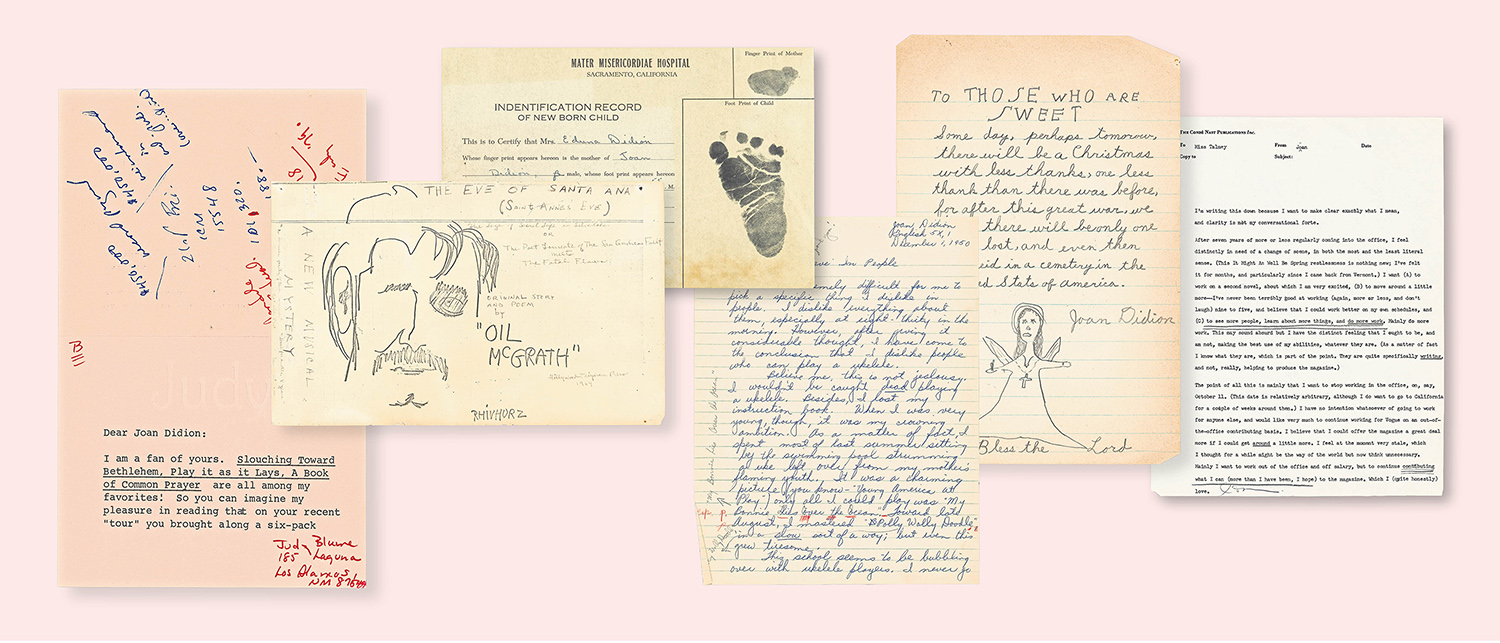

“Why did I write it down?” Joan Didion asked herself in 1966, looking back at an old notebook. “In order to remember of course, but exactly what was it I wanted to remember? How much of it actually happened? ... Why do I keep a notebook at all? It is easy to delude oneself on all of those scores.”

In recent weeks, Didion’s notes have become news, with the publication in book form of the most intimate imaginable record: private accounts of sessions she had with a psychiatrist at the age of 65, when she was undergoing, in her own words, “what probably amounted to a late-life crisis”. The notes read like a cross between a diary and a letter. The psychiatrist, Roger MacKinnon, is quoted at length, though the dialogue is of course only what Didion chose to remember (“it is easy to delude oneself”). The notes offer plenty of insight into who she was as a child and as a writer, wife and mother. But are they any of our business? Should they have been published at all? The book has prompted as much outrage as intrigue.

When Didion died at the age of 87 in December 2021, having outlived her husband by 18 years and their daughter by 16, her heirs made two important decisions about her effects. First, they offered up for sale via a modest auctioneer in upstate New York more than 200 lots of Didion’s art, books, furniture and ephemera, most of which sold for several thousand per cent more than their estimates. Eighteen volumes of the US army publication Vietnam Studies, valued at $200-$400, went for $2,700; three pairs of silver candlesticks, priced at $100-$200, sold for $8,000; a 1977 oil portrait of Didion, estimated at between $3,000 and $5,000, reached a hammer price of $110,000.

Much of the value of these objects derived from their association with Didion herself, a brilliant and by then much-imitated author who set a unique precedent for creative nonfiction writing and around whom a global fanbase had arisen.

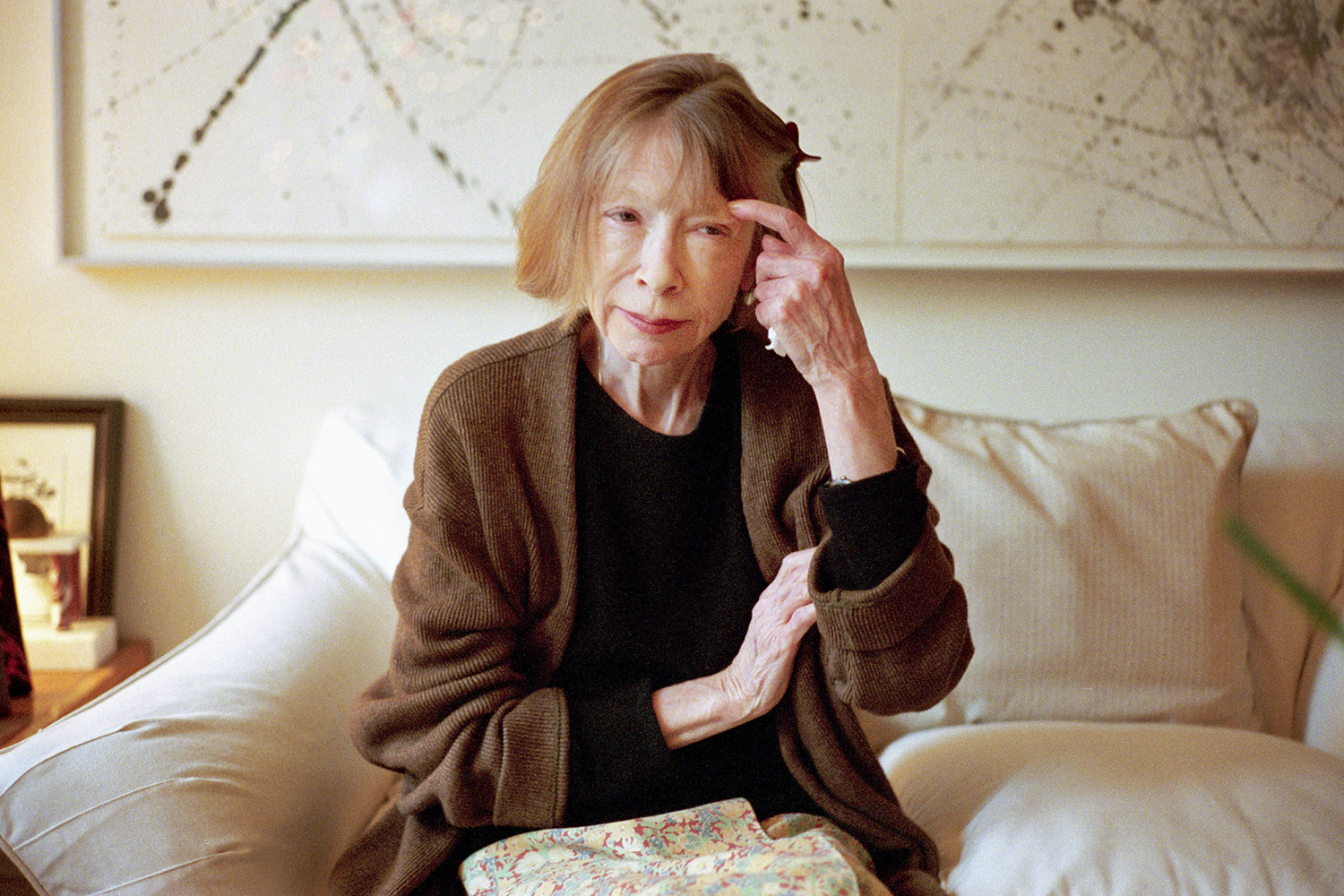

To call it a cult would be to diminish its scope and her talent. She was, however, much photographed; in her later years, she modelled sunglasses for the luxury fashion brand Céline and featured on tote bags produced by a literary magazine – which goes some way towards describing the niche she occupied: both “in” and omnipresent.

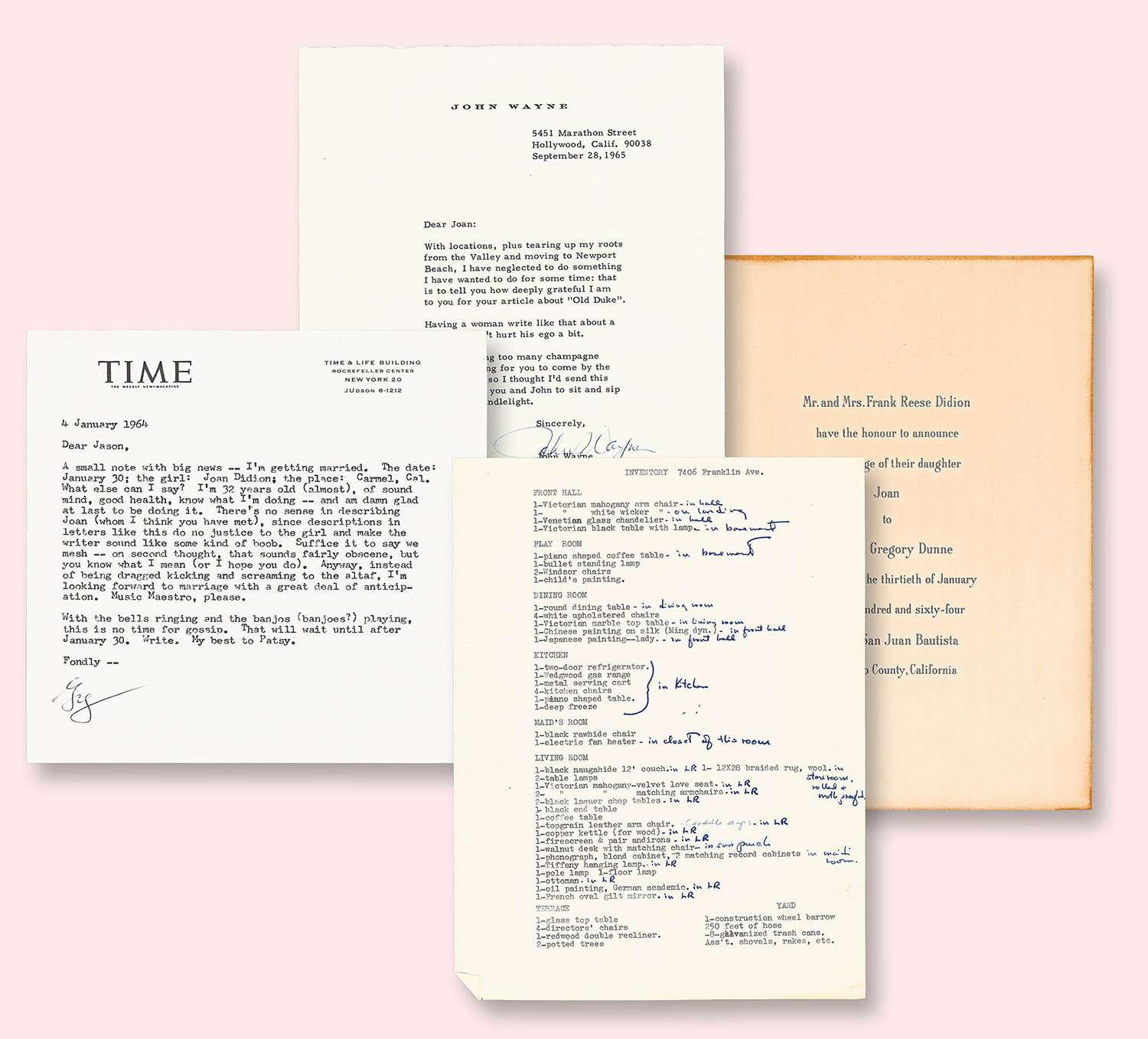

The second decision made about Didion’s possessions was to sell her papers, inseparable from those of her husband and frequent collaborator John Gregory Dunne, to the New York public library.

The couple’s joint archive included extensive correspondence spanning six decades, with family members, fellow writers and public figures; several hundred photographs; books, annotated and inscribed; typescripts, diaries and drafts. Once catalogued, they amounted to 336 boxes.

In the midst of this personal material were 150 pages of typed notes, unnumbered but printed out and neatly arranged in chronological order, in which Didion reported on sessions she had with MacKinnon between December 1999 and January 2002. (She went on to see him for a further decade, but the detailed notes end there. MacKinnon died in 2017.)

The notes also suggest that my intuition about their exclusion of Quintana wasn’t wrong

The notes also suggest that my intuition about their exclusion of Quintana wasn’t wrong

The sessions had begun at the behest of Didion and Dunne’s daughter, Quintana, who had told her own psychiatrist that her mother was depressed. The relationship between mother and daughter was thought by Quintana’s doctor to be at the core of Quintana’s difficulties – acute at the time – and the two psychiatrists conferred.

Didion’s notes are written in the second person; the “you” in them is her husband, John. Were they really meant for him? Did he see them? Impossible now to know. Didion was, in a sense, minuting the meetings: Quintana’s welfare – the core subject of these sessions – was their joint concern.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Two years after this record ended, Quintana would be dead at the age of 39 after a series of severe illnesses that might have been caused by her alcoholism and that coincided with the sudden death of her father, who suffered a heart attack on his return from visiting her in intensive care.

The heirs to this written material – the relatives who, judging by the auction in upstate New York, had vastly underestimated Didion’s value at the time of her death – are the children of her late brother, Jim. In the 150 unnumbered pages Didion describes to her psychiatrist a “great unspoken conflict” she and Jim had for some time over their parents’ wills. Jim’s children feature in these psychiatric notes too: they make a cameo appearance as the cousins to whom Quintana was least close.

It’s common for the archives of individuals to be sealed, at least in part, for some time, but when Didion’s papers were acquired by the New York public library no restrictions were placed on access. What to do, then, with these exceedingly private pages of notes about Didion’s – and by extension Quintana’s – therapy?

That decision was left to Didion’s literary executors – her agent, Lynn Nesbit, and two of her longstanding editors – who had discovered them in a filing cabinet in the first place. Reading between the lines of the eventual (unsigned) preface to the recently published book, Notes to John, one wonders whether they all felt unequivocally that the pages should be published, or whether their hand was forced by the terms of the library’s acquisition. Speaking to the New York Times, Nesbit conceded that the cache of notes “wasn’t written to be published”. So why publish them?

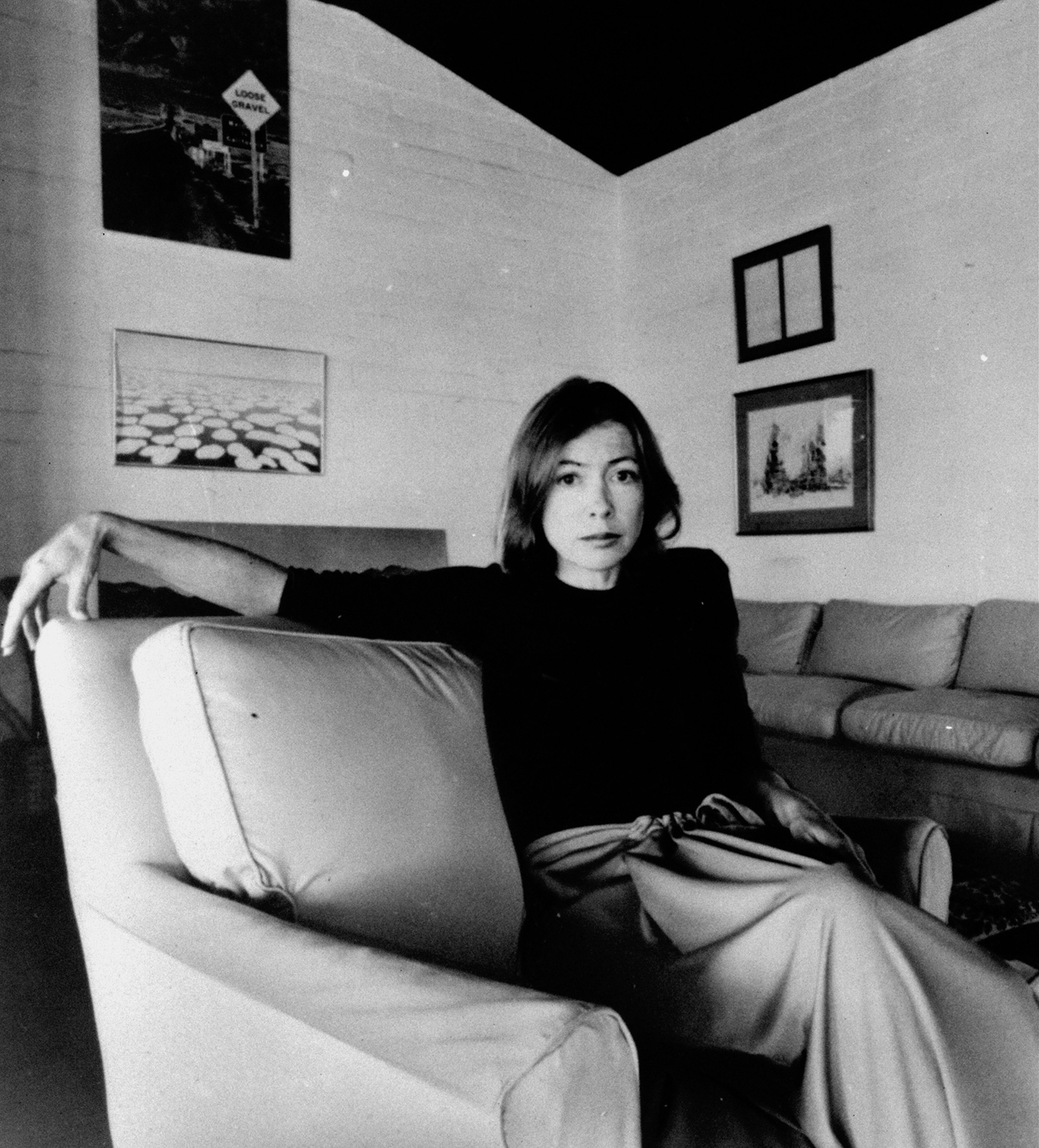

Didion was always inclined to talk to you in her writing, and to talk to herself, to puzzle things out. She was plain-spoken as a matter of principle, but the shape of her sentences, with their cascading clauses, showed you how carefully she crafted her thoughts. At the age of 15 she had typed out Ernest Hemingway’s short stories, enamoured of his “liturgical cadences”. By the time she was in her 20s, she had come up with her own astute and languid style. She wrote pieces that foregrounded the first-person pronoun and essays in which her all-seeing eye absorbed the layers of connivance and corruption in the politics of the time: “a way of looking but not joining”, as she put it. There she was on the periphery, and if you read her, you would follow her anywhere.

Over the first few decades of her career, Didion alternated essays with novels, but then in 2003 she published Where I Was From, a memoir she’d started to write 20 years earlier and only brought herself to finish after the death of her parents. When, in the final days of that year, Dunne died at the dinner table, Didion had been writing notes towards a novel. She never reread them, and never wrote a novel again.

From that point on, she became a memoirist. With The Year of Magical Thinking, a book about her grief over Dunne, Didion’s selectively personal style evolved into one that was more visibly raw. The book was a bestseller. Overnight, Didion gained a much broader readership in an era when the personal had ceased to be political and the confessional was everywhere.

A confession of my own: I had admired Didion with ardour for decades when The Year of Magical Thinking was published in 2005. I was struck by the beauty in its self-examination, yet while others waxed lyrical about its contents, I became more and more disconcerted by the story that seemed to be missing from it. Didion, who had spent her career exploring the underside of things, had, in giving an account of her own life, left a palpable hole where her child should be. In the book’s opening section, Quintana is hospitalised and unconscious; in the ensuing pages, she appears to be a mere bystander to the romance between her parents, excluded from the main event.

Here was grief as a form of narcissism, and the way the world lapped it up made me anxious. Still, when I learned that Quintana had died after the book was written – and just two months before publication – I felt guilty for having thought ill of Didion’s parenting at all. Seven years later, she published Blue Nights, a book in memory of Quintana.

Notes to John sheds intriguing light on the question of Quintana’s part in the family dynamic – and helps to answer some of the complicated emotions raised by the earlier books (in itself perhaps one argument for its publication). What I had at first interpreted as maternal neglect might well have been discretion. In The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, Didion evidently constructed a personal story from what remained once she had omitted the private one. In the gaps of her written account there was this: the rehab centres, the late-night phone calls, the difficulty of saving Quintana from herself.

The notes also suggest, however, that my intuition about Quintana’s exclusion wasn’t wrong.

“Quintana has the strong sense,” MacKinnon tells Didion early on, “that when she deals with you and your husband she is dealing with a single person. He suggests she sometimes feels herself to be “an outsider in a family of two”. Her mother’s favourite expressions, Quintana says, were: “Brush your teeth, brush your hair, shush I’m working…”

“Maybe you dealt with her at a distance,” MacKinnon suggests.

“I dealt with everybody at a distance,” Didion says.

However enlightening a view this new book offers of Didion, as a writer and as a mother – what readers might prize as Didion’s cool ironies, Quintana seems to have felt sometimes only as coldness; do we have the right to read it? Is everything that a writer commits to paper part of her life’s work? If you look hard, you realise Didion herself had explored those questions several times.

At a dinner party she once attended in California, an English professor attempted to argue that F Scott Fitzgerald’s unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon, was proof that he was a bad writer. When Didion protested that a writer could not be judged on the basis of unfinished work, the other dinner guests countered that because Fitzgerald’s notes and outline for the book existed along with the written portion, readers knew perfectly well what the novelist had intended. Didion later recalled the episode with a powerless kind of shock. “Only one of us at the table that evening,” she wrote, “saw a substantive difference between writing a book and making notes for it.”

Some years later, an unfinished novel by Didion’s idol Hemingway was dug out by his fourth wife and “condensed” for publication by his son. Hemingway had struggled with this book for some time and, prior to brain-charring bouts of electroconvulsive therapy, had been categorical about material he did not want published after his death. His widow had gone on to publish all of it regardless. In reporting on this in 1998, Didion was scathing. She described passages of the unfinished Hemingway book as “something not yet made, notes, […] words set down but not yet written”. It’s a beautifully precise description that might guide us in our reading of Didion’s own posthumously published work.

In a 2006 interview with Hilton Als, published in the Paris Review, Didion made clear how much rewriting she did when working on a book. “I constantly retype my own sentences,” she said. “Every day I go back to page one and just retype what I have. It gets me into a rhythm. […] At the end of the day, I mark up the pages I’ve done […] so that I can retype them in the morning.”

Als asked whether she did that with The Year of Magical Thinking, a book that seemed to have more immediacy. “I did,” she replied. “It was especially important with this book because so much of it depended on echo.” She was, in other words, a compulsive redrafter. Whatever else her notes are, they are not what she would have called a book.

So how might her executors justify the publication of Notes to John? They might argue that, unlike Hemingway, Didion had not, to anyone’s knowledge, expressed a wish about the material she left behind. There was, too, a precedent in her lifetime for the publication of her notebooks. South and West: From a Notebook, a slight volume made up of two sets of jotted reflections, was published in 2017.

And anyone who remembers the convoluted emotional blackmail in The Aspern Papers, Henry James’s story about a scholar in search of a dead poet’s letters, might have some sympathy for Didion’s executors’ dilemma. They were aware that with the publication last year of Lili Anolik’s intensely subjective Didion and Babitz, Didion-bashing was already under way. A few recent biographies have begun as authorised lives and wound up breaking with their subject’s estate during the writing process (Jonathan Bate on Ted Hughes and Benjamin Moser on Susan Sontag come to mind). In this context – and given the public accessibility of the material – they might have concluded that immediate presentation, with minimal framing, of her notes was preferable to a later “discovery” by a potentially irresponsible biographer.

Didion’s great fellow reporter Janet Malcolm once wrote, in her book about Sylvia Plath, about the notion of the unsent letter. What interested Malcolm was not the non-sending but the retention of the letter by its author. “By saving the letter ... we are, in effect, saying that our idea is too precious to be entrusted to the gaze of the actual addressee, who may not grasp its worth, so we ‘send’ it to his equivalent in fantasy, on whom we can count for an understanding and appreciative reading.”

If the notebooks that have become Notes to John were to be interpreted this way, the fantasy addressee would most likely have been Didion’s own future self. All of her life she observed and processed things by setting them down on paper, and it’s perhaps a mark of her evolving indissolubility from Dunne that these notes to self were addressed to him. One of the most touching elements of Notes to John is that in the course of it, Didion presents to MacKinnon other notes she made in 1955, when she saw a psychologist at university. She had kept these jottings for 45 years, and they seemed to be intended for just that moment, when they would be resurrected for comparison.

But given the fact that this document has been made available to us, what are our responsibilities as readers? What do we owe its author? A breach of privacy doesn’t have to be an invasion of it. We could, instead, choose to adopt the position of Malcolm’s “understanding and appreciative” recipient.

“See enough and write it down,” Didion told herself, “and then some morning when the world seems drained of wonder, some day when I am only going through the motions of doing what I am supposed to do, which is write – on that bankrupt morning I will simply open my notebook and there it will all be, a forgotten account with accumulated interest, paid passage back to the world out there.”

Those words seem tilted now into a new light. To which world did Didion fantasise that she would earn a return? To this one, perhaps: the one in which we are reading what survives of her as generously as possible and treating it with the same wonder she hoped to discover.

Order Notes to John at observershop.co.uk to receive a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

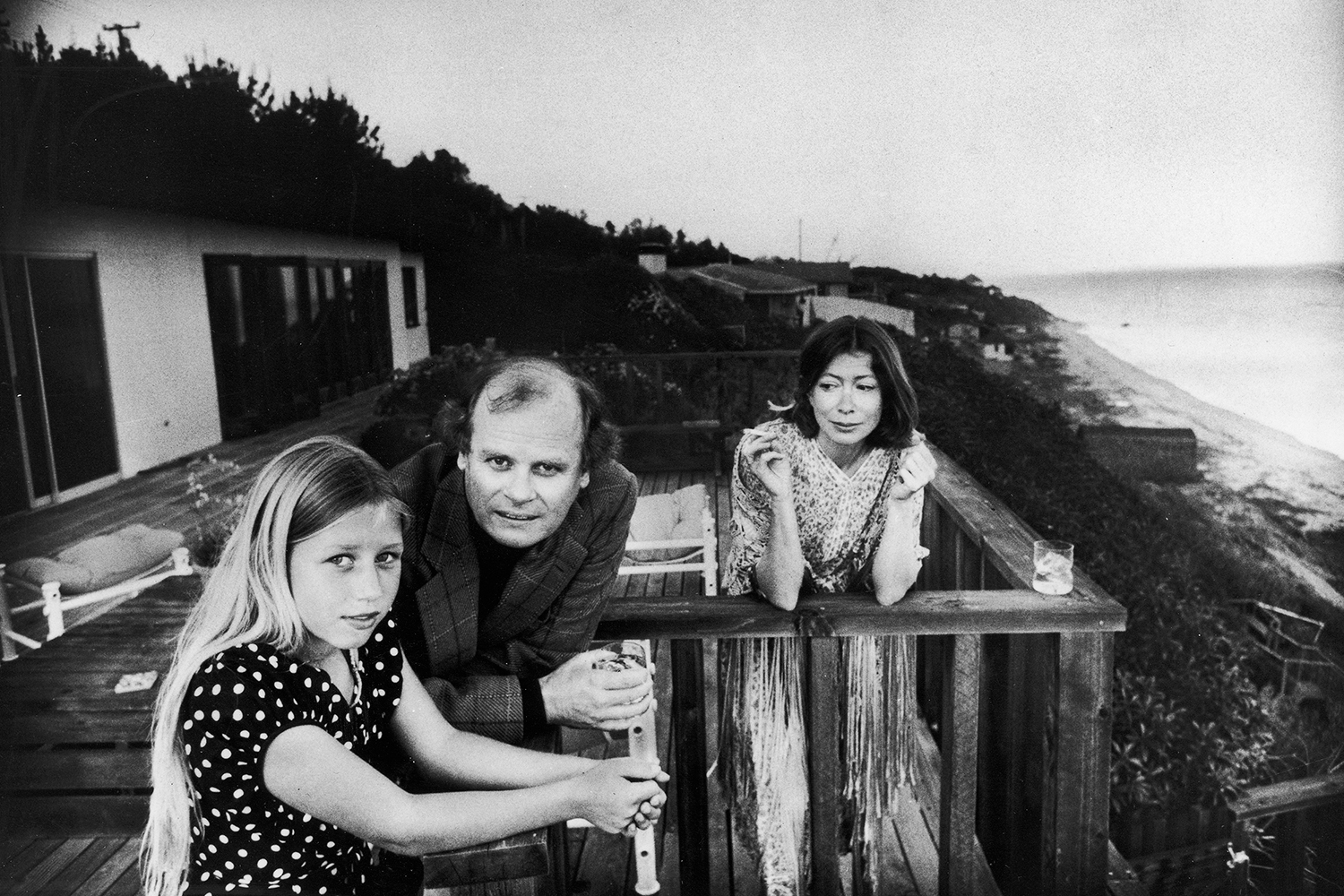

Photographs: Neville Elder/Corbis/Getty Images