In December 1928, a group of eminent literary figures met for dinner at a London private members’ club to thrash out the basis for a new type of book organisation. What would follow over the next 40 years, as Nicola Wilson describes in Recommended!, her enormously engaging history of this “quiet revolution”, would be thousands of recommendations and hardback first editions for paying readers.

The Book Society, hosted initially by the bestselling novelist and screenwriter Hugh Walpole, who put together the first selection committee and remained energetically involved until his death in 1941, provided something unheard of in the UK at the time: a book subscription service in partnership with publishers that any member of the public – should they be able to stump up the cost each month – could join. Although such associations already operated in France, Germany and the US, British readers were reliant on circulating libraries such as Harrods or Mudie’s for the wealthier, WH Smith and Boots’ lending libraries for the middle classes, and the public library or working-men’s institutes for everyone else.

Crucially, the British were at this point – for reasons of habit, affordability and supply – a nation of book borrowers, not book buyers. Much of this was to do with price and accessibility – it was some years before Allen Lane would produce the first paperback book at Penguin in 1935. “There is a deep-rooted idea in the ordinary English mind that it is extravagant and wrong to own books,” wrote HG Wells in 1927. This new club was adept at consumer marketing: early adverts promoted the Book Society as “an aid to the busy reader” with a monthly recommended choice which could be exchanged for an alternative title from one of its main categories: fiction, nonfiction, history, memoir and travel. Just as the internet behemoth Amazon would, some 70 years later, quickly become essential for publishers, the society, with its large numbers of pre-orders, enabled the industry to increase print runs, find new customers and create bestsellers.

Society hostess, poet and critic Sylvia Lynd.

For Wilson, an academic who co-directs the Centre for Book Cultures and Publishing at the University of Reading, Recommended! is abundantly a labour of love as well as one of professional interest. It is a pity, then, that the book is riddled with errors such as “The Forsythe Saga” replacing The Forsyte Saga and, most implausibly, Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (who died in 1889) as the translator of 1939’s Verdun, by Jules Romains. (The actual translator of the book is plain Gerard Hopkins.) Wilson first came across the Book Society in the archives of the Hogarth Press, set up by Leonard and Virginia Woolf, perhaps as far from populist publishing as could be at the time – though Woolf’s Flush was a 1933 Book Society choice, and she and Walpole were friends.

Wilson’s take is that the Book Society, whose own records were sporadically kept, was the Richard and Judy, Oprah or BookTok of its time, and it is certainly a forerunner of the more niche Folio Society (set up in 1947, one if its co-founders being Book Society committee member Alan Bott), and the later, resolutely commercial mail-order book clubs such as BCA (Book Club Associates). But the Book Society, with its opulent headquarters and members’ room, its exclusive bookplates and newsletter, was something different.

That bricks-and-mortar members’ room is a far cry from our digital age, with current book experts and sharers including any number of podcasters, Instagrammers, YouTubers, Substack users, plus Dua Lipa’s immensely popular Service95 monthly book club. Compellingly, Wilson tells its story through the larger-than-life characters who moulded it. Walpole, himself a “literary celebrity”, churned out a bestselling novel a year, most of which are now forgotten, though his speaking tours of the US could rival those of Dickens in terms of scope and tiring itineraries. Walpole was famously satirised as a talentless popular novelist by W Somerset Maugham in 1930’s Cakes and Ale, a “clever piece of torture” as Virginia Woolf put it. He was homosexual – illegal at the time – and his lover, Harold Cheevers, acted as his chauffeur. Cheevers himself was married to a woman with children, and Walpole became an accepted part of their family. Cheevers’ calm devotion to the nervy and ebullient Walpole is touchingly portrayed throughout. (What Cheevers’s wife, Ethel, thought about the arrangement is not recorded).

After Clemence Danes left for Hollywood, Sylvia Lynd was the sole woman on the committee, and better known as a society hostess, her Hampstead soirees a world away from the snobbier Bloomsbury. Lynd came from a highly politicised Anglo-Irish family and was married to an Irish nationalist and journalist. When James Joyce and his partner Nora finally married, after 27 years together, on 4 July 1931, the Lynds hosted the celebrations. Sylvia, a poet of rather limpid expressiveness, was, however, an excellent critic, and tempered the frequent fallings out of Edmund Blunden – the Oxford academic, poet and first world war veteran – and the poet and one-time communist Cecil Day-Lewis, father of actor Daniel.

Blunden, who tried to suppress Robert Graves’s I, Claudius as a Book Society choice because he disapproved of Graves’s Goodbye to All That (a rival to Blunden’s own first world war memoir Undertones of War), had as complicated a love life as the younger Day-Lewis, which Wilson enjoyably dissects here. Blunden’s fretful, uneasy diaries and his public and unwavering support of appeasement would eventually bring him to the attention of the authorities as “non-patriotic”.

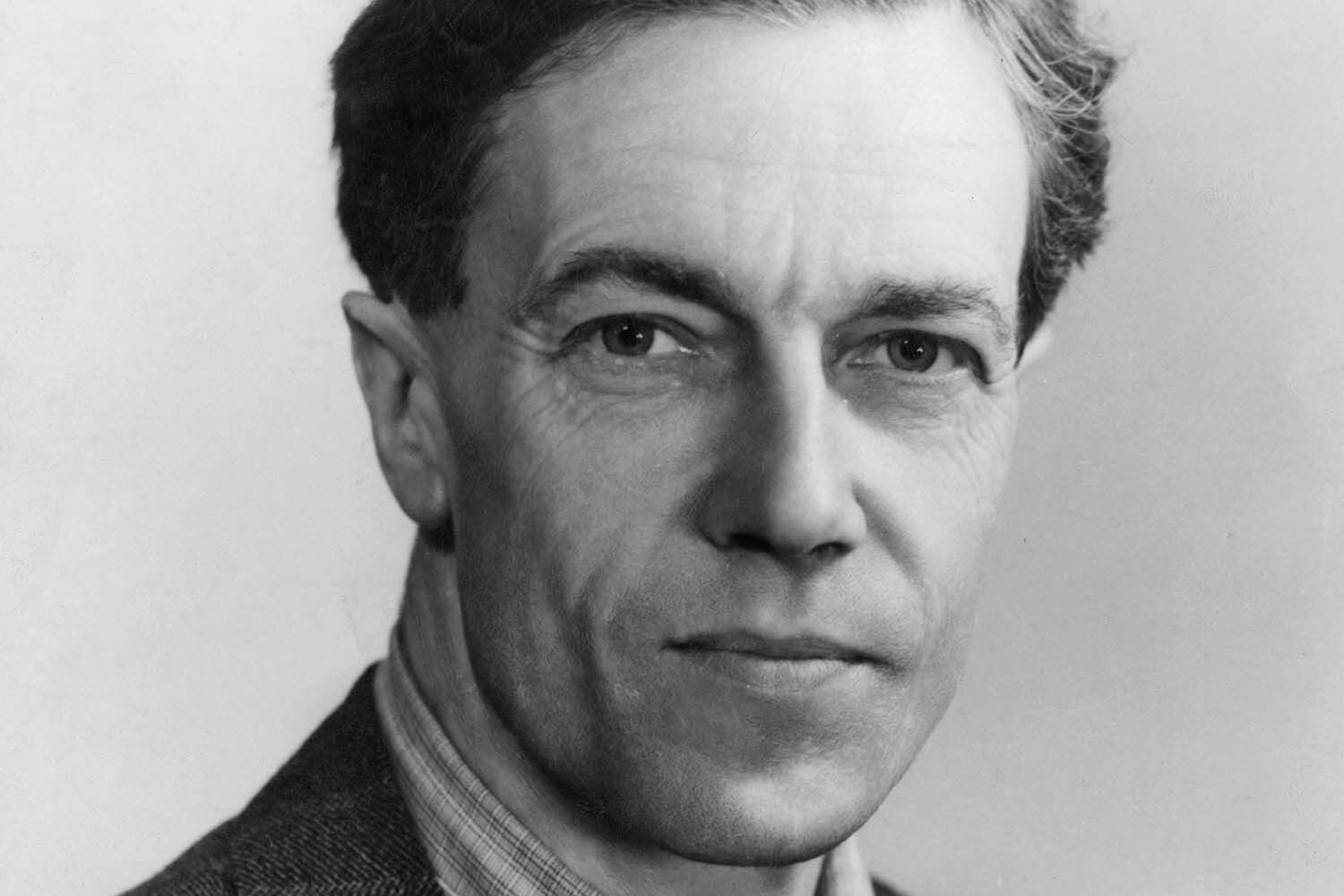

Cecil Day-Lewis, who shared a rivalry with Edmund Blunden.

The second world war is the meat of the book: Wilson charts the individual tribulations of the group; the sharp decline of paper supply, rationed for the war effort; the blitz and its effect on London’s book trade. On 29 December 1940, in Paternoster Row, next to St Paul’s Cathedral, the offices of the Bookseller, 17 publishers and the UK’s largest book wholesaler were flattened. The Bookseller later commented that “basements full of stock” were “now the crematories of the City’s book world”.

Day-Lewis, meanwhile, married with two sons, was then living with the celebrated novelist Rosamond Lehmann, a Book Society “double whammy” (a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic). Day-Lewis worked at the publishing arm of the Ministry of Information during the war, which subtly influenced Book Society choices during those years: historical novels and derring-do page-turners alternating with, for example, a volume of Churchill’s speeches.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

After Walpole died suddenly in 1941, (leaving behind a huge library and art collection), JB “Jack” Priestley, an early committee member and soon to write what became the postwar play, An Inspector Calls (1945), would bring new, acerbic life to the society. Wilson wraps up its final 20 years briskly, as for her (and us) the most interesting part is over. The rise of the cheap paperback would eventually do for the Book Society; its last publication was Iris Murdoch’s The Nice and the Good, in 1968. Wilson provides a register of Book Society choices over the decades, listing writers now obscure and many more rescued from oblivion in later decades (particularly in terms of women writers by Virago and Persephone presses), the perfect complement to this fascinating, gossipy and well-researched slice of publishing history.

Recommended!: The Influencers Who Changed How We Read by Nicola Wilson is published by Holland House Books (£15.99). Order a copy from observershop.co.uk to receive a 10% discount. Delivery charges may apply.

Photographs by Bridgeman/Getty