When Lara Feigel lost a legal battle with her ex-husband over custody of their son, what shocked her more than the verdict were the arguments used against her in court, which seemed to belong to a different era. An article she wrote on Donald Winnicott and maternal ambivalence was read aloud. She was, she says, “criticised for being too wilful, for writing books, for owning property” and told she was not “emotional or repentant enough” to be the kind of mother who puts her children first.

As a distraction, Feigel – a writer and professor of modern literature and culture at King’s College London – began reading compulsively about other custody cases. Her new book traces the evolution of custody laws through the stories of the women forced to challenge them, beginning with Caroline Norton in the 1830s, and ending with Britney Spears – two women who became “test cases for generations of mothers who used their stories to probe their own notions of how much freedom a mother should be allowed”. She sees custody as the “knot where motherhood, ideology and power get tied together”. The children tend to be the biggest losers in these legal fights with no real winners, but it is the mothers who find themselves subject to public scrutiny and vilification when they fail to live up to the ideal of the dutiful wife and selfless mother.

As well as writing nonfiction, Feigel is a novelist, and her historical portraits are immersive and compellingly written, displaying a keen eye for the poignant, often heart-rending, detail. Caroline Norton was, like many women in this book, a brilliant writer and a political reformist who had the misfortune of marrying a reactionary man, one not only considerably less brilliant than her but also small-minded, insecure and resentful of his wife’s abilities, her vivaciousness and hunger for freedom. When Norton befriended many influential cultural and political men and became close to the Whig prime minister Lord Melbourne, her husband, George, felt humiliated and became increasingly violent. Eventually George took her three children and sued her for “criminal conversation”, as adultery was then known, with Melbourne. The 1836 trial, in which Norton had to be represented by Melbourne because women had no legal standing, was a media sensation: Charles Dickens reported on it for the Morning Chronicle. Although Melbourne won the adultery case, George kept the children. At the time, children were considered the legal property of their father. George left his children dangerously unsupervised, and the youngest died in a riding accident.

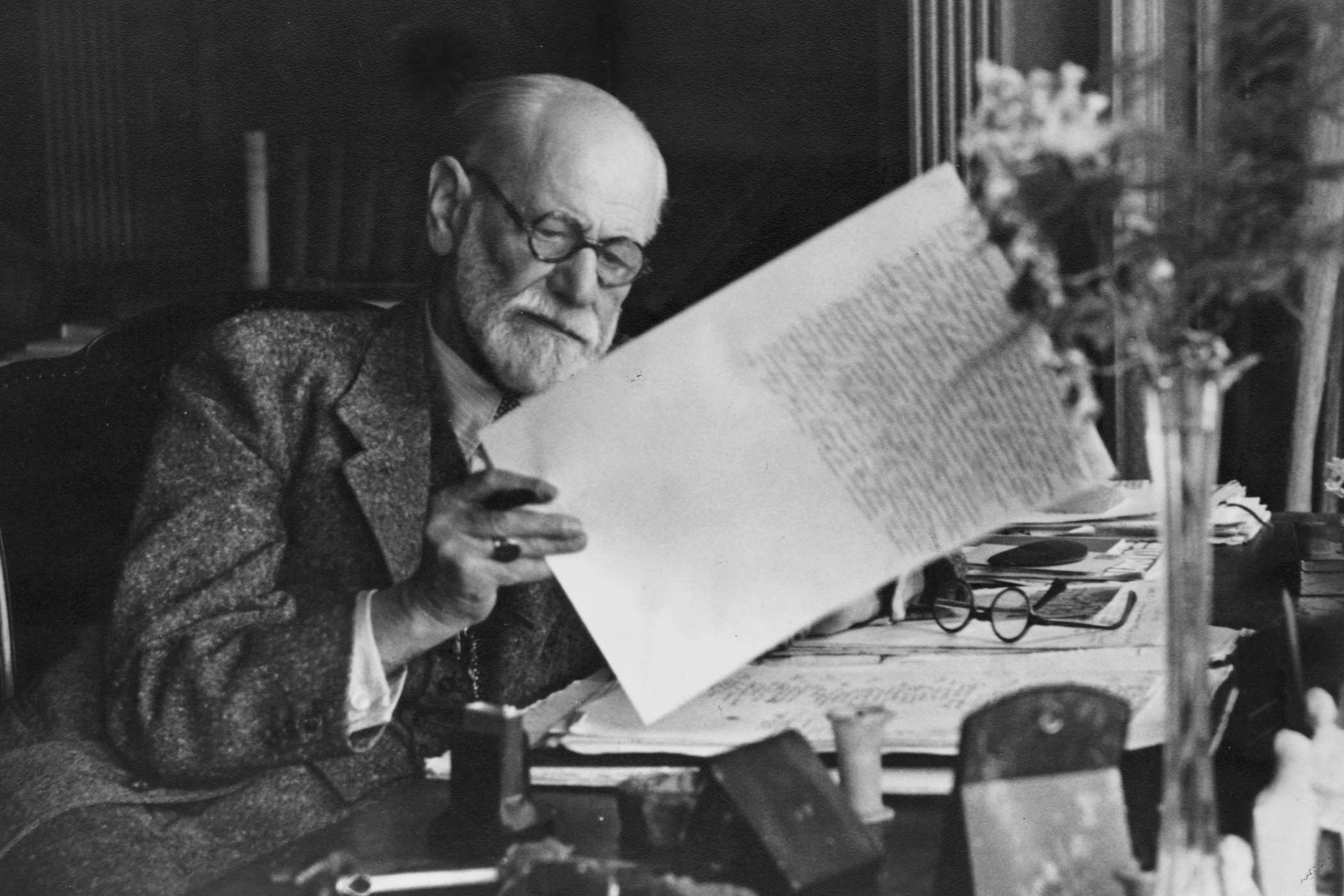

Caroline Norton (pictured) was, like many women in this book, a brilliant writer and a political reformist who had the misfortune of marrying a reactionary man

Caroline Norton (pictured) was, like many women in this book, a brilliant writer and a political reformist who had the misfortune of marrying a reactionary man

Norton became a campaigner, fighting for married women’s right to seek custody of their children. Her arguments emphasised the natural bond between a mother and her children. Surely, she argued in her pamphlets, a woman who has endured the “tedious suffering” of pregnancy and has “from her own bosom” nourished her child has some claim to care for them? Even then, many feminists wanted to avoid making such appeals and, as Feigel observes, motherhood remains a challenge for much feminist thinking: how should you reconcile the competing demands of emancipation and care? Greater recognition of the importance of motherhood paved the way for mothers to retain custody of their children after divorce, but it also created new reasons to remove children from mothers who were deemed to have fallen short of maternal ideals. The women Feigel profiles – George Sand, Frieda Lawrence (wife of D H Lawrence), Elizabeth Packer and Edna O’Brien – fought painful custody battles in which they were attacked for being unfaithful or holding radical views, writing provocative books or pursuing an independent career.

The epilogue, which provides a whistle-stop tour of modern-day custody cases, feels like the most urgent and important part of the book, and it is a shame this chapter seems something of a rushed addendum, because here we see how historic injustices persist. Feigel visits family courts across the country and learns how often lawyers rely on the scientifically debunked concept of “parental alienation”, the idea that a wounded and vengeful parent will, sometimes subconsciously, indoctrinate children against the other parent. Parental alienation is frequently cited as a reason to remove a child from their favoured parent, usually the mother.

At best, a claim of parental alienation means that children’s expressed desires are not considered or trusted; at worst, it means that children are returned to abusive fathers and a mother’s attempts to protect her children, are treated as evidence of said “indoctrination”. A 2019 study of 15,000 court cases analysed by the American legal academic Joan Meier found that mothers alleging sexual or physical abuse of a child lost custody half the time. Inside courtrooms, women are required to be perfect, Feigel notes, not only in their mothering but in their lack of hostility towards the father. Men are not held to such high standards.

She briefly mentions a few recent positive developments. The UK domestic abuse commissioner has recommended that parental alienation become ineligible in cases where domestic abuse is alleged, although it is unclear from the book if this has changed anything. New Pathfinder courts, piloted in Dorset and North Wales in 2022, interview children much earlier in the process and aim to encourage more out-of-court resolution, but it is too early to assess their true impact. Feigel argues, very sensibly, that trying to keep custody disputes out of the courts, where tensions are exacerbated, is key. She hopes one day mothers will no longer be held to impossible standards, and men will not find themselves trapped in forms of manliness that entail cruelty and bullying.

In Feigel’s view, one of the central dilemmas is the struggle to find ways that care and emancipation can coexist. And yet I’m not convinced it’s a problem to solve so much as a tension we build our lives around. As mothers – as people – we’re pulled in different directions, sometimes more or less insistently, between the care we owe to those we love and our desire for independence and self-fulfilment. We hope to live in a society that enables us to strike a balance that feels right, that minimises the number of difficult choices a person must make, and on this front most women in Britain today are not forced into the impossible positions that many of the women Feigel writes about were.

One might imagine that the author would come out in favour of shared custody arrangements. After all, one could insist that this question of care and emancipation is not a problem for women to resolve alone; men must take on care responsibilities too. But in a chapter on the American novelist and social activist Alice Walker, Feigel emphasises the perils of requiring children to shuttle between two different homes. After Walker separated from her husband, the Jewish civil rights lawyer Mel Leventhal, they split custody of their daughter, who moved between her mother and her father’s home every two years. Rebecca would later write about the difficulty of being continually uprooted and forced to move between two different worlds, the affluent all-white suburb where her father resettled, and the bohemian enclaves in Brooklyn and San Francisco where Walker lived and wrote. Rebecca’s is an extreme example, but Feigel believes that joint custody arrangements often split a child’s life between two parties in ways that don’t serve the child’s needs, particularly if the parents’ relationship remains acrimonious. In the early years after Feigel’s divorce, her son moved between her and his father every few days, but this proved too disruptive. It was “a brutal attempt to give him two homes that was in danger of leaving him unhomed” .

Her legal battle with her ex-husband began during the pandemic when she moved to the countryside and brought her son with her. It is unclear if the father was subsequently awarded full custody or a new joint arrangement.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

If joint custody is often not the answer, what is? Feigel believes courts need to place greater weight on children’s wishes, but in many cases it will place a huge burden on children to be asked to choose between parents. Perhaps the truly unfixable problem, and the reason custody cases are so often tragedies, is that most children would wish to be raised by two blissfully married, happy parents, but life can’t always give them that.

Order a copy from of Custody: The Secret History of Mothers fromobservershop.co.uk for £22.50.

Photograph by Corbis/Getty Images