Entitled, the story of the Duke and Duchess of York, is a soup of sycophancy and spite. The sycophancy is for what they are – royal, and the wisdom of this system is never questioned, even as the author, consciously or not, assembles the case for the guillotine. The spite is for who they are, which is a pair of cracked grifters who have less shared self-awareness than the corgi Sarah reportedly thinks is a reincarnation of Elizabeth II. Both Yorks emerge from Entitled as mad, but, as ever, we – the gawpers and enablers – are the more insane. And so, when dealing with this 400-page gossip column, we must open with the sympathetic line: the emotional deprivation of their class, last detailed in Prince Harry’s Spare, which remains both the best book on the royals, and the reason they will never forgive him for writing it. It would be the only human thing to do, and there isn’t much humanity around.

Andrew Lownie, with little supporting evidence, claims the Yorks’ parents slept together. Not Elizabeth II and Ron Ferguson, a major who galloped through massage parlours, but Prince Philip and Susan Barrantes, Sarah’s mother, who left the appalling Ferguson for a polo player with whom she was sexually obsessed. There is so much inappropriate – and worse – sex here, and so much hunger. It is, in this telling, how the Yorks communicate, with sex and ugly consumer goods, and with need. This is how insatiability ends.

Lownie, a literary agent and biographer of the Mountbattens and Guy Burgess, details how, abandoned by her mother, Sarah became a compulsive eater and dieter, spender and earner, and chaser of bad men. (Eventually bad men became fantasy men; she apparently coveted John F Kennedy Jr, Kevin Costner and Tiger Woods, among others). Sarah’s cheerfulness was a feint, and she married Andrew on the rebound from Paddy McNally, a man who would by Lownie’s account bring girls back to the chalet and offer her a threesome or the spare room. The proposal came after a snowball fight in Scotland – violence posing as fun, the aristocracy in snow. They met as infants, they married as them, they remained them.

Contrary to their self-image, which is all victimhood, the Yorks are studies in corruption

Contrary to their self-image, which is all victimhood, the Yorks are studies in corruption

Andrew is a Peter Pan, a child who once rode his tricycle through Buckingham Palace, like the boy from The Shining, and never grew up (he still claps at The Muppets, Lownie reports). He was gifted the weird legacy of being Elizabeth II’s favourite, and therefore worst, child. He is a bully, a friend to sex traffickers – he maintains he did not know they were sex traffickers. Lownie offers an explanation for this: he quotes a source saying Andrew lost his virginity – his innocence – at 11 to a prostitute hired by a friend’s father, which, if true, may offer a psychology for the prince’s compulsive using of women, his lifelong insomnia (the frightened don’t sleep) and his occasional fury, which emerges in small and pointless acts of violence. Lownie says Andrew once drove his Range Rover into gates in Windsor Great Park, and reports the hearsay that he once pushed a woman’s face into her food. Andrew has the sympathy for himself common to all Elizabeth II’s sons: he sometimes signs visitor books “Frog”, as if a kiss would save him. It didn’t: the opposite was true, because sex, as we all know, felled him. For leisure, he takes photographs of sheep in distress: does he identify with them? He told David Frost his essential theme was “loneliness” and told another journalist he would rather be a plumber than a prince. This is a man who doesn’t know who he is, hence his notorious, and pitiful, grandeur. His favourite book is The Talented Mr Ripley, a novel about impostor syndrome.

That is the wreckage, now comes the fun: ours, because it is easy to laugh at them. The Yorks have a role, and the king knows, and – I think – uses it: to make the rest of the family look better, because they are not them. Channel 4’s satirical sitcom The Windsors was accurate in its depiction of Andrew as a used car salesman, and of Sarah as an insatiable freeloader. If they are broken, they are also absurd. Andrew loves teddy bears and beauty queens, a contradiction that can never be resolved. Sarah wanted helicopter motifs sewn into her wedding dress, presumably as a tribute to him. During It’s a Royal Knockout, she urged Meat Loaf, a potential beau, to steal Andrew’s panda mascot and stuff it down his trousers. She thought she, and later her daughter Beatrice, was the reincarnation of Queen Victoria; she consulted clairvoyants the way the rest of us consult GPs. Her waxwork at the Friargate museum in York was remade as Nell Gwyn, which must hurt a woman; she almost appeared in Baywatch. Sarah once, Lownie claims, asked a suicidal friend to question the spirit of JFK Jr about his love life, should the friend make it to the isle of the dead; she temporarily “adopted” a sherpa, whom she called Yeltsin. Her self-pity, which she tends through a series of memoirs, equals her ex-husband’s. I suppose there have been madder royals. Vlad the Impaler comes to mind.

