The late Christopher Hitchens put me on to the word. Years ago, while pontificating about al-Qaida on TV, he insisted that most Muslim fundamentalist groups weren’t just fighting the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq by the US and its allies: “They are fighting for the restoration of the lost caliphate.” Caliphate. I remember wondering what it meant. Later, when those gruesome hostage videos of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (Isis) appeared online, I heard the word again. By then I knew that it referred to a form of Islamic leadership that had ended after the fall of the Ottoman empire. And yet I couldn’t help associating it with those scenes of barbaric violence.

Back in 2014, when Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, then the leader of Isis, declared that the terror group had established a caliphate in the territory under its control, the majority of Muslims all over the world didn’t perceive their claim as legitimate. Indeed, as the journalist Imran Mulla points out in his first book, The Indian Caliphate, the Ottoman caliphs themselves “would all have been outrageous heretics in the eyes of Isis militants, and certainly don’t fit the stereotype drawn up by hawkish western governments and commentators”.

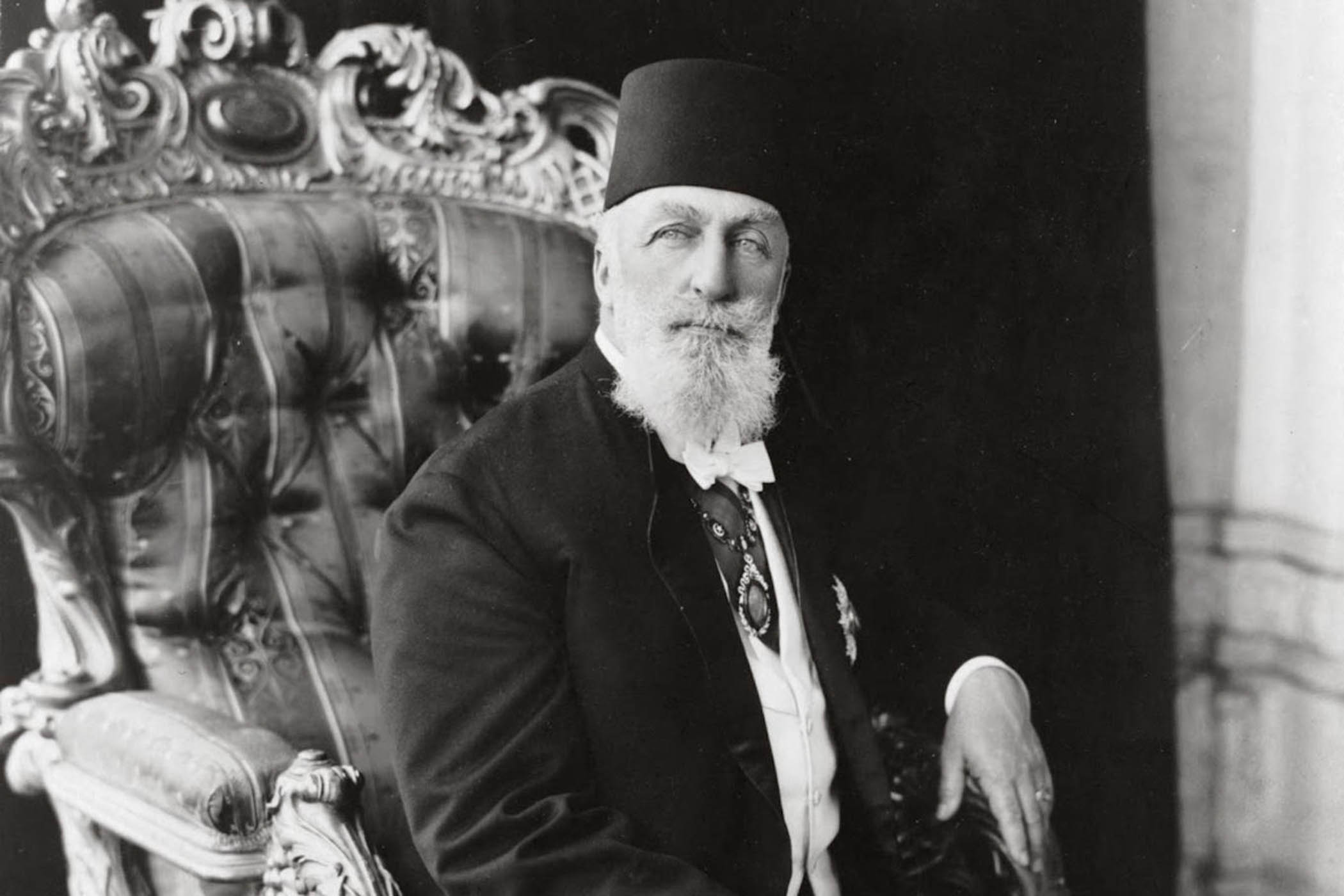

Abdulmejid II, the central protagonist of Mulla’s book, was the last prince from the Ottoman dynasty to be appointed caliph, for about 15 months, between 1922 and 1924. He adored all things French and liked to spend his days painting nudes, hanging out with Turkish poets, and playing the piano and the cello. He spent almost three decades of his early life under house arrest in Istanbul, because the sultan, his cousin, was afraid of any potential claims to the throne from his family members.

After Abdulmejid was deposed as a caliph by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s secular government and bundled into the Orient Express overnight with his wives and children, he lived out the final two decades of his life in exile, first in Switzerland, then in France. Mulla writes that despite being “necessarily reclusive, he was nonetheless cosmopolitan in outlook; enamoured by Europe yet devoted to Islam”. Hitchens would probably have been baffled by this image of a cello-playing caliph.

Above: Abdulmejid on the day he was appointed caliph in 1922 and, main picture, photographed by Jean Pascal Sébah the following year.

The book begins with a detective story: why is there a tomb for Abdulmejid, built in the Ottoman style, in Khuldabad, a rural outpost in western India? And why wasn’t the last caliph buried there? The tomb was built in the 1940s by Osman Ali Khan, the seventh nizam (sovereign) of Hyderabad, among the wealthiest men alive at the time. With the fall of the Ottomans, the nizam, though under the protective umbrella of the Raj, presided over a princely state the size of Italy in the Indian subcontinent and became the world’s foremost Muslim ruler. The nizam paid Abdulmejid a pension, partly to save the exiled caliph and his family from destitution but also because he felt guilty for endorsing anti-Ottoman sentiments under British pressure during the first world war. This connection between the Ottoman exiles and a crazy rich Indian Muslim potentate grew into a full-fledged union in 1931, when the former caliph married off his only daughter, Princess Durrushehvar, to the nizam’s eldest son and heir, Azam Jah.

In 2023, Mulla chanced upon a legal deed, purportedly signed by the last caliph, transferring the title of the caliphate to the “firstborn son of this new kinship”. Experts subsequently suggested the document might be fake, but regardless of the provenance and authenticity of the deed, Mulla argues that it wouldn’t have seemed implausible to think of Hyderabad as a potential seat of the caliphate in the first half of the 20th century. Before the partition of 1947, the subcontinent had the world’s largest population of Muslims. Following the decline of the grandiloquent Mughals who ruled over much of present-day south Asia for more than two centuries, Ali Khan had successfully positioned himself as heir to India’s glorious Islamic past.

Multiple Raj officials cannily hyped up the British crown as a natural successor to the Ottomans and the world’s “greatest Mohammedan power”. The Muslim League in India launched a popular campaign to advocate for the Ottoman cause after the first world war. Mulla overstates things by calling the the Khilafat (meaning caliphate) movement the country’s “first ever mass protest”, but the cause did mobilise massive numbers of Hindus and Muslims together in a display of anti-colonial solidarity that significantly shaped British foreign policy in Turkey.

Silence over inconvenient instances of state-sponsored violence has long been a feature of the world’s largest democracy

Silence over inconvenient instances of state-sponsored violence has long been a feature of the world’s largest democracy

Mulla adroitly evokes the whims and regrets of the figures in this absorbing intercontinental account. Princess Durrushehvar, for instance, never forgave the Turkish nationalists for their unceremonious treatment of her family. In 1935, at a royal reception in London, the Turkish prime minister Ismet Pasha tried to greet her but she wouldn’t let him kiss her hand. Even though Ali Khan’s wealth and jewellery stash rivalled that of Henry Ford and Rockefeller, he still turned up everywhere in inexpensive clothes and frowned upon those who reached for second portions at dinners in his palace.

Then there are Shaukat and Mohamed Ali, Muslim brothers brought up by a single mother in northern India, who were radicalised by their English-style education in India and Britain, and became instrumental in starting the Khilafat movement. As a representative of the campaign, Mohamed even secured an audience with the pope in Rome and found the pontiff sympathetic to their twin causes of Gandhian civil disobedience against colonial rule and protecting the “integrity of Islam” through the caliphate.

Shaukat was the brains behind the strategic marriage alliance between Princess Durrushehvar and Azam Jah. A month after the wedding, in December 1931, he convened a global summit of Muslim leaders and intellectuals in Jerusalem in order to rally support for a possible revival of the caliphate. Turkish spies got wind of his plan and cautioned their British counterparts, who in turn forbade Abdulmejid from attending the conference. But representatives from more than 20 countries turned up and discussed everything from the Balfour declaration to Italian atrocities in Libya. The conference promoted the question of Palestine as a “global Islamic cause” for the first time – it was a unifying cause for Muslims just as the caliphate had been after the first world war.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Mulla dwells too long on his characters’ western credentials, perhaps out of an anxiety that they wouldn’t be otherwise deserving of empathy. The point about Abdulmejid dabbling in Orientalia in his paintings is well made, but do we really need to know that in due course “fantastical harem scenes gave way to authentic depictions of family life in the harem”? Mohamed Ali, of course, learnt to be more English than the English at university, but should the reader be apprised of his grooming habits at Oxford?

Osman Ali Khan, the seventh nizam of Hyderabad.

These are minor blemishes, however, in a book where the sense of impending tragedy is palpable on every page. Mulla’s account of Abdulmejid’s demise and the long search for a final resting place is poignant. The nizam did commission the construction of a mausoleum, but work stopped in September 1948 when Indian armed troops marched into Hyderabad with tanks to force the nizam – who had been encouraged by the founding father of Pakistan, Muhammed Ali Jinnah, to aim for independence for Hyderabad after partition – to throw in his lot with the Indian union.

The invasion was followed by one of the darkest chapters in Indian history, locally referred to in Hyderabad as “police action”. At least 27,000 people were killed in anti-Muslim massacres over the next two months, and many more were forced to move out of the state. Today, the Modi regime continues a policy of blatant Hindu supremacy and Islamophobia, but silence over inconvenient instances of state-sponsored violence has long been a feature of the world’s largest democracy. Decades after the killings, a visitor to Hyderabad will struggle to find any public memorial to the dead, or even an acknowledgment of the exodus. As Mulla writes, “Officially, this was an atrocity that never happened.”

The Indian Caliphate: Exiled Ottomans and the Billionaire Prince by Imran Mulla is published by Hurst (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Photography by Alamy