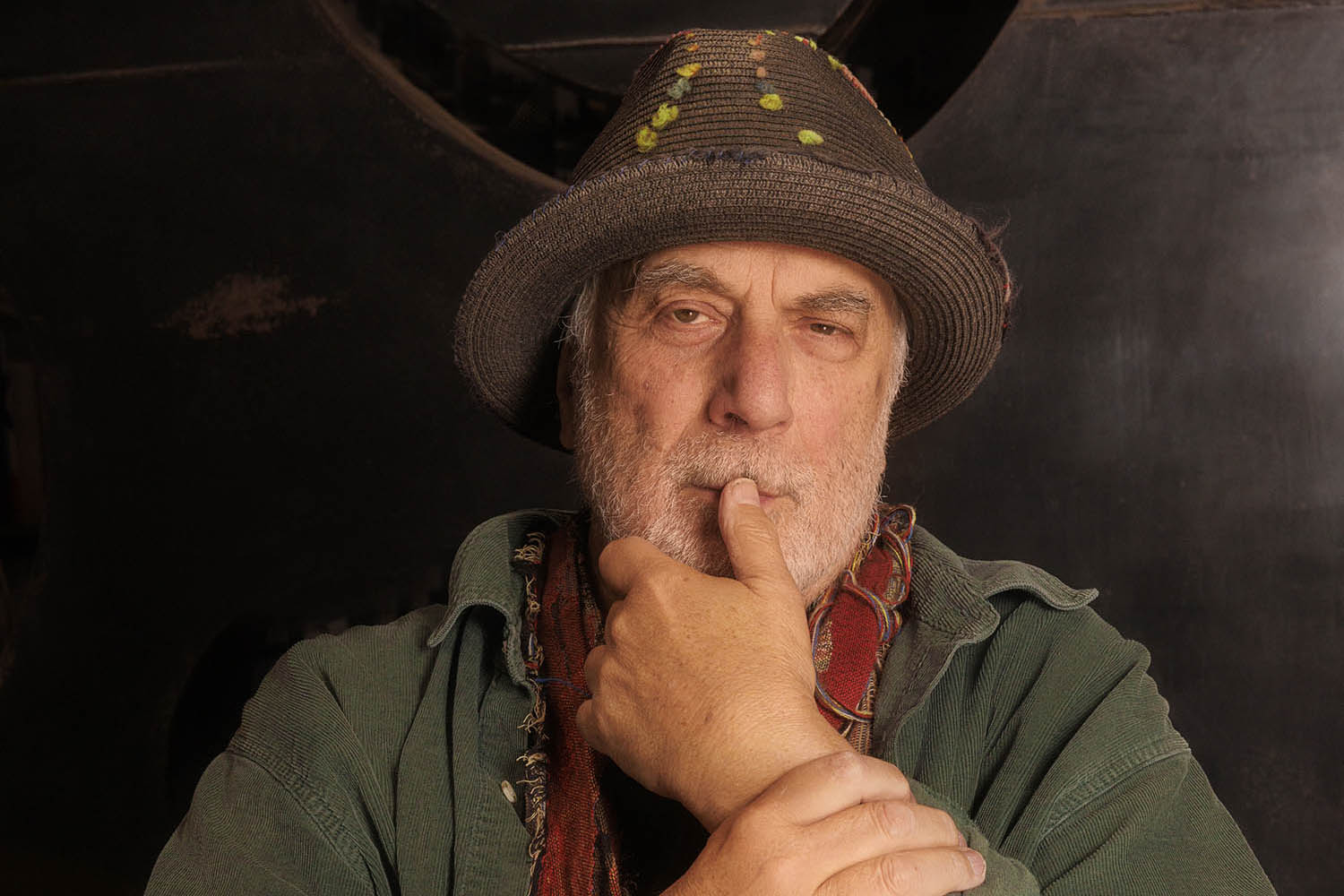

Photograph by Manuel Vazquez

When I arrive at Ron Arad’s studio, tucked behind a grisly road in Chalk Farm, north London, the 74-year-old artist and designer is finishing a Zoom call. He sits alone at a desk on a capacious mezzanine, the low hum of an office below. Arad closes the lid of his laptop and I lob him a gentle loosener: how’s he doing? “The good things are good,” he replies. “Lots of good things. And the bad things, including the world, are not.”

I ask him to expand. He sighs. “I don’t need to. You’re a journalist; you know.” I have a decent idea: Arad has lived in the UK for more than half a century, but was born in Israel, and is one of the country’s most celebrated exports. The conflict rages on. The day before, Benjamin Netanyahu met with Donald Trump, announcing he’d nominated the US President for the Nobel Peace Prize. “I think it has a big impact on everyone. Do I care? Yes, I do. Can I disconnect myself? No. Every direction you look, there are things you should be concerned about. And ‘concerned’ is a nice, easy word.”

It’s a heavy opening. Arad quickly retreats to more comfortable “good things” ground: an audio-visual run-through of his greatest design hits, sometimes using a projector screen and, on other occasions, nimbly jumping to his feet to show me one of the many prototypes dotted around the studio. It’s an eclectic space of metal and wood, once a piano factory and dilapidated fashion “sweatshop”, now effectively a gallery of his life and work.

Many of the classics are here: one highlight is an early version of the Rover Chair – a postmodern mash-up of a Rover P6 leather seat and structural metal tubing that launched his design career (he had worked as an architect prior). The chair became a sensation after Jean Paul Gaultier bought six, and then Vitra asked Arad to design for them. He is not especially precious about his work (his cats sleep on his Rover Chair at home in Belsize Park) even if some pieces – notably the D-Sofa, a curvaceous double-seater that Arad originally made from offcuts of steel lying around his studio – now sell for millions at auction. This popularity gives Arad quiet satisfaction: he’ll sometimes glance through a window and see his spiral Bookworm bookshelf, an icon of middle-class living. “The fact that I’m not the only one who likes it? It does give you joy.”

There are newer projects to discuss, too. Arad has a couple of pieces in the Royal Academy’s 2025 Summer Exhibition, including his playful riff on Rodin’s The Thinker called Dubito Ergo Cogito (“I doubt therefore I think”). The bronze sculpture invites visitors to perch on its plinth and contemplate the world – Arad shows me photos of Grayson Perry and Sir Paul Smith doing so. “At the Royal Academy people normally are not allowed to touch anything,” he says, pleased. “It’s out of character that people are encouraged to sit on a piece.”

Arad’s work, which spans art, design and architecture, shares qualities – humorous, provocative, even mischievous – with the man himself. He has been a larger-than-life force in the design world since the 1980s, one of few designers (along with, perhaps, Philippe Starck) to enter mainstream public consciousness, distinctive in part because of his signature black felt cloche hat. The “cappellone” (aka Hat 2000) was reproduced and sold as a limited edition by Alessi in 2000, the first time the Italian manufacturer had made a non-homeware product. He doesn’t wear it this afternoon, opting instead for a jaunty brown number with a bowler-hat brim purchased from a flea market and on to which he has sewn colourful dots of thread.

“Some people have good hair and some people have good hats,” he explains, lifting his to run a hand over the stubbly dome below. Then he grins, “I wish I belonged to the hair group.”

Arad is the perfect embodiment of his flamboyant work. He describes his early output as “irresponsible, juvenile, avant-garde” – he never imagined some would end up in shows at New York’s MoMA and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. He still has fun coming to work, overseeing a young team of 20 or so working on, say, a residential block in Tirana, Albania, or a public art project in the US. “I’m the oldest person in the studio, but I think I’m the most juvenile,” says Arad. “I’m surrounded by responsible adults; it is like a progressive kindergarten.”

I ask if he has considered retirement. His eyes dart to mine and he seems affronted, like I’m repeating a scurrilous rumour. “No, no!” he replies. “Because I have a lot to do. I haven’t finished!”

The slide presentation (which is what our interview is fast becoming) continues. Arad alights on one of his favourite pieces: Ping Pong, a concave table-tennis table made from steel and bronze. Arad has a reputation as a formidable, fearsome player, no doubt aided by the design of the table that curves upwards at both ends, slowing down the game and extending rallies. “I’m pretty good at table tennis on my tables,” he says. “I’m not very good at following conventions and rules, but I’m very good when I invent them.”

Ping Pong was first shown at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 2008. “Anthony Caro came and told me, ‘This is a wonderful sculpture,’” Arad recalls. “I said, ‘Thank you, Sir Anthony.’ And then he says, ‘You should try and play ping-pong on it.’” Arad guffaws at the notion that he wouldn’t have tested the table with a game. “It summed up the discussion between art and functional design: what is what? The national sculptor of the country saw my scuplture and thought it was his idea that you can play on it.”

Confusion over how to best describe what Arad does – is it art? Design? Something else? – has followed him his entire career. It reared up again in June 2021, when London auction house Phillips listed a 1993 handmade, patinated mild steel prototype of his D-Sofa with an estimate of £80,000 to £120,000. In fact, the piece ended up selling for more than £1.2m.

Arad was pleased; artists receive a percentage of their auction sales. But Phillips argued that the piece should be considered design, in which case Arad wouldn’t receive a penny. “The auctioneers refused to pay me the artist’s percentage because you can put your bum on it,” is how he sums it up.

The story is told as a comic one, though that might be because, with the help of DACS (the Design and Artists Copyright Society), Arad successfully contested the decision. But the debate, he thinks, misses the point. Arad often quotes Oscar Wilde: “It is absurd to divide people into good and bad. People are either charming or tedious.” It is the same, he argues, with his work. “Before I know if it’s art or design,” he asks, “is it exciting? Is it thrilling? Is it delightful, or is it not? Does the fact that you can sit on something make it less of an art piece? Sometimes it makes it more of an art piece. Hence the Rodin Thinker. If no one sits on it, it’s only half the piece.”

The desire to “thrill” has, consistently, been Arad’s preoccupation. His work rarely makes political points – though there are exceptions. In 2020, he produced a series of chairs called Don’t Fuck With the Mouse, a response to a request from Disney to celebrate Mickey Mouse’s 90th birthday, which riffed on Mickey’s distinctive profile. The project fell through, but for a special one-off, Arad embedded newspaper clippings from 31 January 2020, the day the UK left the European Union, into the chair’s clear polyester interior. Then he scrawled, in red paint, on the backrests: “What now?”

In the studio, Arad walks me round the finished version, informally known as the Brexit chair. He wafts his hand over the piece. “This I did purely selfishly. Maybe Nigel Farage will buy it and be very proud of it.” A pause, then a whisper: “I’m not going to let him have it.”

Our time almost up, Arad revisits that first tricky topic. He weighs up his words. “What’s happening is not acceptable, not tolerable, not justifiable or excusable, or whatever word you want to use.” He seems uncomfortable on this subject – concerned, maybe, that whatever he says could feel insubstantial or be misinterpreted. “For me, it’s not about taking sides. It’s about seeing what we can do to stop it.”

“I have my opinions,” Arad continues, with a weary headshake, “but I’m not an activist. Maybe I should be, but I’m not.”

For Arad, his work will always to some degree be escapist – and when “the bad things are bad” he returns to that. “Why do we live?” he asks. “We live for the joy of poetry, music, art, architecture… Although what we do [as artists and creators] is surplus to requirement, I want to believe it has a role. Sometimes it’s direct – art can be a flag or a poster – but it doesn’t have to be. Sometimes your work is drafted to a cause, sometimes it isn’t.”

As he shows me to the door, I ask, “So it’s enough if an object you create is just beautiful?” Arad looks aghast. “Don’t say ‘just beautiful!’” he fires back. “If something is beautiful, it’s not ‘just’.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy