I once asked the legendary Hollywood producer Sam Spiegel what was the greatest challenge of making the epic film Lawrence of Arabia. He replied, “Not getting overwhelmed by the sand.” There’s a similar hazard with Rupert Murdoch. To lumber through the financial minutiae of seven decades of dominance and predation by the world’s most rampant media mastodon is a task better left to biographers who can bear it. The great benefit of Gabriel Sherman’s new book, Bonfire of the Murdochs, is its brevity (256 pages). It allows him to lay bare patterns of ruthlessness repeated over and over again. For Murdoch, Sherman writes, “promises were like inconvenient facts: fungible when they got in the way of profits”.

Sherman adopts a tight focus on the dynastic feud surrounding which of the warring Murdoch kids would control Rupert’s global media empire after his death. An “irrevocable” trust established at the time of his divorce from his second wife, Anna, gave each of them – Liz, Lachlan and James, along with his daughter from his first marriage, Prudence – voting parity. That ultimately jeopardised Murdoch’s plan to solidify his hard-right influence through his media assets, especially Fox News, because only Lachlan shares his paleo-political point of view. But, as we come to see, nothing in Murdoch world is “irrevocable”.

The book opens in September 2024 with the cinematic scene of a convoy of black SUVs, bearing Rupert’s middle-aged heirs, snaking through the Nevada desert “like a funeral procession” to a Reno courthouse, where a judge would determine if the shuffling 93-year-old patriarch could commit his final act of family hurt: blow up the trust, and hand the empire to just one of his children.

Sherman’s competition in telling this story is the hit HBO series Succession, which had so many elements of the real-life narrative that Murdoch’s ex-wife, Jerry Hall, had to agree in their divorce settlement not to help the showrunners with plot points. But Sherman’s Murdoch could not be more different from Succession’s roaring profanity machine, Logan Roy. Murdoch mostly confines bravado to the balance sheet. He is the media world’s great white shark, with a trail of blood at the corner of his thin mouth. He only resembles Logan in that (marvellous) moment in Succession when the fictional patriarch tells his distractible kids, “You are not serious people.”

Rupert is serious people. And his kids? They try. Each is doomed to play out archetypal roles forged by their father’s quest for media dominion: the favourite son, chisel-chinned Lachlan, with the Maga swagger; the prodigal son James, once arty and tortured, now smooth as a recent Stanford business school grad in a Palo Alto pitch; the high-strung dynamo daughter Liz, who, like all female heirs, has had to fight for her place in the power hierarchy; their marginalised half-sister Prudence, who was so devastated when Murdoch didn’t mention her alongside the other three in an interview about his succession that she called her father and screamed down the phone at him. Afterwards he sent her a bunch of flowers “bigger than [a] sofa”.

The legal fight in Reno was the inevitable conclusion of the toxic dynamic that had shaped their four lives. Whatever corporate title Murdoch bestowed on his children was always their measure of how much he loved them. And how much he loved them was always contingent on how well they fulfilled their allotted role.

Sherman’s account of Murdoch’s rise is an exuberant chronicle of seduction and betrayal. Rupert’s superpower, the author suggests, is that he never looks back. He has no guilt and no fear. In business, this allowed him to bet the house and win, time and time again. He has an endless capacity for self-forgiveness and moral expedience.

