

Edward Lloyd’s rip-offs of Charles Dickens’ stories included Oliver Twiss and Nickelas Nickelbery

Edward Lloyd’s rip-offs of Charles Dickens’ stories included Oliver Twiss and Nickelas Nickelbery

What follows is a collection of examples from antiquity to the modern day, some more fascinating than others. We leap back to ancient Greece to discover Plato being accused of cribbing from the likes of Protagoras and Moses by philosophers and early Christians respectively. Kreuz identifies the first use of the Latin term plagiario – which originally meant someone who kidnaps slaves or children – in relation to language, in the first century AD. The Roman poet Martial used it to describe a fellow poet who was reciting his work as if it were his own – the “plagiario” was thieving Martial’s literary creations, as if running off with his babies.

We barrel through the eras of Chaucer and Shakespeare, when the rhetorical practice of imitatio was encouraged as a way of praising one’s literary ancestors, then witness Dickens’s disgruntlement as bookseller Edward Lloyd rips off his serialised stories. Their titles are hilariously audacious, including Oliver Twiss and Nickelas Nickelbery.

Strikingly Similar is at its best when it drops big names into juicy plagiarism debates. Kreuz tells of the Canadian journalist Florence Deeks, who spent years pursuing HG Wells through the courts. Deeks was convinced that Wells had used her rejected 1918 manuscript The Web of the World’s Romance – a history of the world, foregrounding the role of women – as the basis of a 400,000-word book he had written in nine months, The Outline of History, published in 1920. Although “Wells had dispensed with her emphasis on women’s place in history”, Deeks spent “many months meticulously documenting the pattern of similarities that she found”, Kreuz writes, even recruiting historians to compare the texts (they reported “in some cases, even the same errors in both”). Wells had been accused of plagiarism previously. But for Wells to have seen Deeks’ manuscript, it must have been sent from Macmillan in Canada to him in England – and, finding no evidence of this, a judge ultimately dismissed the case.

Related articles:

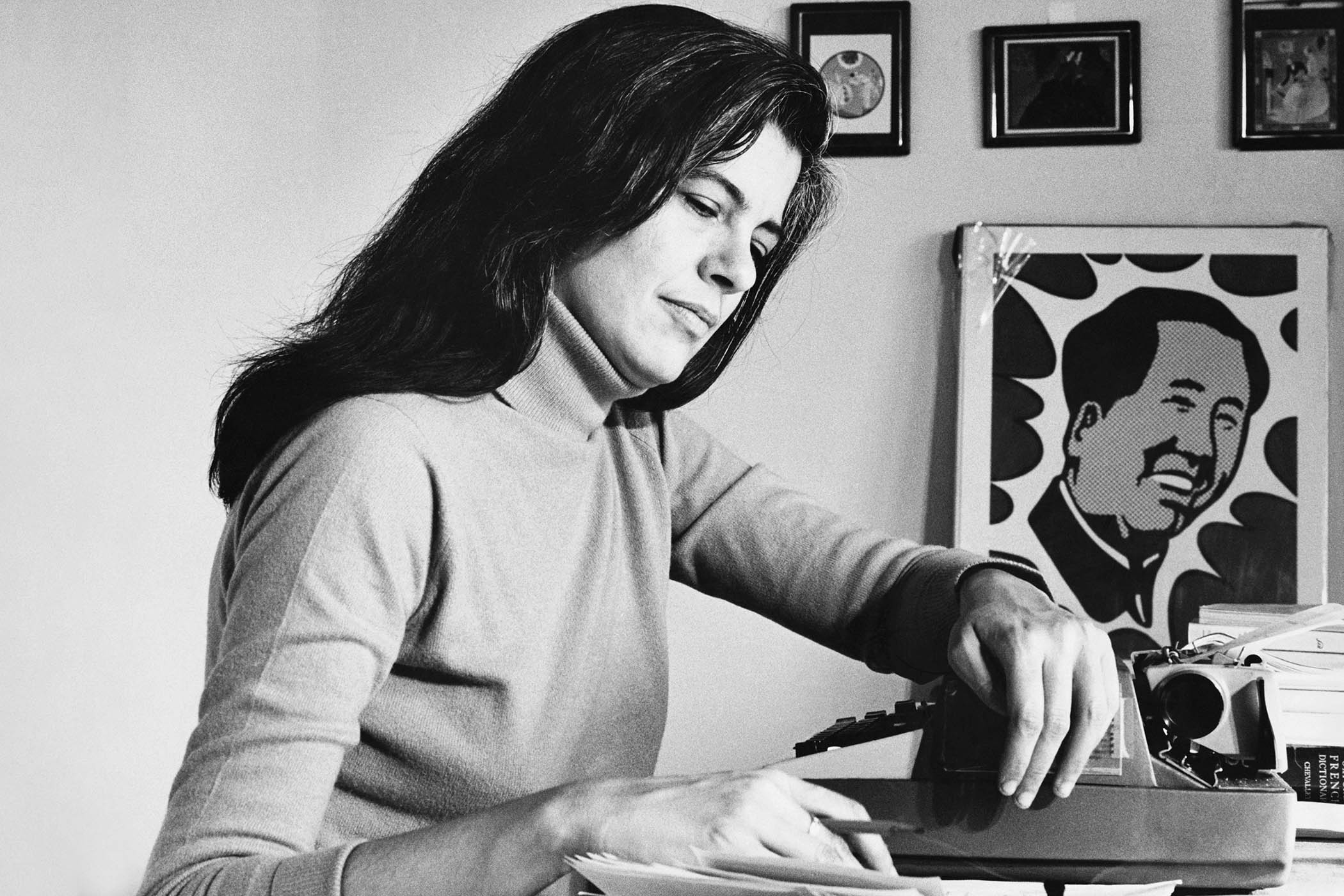

Kreuz includes, too, a defence against allegations of plagiarism by Susan Sontag. Her 1999 novel In America, inspired by the Polish-American actress Helena Modjeska, was found to have incorporated verbatim passages by Willa Cather and Nobel laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz about Modjeska. “I’ve used these sources and I’ve completely transformed them,” Sontag boldly answered her critics. “There’s a larger argument to be made that all of literature is a series of references and allusions.” My favourite accusation of plagiarism lands with another Nobel laureate, Bob Dylan. Passages of his Nobel prize acceptance speech, submitted just in time to secure his prize money, closely resembled a SparkNotes summary of Moby-Dick.

The book is intriguing on the way egocentrism pushes people to pursue plagiarism claims, and Kreuz quotes author David Shields, who in Reality Hunger said that copyright has “obstructed the natural evolution of human creativity, which has always possessed cannibalistic tendencies”. Frustratingly, though, Kreuz doesn’t go much further on the psychology front. He is also strangely toothless on the topic of AI-generated output, arguing that it’s more like ghostwriting than plagiarism, “since there is no ‘original’ that is being copied”. Tell that to writers like me who have had ChatGPT lift phrases directly from their books.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“Bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better,” Kreuz quotes TS Eliot. The good poet “welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn”. As homogenised, machine-made content proliferates, it is this uniqueness that is endangered. Kreuz’s history of plagiarism is instructive, but today the stakes are higher: nothing less than the future of human creativity is under threat.

Strikingly Similar: Plagiarism and Appropriation from Chaucer to Chatbots by Roger Kreuz is published by Cambridge University Press (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph of Susan Sontag by Getty Images