There are two sorts of articles that tend to be written about the decline of public libraries in Britain. The first laments the effect of austerity on these vital civic institutions: when libraries go, they take literacy, education and community down with them. The second makes the opposite case – that libraries are no longer needed. The numbers of loaning books have been falling for decades, long before austerity. The real culprit is not scarcity, but abundance: the internet, cheaper books and smartphones.

Let’s start with the facts. Libraries are in trouble. More than 180 of them have closed or been handed over to volunteer groups since 2016, and the most deprived areas were four times as likely to lose a library than the richest. A third of those remaining have had their hours reduced. The amount spent on libraries fell by almost half in real terms between 2009-10 and 2022-23.

Part of the problem, according to Richard Ovenden, Bodley’s librarian at Oxford University, is that the responsibility for libraries is ambiguous. While the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) is nominally in charge of improving them, devolution has meant the burden for doing so falls almost entirely on stretched local councils, who must provide the lion’s share of the funding. Those who campaign to save these institutions must compete with advocates for children with additional needs, the elderly and fixing potholes. Why should libraries absorb this money?

A solid case for libraries can nevertheless be made, according to Nick Poole, the former CEO of the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. Once they were vital for spreading information; now we need them to help us wade through it. “What I see is a society that has gone digital without knowing what that means,” he says. If you were trying to design the perfect antidote to misinformation, you could do worse, he says, than a “network of trusted safe places with secure internet connections and people who were dedicated from a civic point of view to helping you navigate this world”.

Combating this global problem sounds like an overly grand project for a down-at-heel local library. But Poole suggests two way these institutions might help. One is to start curating bodies of trusted knowledge themselves; the other is to provide lessons, training people in media literacy. But that requires investment too. “About 15 years ago there was a big push to train librarians in those skills. That hasn’t been kept up,” says Poole.

Even so, many libraries are already helping people with digital skills at a more basic level. One of the busiest days in libraries tends to be 7 January. Why? People come in to get help switching on/setting up new phones, kindles or laptops, or downloading books on them. Doctors routinely send people to local libraries to help them look at their patient data.

Once they were vital for spreading information; now we need them to help us wade through it

Once they were vital for spreading information; now we need them to help us wade through it

Isobel Hunter, CEO of Libraries Connected, says any strong argument for libraries must focus on vulnerable people, and the ways in which they can supplement other expensive forms of support.

“Older people can be helped to be more self-sufficient,” she says, “booking prescriptions and having online doctors meetings. It may reduce the need for adult social care.” There is plenty of evidence, too, that “digital exclusion” harms children – a library can help combat this. Research shows early “literacy interventions” may save £830m per school year group by boosting education and reducing future social costs. “When we reopened over lockdown, a person was queuing outside the library crying, saying he had to apply for a job and hadn’t been able to. Others use libraries to apply for benefits,” says Hunter. Suffolk Libraries Service found an £8 “social return on investment” for every £1 of taxpayer money spent on the service – a measure which looks at everything from mental health to children’s literacy to happiness.

A surprising number of businesses have been started in libraries, says Poole – a simple effect of free bookable meeting rooms and a stable internet connection. They are twice as likely to succeed and continue trading after three years as businesses started elsewhere – an effect of lowering costs of entry. Business owners who began in libraries tend to be more diverse: between 2020 and 2023, 72% were women, 26% from ethnic minorities, and 12% from deprived areas. Studies have also found a “halo effect” of libraries on local businesses (they increase footfall), and house prices (libraries signal a thriving community).

Some areas are bucking the trend. Manchester and Doncaster have invested in their libraries, and this has been rewarded with a rise in book borrowing. Then too, plenty of people are still getting a lot from their libraries: 30% of adults in England have used a library at least once in the past 12 months.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But the case is still hard to make, especially to councils in deprived areas where money is tightest and need is greatest. Once cuts start, the quality of provision declines, and fewer people visit. Star authors such as Philip Pullman, Kate Mosse and Richard Osman have launched a campaign to issue every newborn with a library card. The scheme would mean the creation of a “National Library Card” that would give every UK citizen access to libraries and weave the library into everyone’s daily life.

The catch is it could cost up to £22m, and many local libraries are unlikely to be able take it much further. One idea might be for central government to take more responsibility for libraries – and provide more of the funding. “A tiny bit of Arts Council funding goes to libraries,” says Ovenden. “They could do a lot more.” Literacy may be better as a national project than a local one.

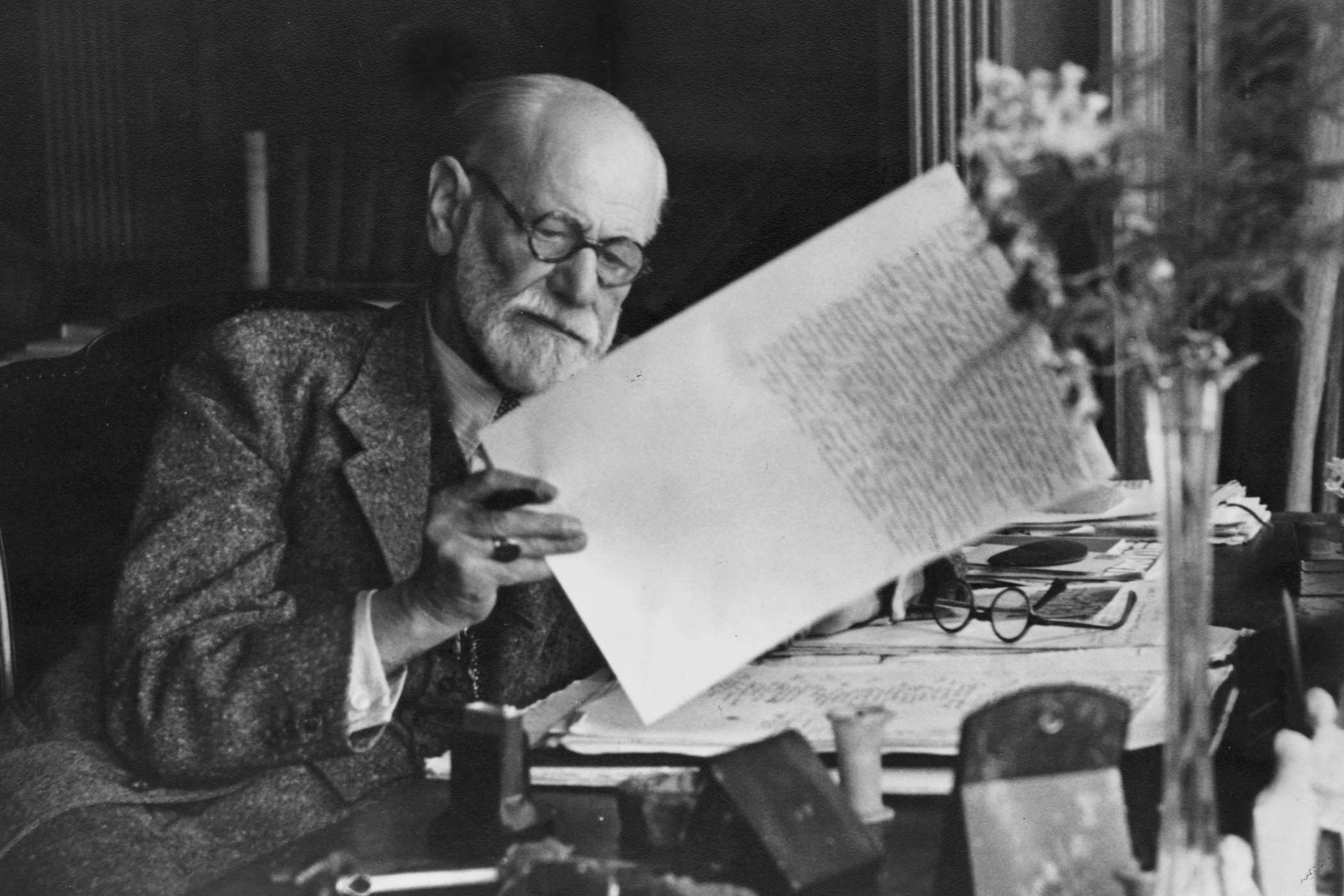

Photograph by Alamy