There is something poignant about this wisp of a book – seemingly the last remains of Milan Kundera, novelist, yesterday’s star. It contains one of those dictionaries of most and least favourite words that the cultural lexicographer in Kundera loved compiling and a slight but provocative, moving essay on a Prague he saw disappearing into the “mists of eastern Europe where it never belonged”, both written in the 1980s, his heyday. Kundera’s work was always about disappearance and not belonging. His was the forever exiled writer’s imagination. The essay on Prague –a lament for a culture that no longer exists – ends with a quotation from the Czech surrealist poet Vitêslav Nezval:

Like a piece of paper in flames / Where the poem disappears...

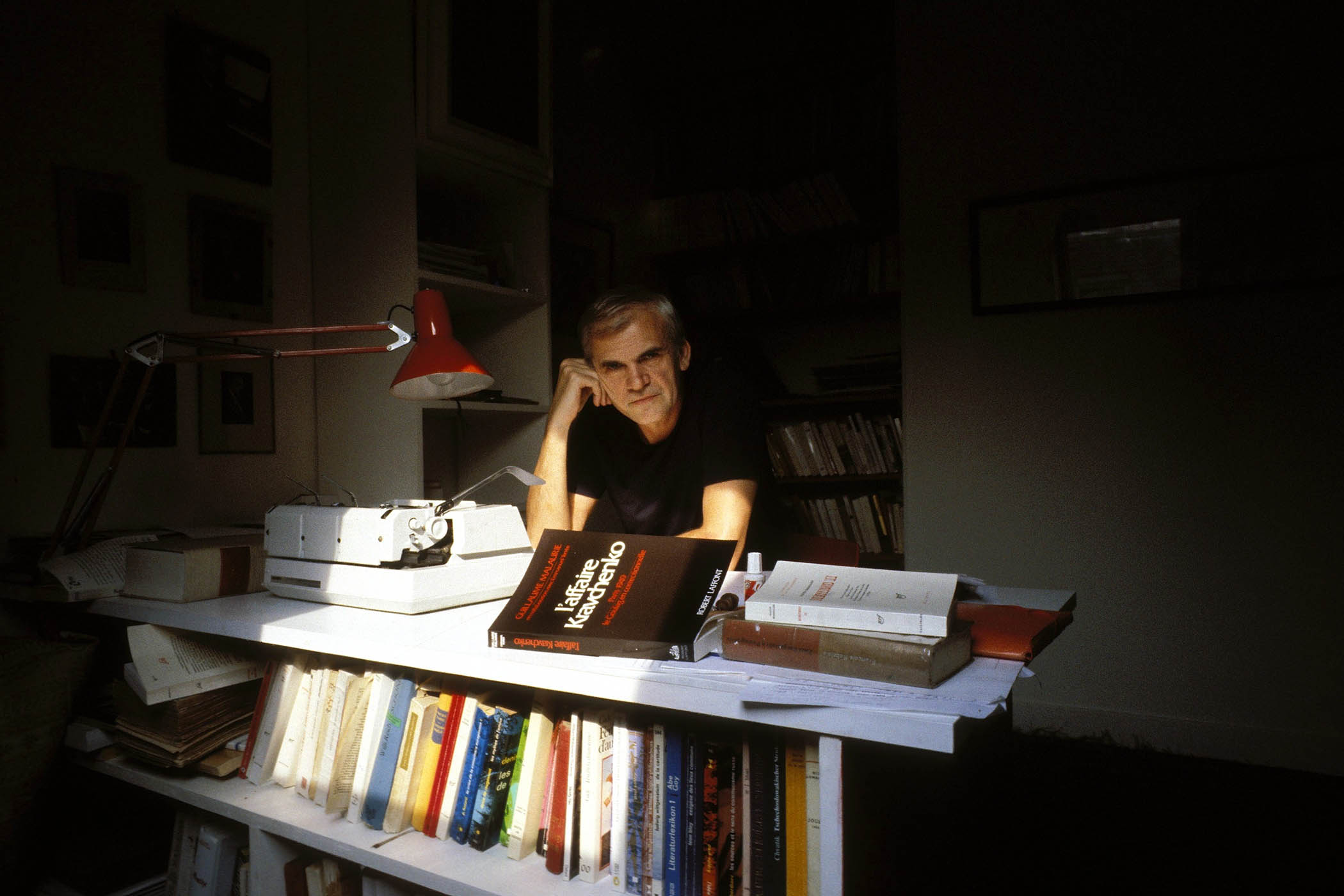

Kundera was cremated himself in Paris in 2023. He was 94. I mean no disrespect when I say it feels as though he died longer ago than that. His work had not gone up in smoke, but he had not been widely regarded for 20 years or more. Fashion for writers changes as does fashion for everything else. I went on revering him though reading him less, but even I could see that the eroticism of his novels, let alone his dictionary definitions on the subject, did not quite ring true or apropos any longer. “Hush, Mr Kundera,” I wanted to say, “we no longer talk about ‘getting hard’ and giving women orgasms in that way. You and Roth! It’s a tact thing. For the moment, at least, masculinism is advised to keep its head down.”

Worse, for his reputation as a hero of resistance to authoritarianism, was a widely circulated rumour that, as a young man in Prague, Kundera had denounced a defector to the secret police. He denied the charge, which was never proved. Novelists such as Nadine Gordimer, JM Coetzee and Salman Rushdie spoke up in his defence, but the damage had been done. The age of censure was upon us.

Writers of Kundera’s unconsoling, non-ideological sort are not much liked at the best of times and a word is all it takes for oversensitive readers to shun them.

Kundera’s speech on receiving the Jerusalem prize in 1985 feels like a testament from another world. What writer careful of his readership today would risk referring to Israel as “the true heart of Europe – a peculiar heart located outside the body” – without invoking settler colonialism? But it’s the spirit that strikes me as alien to our playless times. “We know that the world where the individual is respected (the imaginative world of the novel…) is fragile and perishable,” he warned. “On the horizon stand armies of agelastes watching our every move.” “Agelastes” was what François Rabelais called those who can’t take a joke, those who are deaf to irony and cannot bear disagreement; the conformists and silencers; the certain, the committed, the non-digressors; the innocently lyrical with their bloody smile, who know beforehand what literature should be and what it shouldn’t.

Kundera was always a kaleidoscopic writer, a creator of disjointed scenes that appeared different every time you read them

Kundera was always a kaleidoscopic writer, a creator of disjointed scenes that appeared different every time you read them

One of the strangest, cruellest moments in Kundera’s masterpiece The Book of Laughter and Forgetting – the page falls out of my copy every time I open it – comes when Madame Raphael, an idealistic teacher of foreign students on the Riviera, a woman who had tried but failed to find the dance of ecstatic companionship she longed for in communism and Methodism and the anti-abortion movement and the pro-abortion movement and structuralism and Zen Buddhism and Brechtian theatre, finally gets to form a little circle of innocent rhapsodic gaiety with her students, spiralling up, up and away until they soar laughing above the material earth “like archangels from on high”. The novel has already had a thing or two to say about the laughter of the angels and why the laughter of the devil is to be preferred.

“I too once danced in a ring,” confesses the narrator. I too once – it is a characteristically generous intrusion, an odd alliance with characters he despairs of. “It was the spring of 1948.” A time of verdant hope. One day somebody will write: “I too once marched in a march.” And we will hear the same smart of melancholy disillusion. Word after word in Kundera’s 89-word lexicon returns to the terrible illusion of lyrical unanimity, that search for the one message that will float us out into an eternity of togetherness. “Irony,” Kundera reiterates, “hates messages.”

To read this fleeting collection has consolations akin to going through old love letters. Kundera was always a kaleidoscopic writer, a creator of quick disjointed scenes of love and sorrow that appeared different every time you read them, a coiner of words that pricked and sparkled, went out and then re-formed. You could take him up at an idle moment, put him to your eye and he dazzled. He still does.

89 Words followed by Prague, A Disappearing Poem by Milan Kundera, translated by Matt Reeck, is published by Faber & Faber, (£12.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £11.04. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Francois Lochon/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images