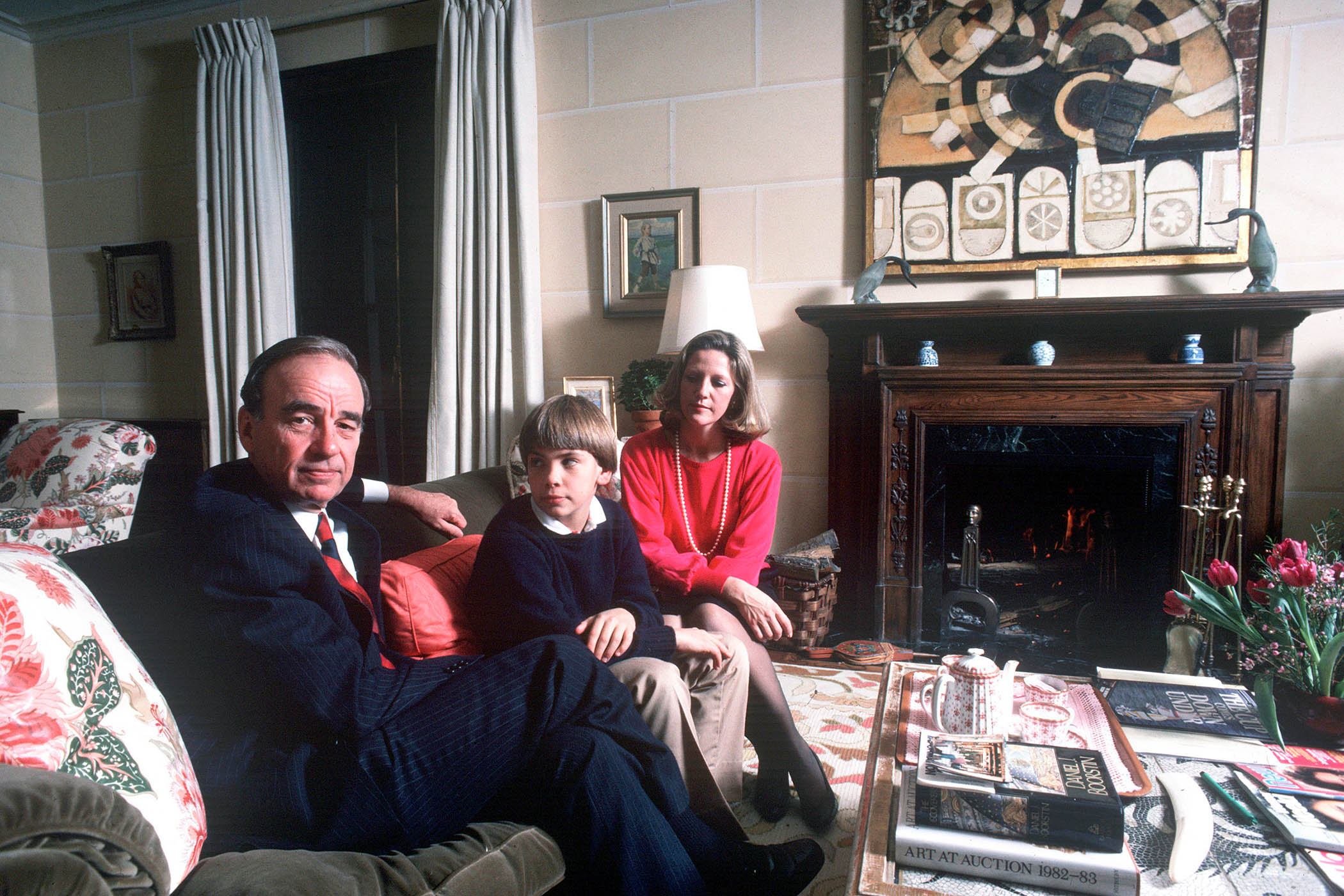

Above: Rupert Murdoch with his children James, Liz and Lachlan in 2007; main picture: Murdoch with his second wife Anna and their son Lachlan, circa 1983.

I saw this up close in the early 1980s, when Murdoch – then known only as a scurrilous tabloid huckster – courted my late husband, Harry Evans, the acclaimed Sunday Times editor, as part of his campaign to acquire Fleet Street’s crown jewels, Times Newspapers, offering solemn pledges to the board to preserve the publications’ editorial independence. (Sherman tells this story with brio and even adds some details I did not know.) He swiftly trashed those promises. Following 13 months of meddling, Rupert fired Harry the morning after the funeral of Harry’s father, right after penning him a sentimental condolence letter about the precious bond of a father and son.

Murdoch had taken the same approach with Clay Felker, the legendary founder of New York magazine. Felker’s mistake was to confide to his pal Rupert that he was having trouble with his magazine’s board. Murdoch promptly went behind his back to buy this prestige asset, then forced Felker out. Felker vowed to fight him “tooth and nail”, to which Murdoch deadpanned in response, “Teeth and nails are fine, but it’s money that wins this kind of scrap.” Harry once said that Murdoch’s middle name should be Macbeth: invite him to dinner, and he murders the host.

It’s impossible not to wonder if there is something Oedipal going on in all the serial patricide, later played out with his own kids in reverse. Sherman has insights.

Murdoch may have written to Harry about the precious bond of a father’s love, but the truth – in Sherman’s version – is that Rupert had a crap relationship with his own. For all his later hagiography about his august father, Australian newspaper magnate Sir Keith Murdoch, his dad had little time for the young Rupert and always treated him as a disappointment. And his mother, the sainted Elisabeth, grande dame of Australian society, was no picnic either. Sherman writes that she taught Rupert to swim as a young boy by tossing him into the pool of a cruise ship. “I had to dog-paddle to the side, and I was screaming,” Rupert has recalled without rancour.

Murdoch had his own Darwinian filial moment when, in 2000, he installed the callow 29-year-old princeling Lachlan as deputy COO of News Corp, throwing him into the cage fight of corporate politics. Lachlan was soon eaten alive by Fox News tyrant Roger Ailes (who, Sherman writes, spread fake rumours that Lachlan was gay) and News Corp COO Peter Chernin. “It wasn’t the most emotionally intelligent way for Dad to handle it,” Liz told journalist Sarah Ellison. “He doesn’t really have the tools to say he’s sorry.”

It’s a wonder all three of the Murdoch kids are not in a psych ward

It’s a wonder all three of the Murdoch kids are not in a psych ward

He wasn’t sorry. Rupert seemed not to wonder why the only times his kids prospered were when they were out of his oversight: Lachlan in Sydney, where he set up his own investment firm (he notched some failures but also some highly lucrative wins); James in Hong Kong, for a successful run as CEO of Rupert’s Star TV; Liz in London, building her production company Shine that cranked out hits like MasterChef. Heady with her independent achievement, she was thrilled by the validation from her father when News Corp bought Shine for £415m. It was also a trap. Sherman reports that Rupert had promised her a seat on the News Corp board and told her that she was his preferred successor. Once she signed the deal, he stopped talking to her. “She was heartbroken,” a friend recalled.

Rupert’s approach to parenting was carnivorous – overpromote the kids and blame them when they failed. At the end of 2007, just as James was proving himself an able CEO of BSkyB, Murdoch elevated him to the role of chairman as well as overseeing News Corp’s businesses in Europe and Asia. That put James in charge of all his father’s British newspaper titles, even though he had no affinity for the world of print. It also meant James was at the helm in London when the News of the World phone-hacking scandal broke. The revelation that breaking into voicemails – not only of royal and celebrity phones but also of crime victims – had been carried out on an industrial scale, and then covered up at the highest level, was to prove an existential corporate crisis. No one was less equipped to be drowned in the sewage of tabloid corruption than squeaky-clean James Murdoch, with his MBA-speak and liberal sensitivities.

As the company imploded, James persuaded his pridefully combative father to close his beloved News of the World. Sherman tells us that Murdoch never forgave James for cornering him into this panicky move. In a hideous Hunger Games-like scene, Murdoch instructed Liz to walk down the hall and fire her brother. She did, and the siblings didn’t speak for years. Sherman reports that Liz later said, “It’s one of the greatest regrets of my life.”

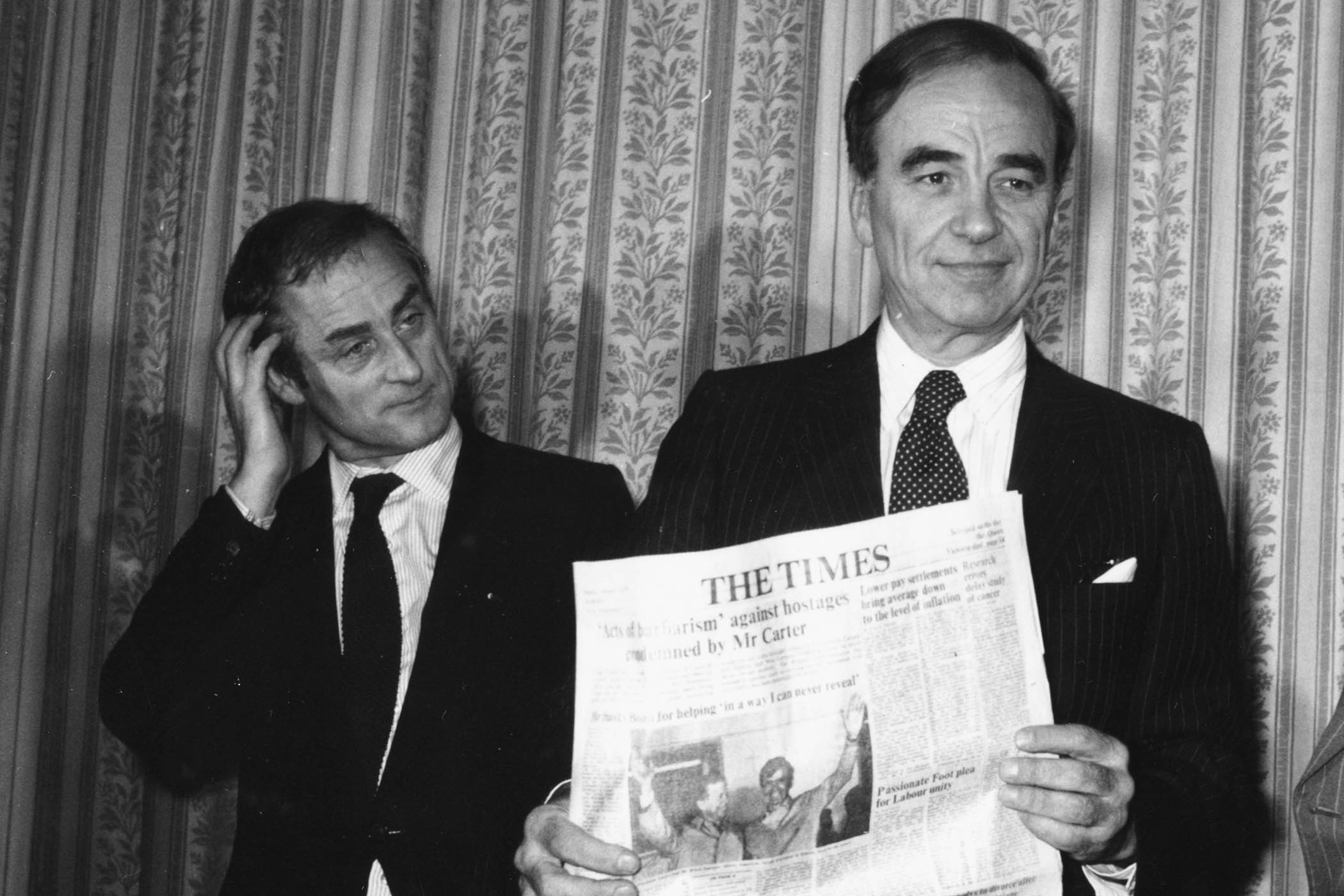

Murdoch (right) with Harold Evans in 1981, after he took ownership of Times Newspapers.

Jesus Christ. It’s a wonder all three of the Murdoch kids are not in a psych ward. And we haven’t even talked about their father’s marriages. Rupert left his starter wife, Patricia, whom Dame Elisabeth always considered downmarket, for the ladylike beauty Anna Torv, mother of Liz, Lachlan and James. After 32 years of white-toast marriage, it was assumed Anna was a keeper. But then we enter what I think of as Rupert’s Viagra era.

His friends were stunned when, in 1999, and at the age of 68, the gnarly old gargoyle Murdoch divorced Anna and married 30-year-old Wendi Deng, the hot, go-getting Chinese-born Star TV employee who caught his eye in Hong Kong. Despite the iconic act of devotion when she smacked the man who launched a shaving-cream pie at Murdoch during a phone-hacking hearing, he shed Wendi after 14 years (and two daughters) because of rumours – likely spread by Roger Ailes – of infidelity. (Wendi told me she was first aware she was being divorced when her phone started to blow up while watching a school play at Spence in New York.)

On to wife number four: Mick Jagger’s ex, Jerry Hall. It was reasonable to expect the marriage to end with the still glamorous Jerry as a widow, not a divorcee. But, in 2022 and after six years, she, too, was fired from the marital bed, this time in a terse email that concluded, “My New York lawyer will be contacting yours immediately.” And yes, there is a wife number five: the low-key but well-connected Russian former scientist Elena Zhukova, who was 67 to Rupert’s 93 when they married in June 2024.

With all this marital mayhem, it was lucky that the dynastic interests of the three kids by Anna were intact in the “irrevocable” trust, right? Wrong. After all the years jockeying to run his empire, Murdoch’s last epic deal sold it out from under them. Offloading 21st Century Fox to Disney for the eyewatering, top-of-the-market price of $71bn in 2019, just before the streaming wars began, was classic Rupert strategic brilliance. As always, the kids were played off against each other. James favoured the deal because he thought it meant escape from his father in the guise of a big leadership role at Disney. (Not happenin’.) Lachlan, meanwhile, was castrated, his great prospects now a rump news company, albeit dominated by the profit-gushing Trumpian mouthpiece Fox News. Everyone knew that James and Liz despised Fox and itched to exercise their voting rights to ditch it to the highest bidder as soon as Rupert died.

Which brings us back to that courthouse in Reno. Is anyone surprised that the great white shark prevailed once again, winning the right to exercise his will beyond the grave and install Lachlan as his corporate heir? This time, betting the house meant the disintegration of the Murdoch family. But it’s hard to shed tears. Whatever their moral posturing about Fox News, the other Murdoch children enjoyed its spoils; their price to walk away was $1.1bn apiece. “Lachlan got the kingdom,” Sherman writes, “James, Liz, and Pru got their freedom,” and Rupert “was still in the game.”

The only tears to be shed are for the rest of us, who have seen how Fox’s degradation of truth created the monstrous phenomenon of Donald Trump and stoked the partisan hatred that has split America. In seven decades of despoilment, it’s the steepest price yet paid for Murdoch’s pathology of power.

Tina Brown is author of the Substack Fresh Hell

Bonfire of the Murdochs: How the Epic Fight to Control the Last Great Media Dynasty Broke a Family – and the World by Gabriel Sherman is published by Simon & Schuster (£25)

Photography by Peter Carrette Archive/Getty Images; Tom Stoddart/Getty Images; Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy