The passengers and crew on El Al flight 426, returning to Tel Aviv from Rome on 23 July 1968, probably did not realise they were on a history-making flight, even after it was forced to land in Algiers by men armed with pistols and grenades. Planes were hijacked with surprising frequency in the 1960s, especially in the United States, as an illicit means of transportation (often to Cuba) or as a pretext for extortion.

This case was different. The hijackers were fedayeen (commandos) from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a Marxist-Leninist group based in Jordan. The PFLP negotiated with the Israeli government for the release of Palestinians in Israeli jails in return for the plane, crew and 12 Israeli passengers. This was not only the first of a long line of terrorist aircraft hijackings, but also, as Jason Burke points out in his absorbing history of terrorism in Europe and the Middle East from 1967 to 1983, Israel’s first direct negotiation with a Palestinian group. There would be many such negotiations in the decades to come.

The PFLP and other Palestinian groups recognised not only that aircraft hijackings were relatively easy – Burke’s book contains several accounts of sometimes heavily armed militants easily bypassing airport security measures – but that they were a way of exporting the Palestinian issue away from the Middle East. Hijacked aircraft were perfect vehicles for commanding attention in the new media economy. Burke quotes Brian Jenkins of the Rand Corporation thinktank from 1975: “Terrorists want a lot of people watching, not a lot of people dead.”

It was in this period that terrorism became global – and spectacular, with images and drama designed for television. Nothing captures this more powerfully than the events of September 1970 when the PFLP hijacked five aircraft, forcing three to land at Dawson’s Field, a former Royal Air Force base in Jordan. A Boeing 747 was diverted to Beirut and then Cairo, as it was too large for the Dawson’s Field landing strip, while the hijackers on an El Al flight, including the infamous Leila Khaled, were overpowered and the aircraft was piloted to Heathrow.

In September 1970 PFLP gunmen hijacked 3 passenger jet airliners and diverted them to Dawson Field, remote desert airfield near Amman Jordan

With the planes came American, German, Swiss and British hostages, and for a few days this dusty airstrip became the centre of global negotiations, as Israeli prime minister Golda Meir, King Hussein of Jordan, US president Richard Nixon and British prime minister Edward Heath argued over the merits of negotiation and concessions or a military response.

Hussein’s conclusion – that the armed Palestinian groups needed to be removed from his kingdom by force – would have momentous regional consequences, but the crisis would also live on in the footage, captured by two journalists who were invited on to the airstrip by the PFLP, of the simultaneous explosions that destroyed all but the tailfins of the three evacuated aircraft. When, two years later, fedayeen linked to Yasser Arafat’s Fatah planned an even more attention-grabbing operation, they chose the Munich Olympics – targeting Israeli athletes at what would be the most extensively televised event in world history.

Leftwing terrorism of the 1970s gave way to the religious terrorism that is still with us today

Leftwing terrorism of the 1970s gave way to the religious terrorism that is still with us today

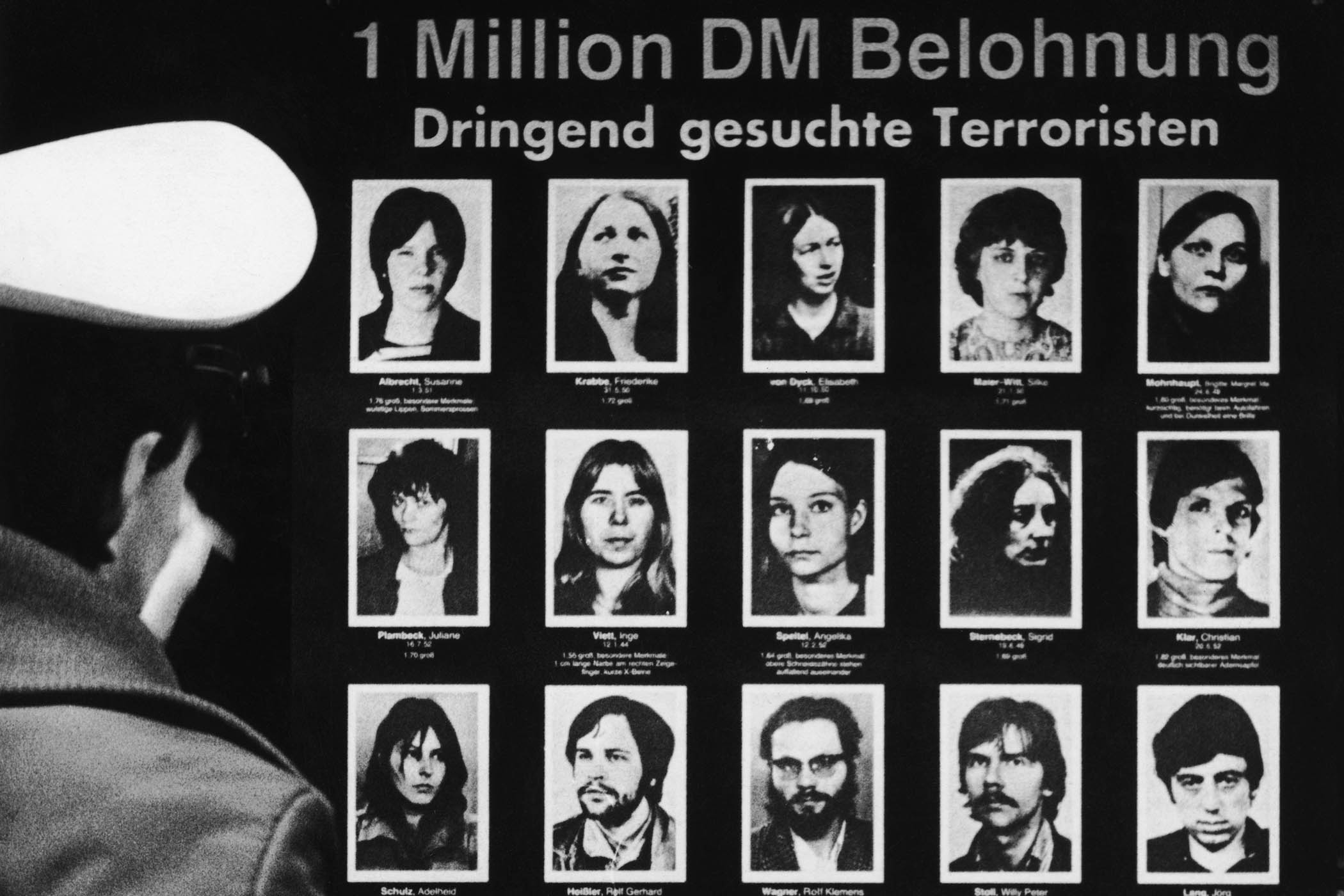

After 1967, extreme leftwing movements across the west began to make common cause with the Palestinian groups, and several hundred European volunteers attended a Fatah camp in Jordan in 1969-70, including the leaders of West Germany’s Red Army Faction (also known as the Baader–Meinhof Gang): the irascible and narcissistic Andreas Baader, the group’s theoretician Gudrun Ensslin and Ulrike Meinhof, a prominent activist journalist.

Related articles:

This became more of a clash of cultures than a case study in militant cooperation, as the West Germans insisted on sleeping together and sunbathing topless while complaining about the physical rigours of their training, to the exasperation of their Palestinian hosts. Burke perceptively judges the violence of the Red Army Faction to be more performative than instrumental, in contrast with the practical and determinedly political Palestinian groups it admired, but its performances nonetheless succeeded in capturing the world’s attention.

Its final acts, at Stammheim prison near Stuttgart, were tragic. Meinhof hanged herself in 1976, and the following year, two terrorist operations were mounted aimed in part at securing Baader and Ensslin’s release, one of which was the hijacking (by a PFLP splinter group) of Lufthansa flight 181 to Frankfurt in October 1977. Burke’s account of this saga is particularly gripping: the plane was forced to land in Rome, Larnaca in Cyprus, Dubai and then Aden, where the captain brought the plane down on sand and gravel as the runway had been blocked to prevent its landing. The hijackers nonetheless murdered the heroic captain and forced the remaining crew to pilot the aircraft and its traumatised passengers – who were strapped to their seats and forbidden from using the bathrooms – to Mogadishu. There, a German special forces operation of astonishing skill succeeded in killing or apprehending all the hijackers and liberating the hostages. As soon as Baader and Ensslin and another militant learned of the failure of the hijacking, they killed themselves.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The Revolutionists, which has been shortlisted for this year’s Baillie Gifford prize, is at its strongest with these intertwined stories of Palestinian and European militancy, which show how mass media enabled terrorism to become a way of doing politics by other means. It brings to life the terrorist celebrities of the 1970s such as Meinhof, Khaled and the Venezuelan Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, who, as Carlos the Jackal, was simultaneously a creation of newspaper editors and a remorselessly effective gun for hire. Burke then shows how the wave of leftwing terrorism that crested in the mid-1970s swiftly gave way to the religious terrorism that remains with us today.

The omens of this new terrorism in the Middle East were mostly missed until 1979, when the Shia Muslim world was changed by revolution in Iran and the seizure of the Great Mosque in Mecca by a millenarian sect revealed one of the violent undercurrents in Sunni Islamism. The popular support for the Iranian revolution showed religion, at least in the Middle East, to be a more powerful revolutionary force than Marxism, although the Ayatollah’s regime took no chances with the leftwing groups that supported the revolution, such as the Mujahedin e-Khalq, whose mixture of Marxist-Leninism and Islamism was enormously popular – and so the group was ruthlessly purged.

Above: Layla Khaled photographed in 1969 after the PFLP hijacking of TWA flight 840; main picture: two of the passenger jets that were diverted by the PFLP to Dawson’s Field in Jordan, September 1970.

Given that Burke has written authoritatively on jihadism in previous books, the chapters in The Revolutionists that narrate the rise of Sunni Islamism in Egypt and Saudi Arabia and its evolution in Pakistan and Afghanistan into a global threat are more familiar and less compelling. Instead of another telling of this well-known story, I would have liked to read more about the other leftwing groups that terrorised Europe in the 1970s such as the Red Brigades, which kidnapped and murdered the Italian prime minister Aldo Moro in 1978. But this is a minor criticism of a deeply researched, ambitious and elegantly written book.

In the 1970s, terrorists were after viewers rather than victims. But while our attention was fixed on Dawson’s Field, Munich and Stammheim prison, a new kind of violence was in the making. This would combine the spectacle of 1970s political terrorism with a cosmic vision of moral revolution – a vision that would ultimately lead to the horrors of 9/11, the Islamic State and 7 October 2023.

The Revolutionists: The Story of the Extremists Who Hijacked the 1970s by Jason Burke is published by Bodley Head (£30). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £27. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Nik Wheeler/Getty Images, Bettmann Archive/Getty Images