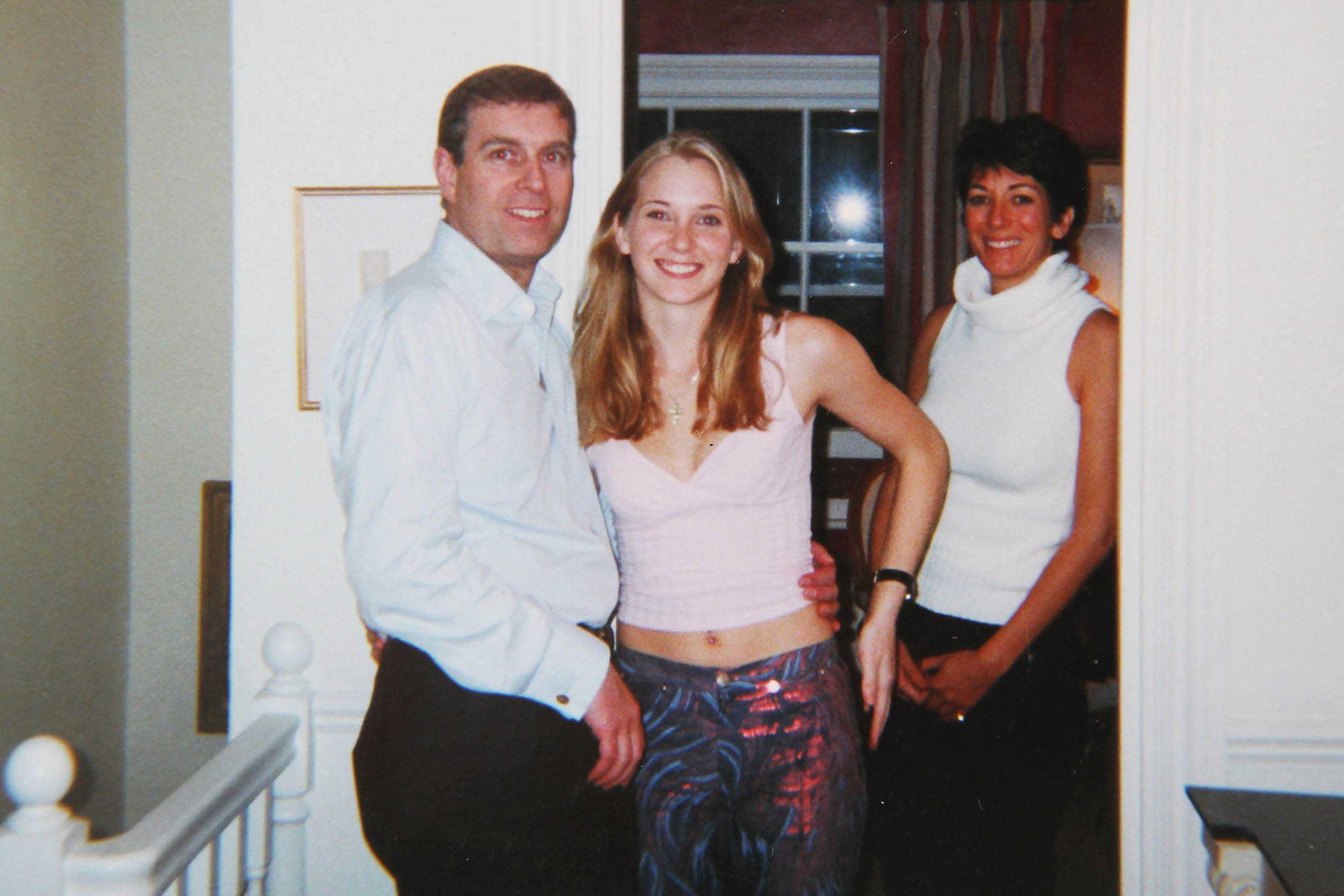

‘There is nothing a bad man loves more than a worse one’: Andrew with Jeffrey Epstein in New York, 2011.

Contrary to their self-image, which is all victimhood, the Yorks are studies in corruption. He is Tony Soprano in a coronet, weeping; she tried to sell access to him to the News of the World for £500,000 (“I’m a complete aristocrat,” she told the journalist. “Love that, don’t you?”). Her nadir was lecturing working-class people on how to eat healthily in the documentary The Duchess in Hull (“I won’t have to eat what they eat, will I?” she asked). His was an affection for Jeffrey Epstein, who he entertained at Balmoral, Windsor Castle and Sandringham. His need for Epstein is easily explained: there is nothing a bad man loves more than a worse one, and “Lolita Island”, Epstein’s retreat in the Virgin Islands, was much closer to the absolute monarchy Andrew craves than Buckingham Palace and its receding moat of liberal democracy. “We are very similar,” Epstein once said of Andrew, “We are both serial sex addicts.” Of his compulsive travel – both Yorks do it, they flee from themselves, and they always fail – I thought: does he miss the navy and his helicopters? Is that where he felt safest: in wartime?

But there is no inner life in this book, just a list of accusations and defences, appetites and sorrows. Divorced, the Yorks live together at Royal Lodge in Windsor, a house that sounds like merchandise. The king, who is Solomon compared to his younger brother, supposedly wants them out, and it is briefed that Prince William calls Andrew “a tosser”. The Yorks exist chiefly as an argument against – and demonstration of – the hereditary principle as it truly is. Still, they remain valuable as a caution against hubris, a tableau of unresolved childhood trauma, and as a metaphor. Lownie says they were given a dustbin decorated with their faces as a wedding gift, and nothing in this agonising drama is more apt.

Entitled: The Rise and Fall of the House of York by Andrew Lownie is published by William Collins (£22). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £19.80. Delivery charges may apply

Photography by Samir Hussein, WireImage; Jae Donnelly

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy