Whenever I see a photograph of some young novelist grinning away beneath the headline “Film rights for Steve Author’s Up the Shitter optioned by Massive Package Films” and Steve Author is quoted as saying something like, “I’m really looking forward to seeing Up the Shitter on the big screen”, I think, “Ah, God love you and good luck to you, son.”

Gather round children while I tell ye a tale of woe and pain. A decades-long saga of suffering and endurance to rival The Odyssey itself. The story of how a novel tries to become a film. But first, the fun part…

Having the idea.

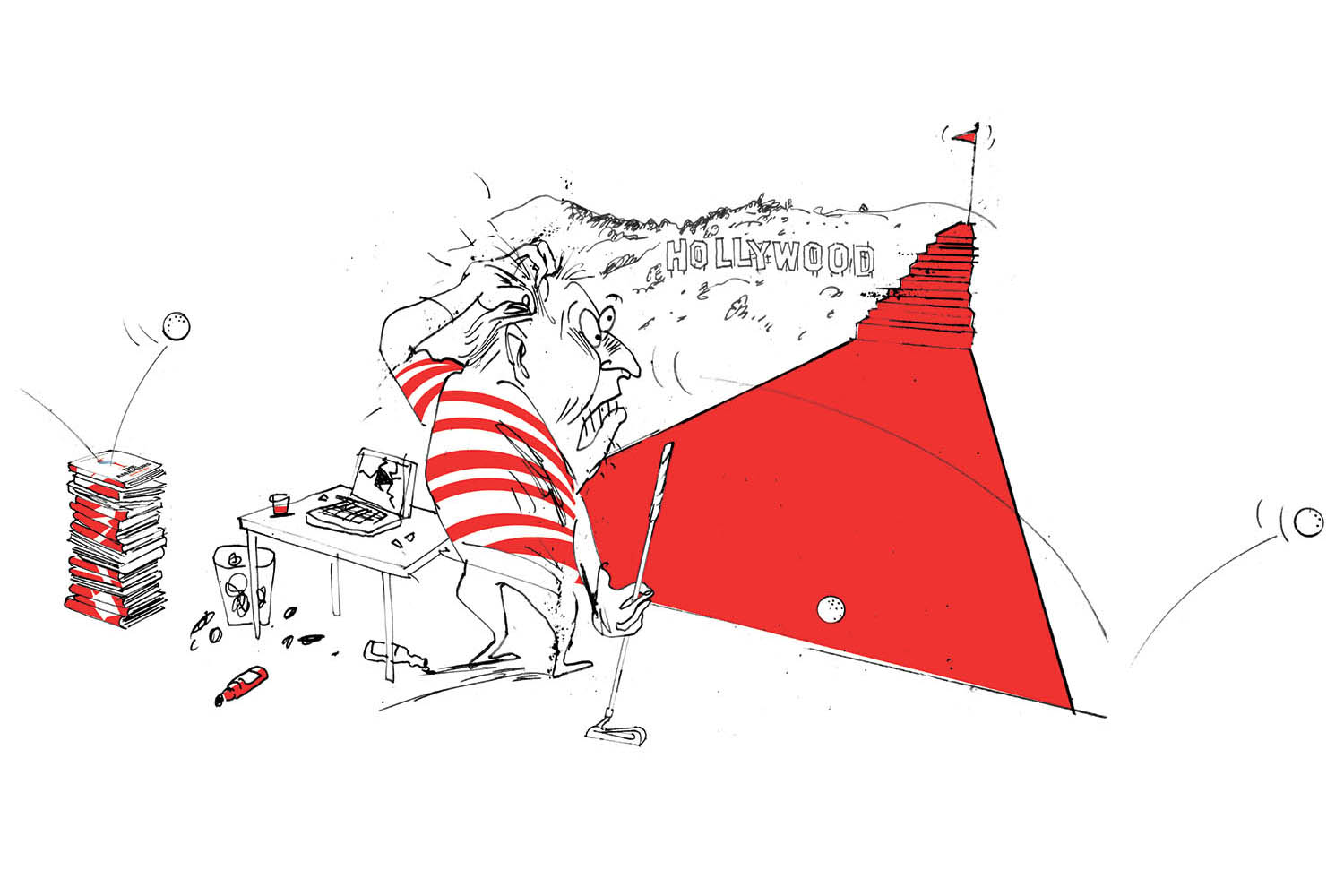

I first had the idea for The Amateurs on Kilkee golf course in County Clare, south-west Ireland in August 2005. Exactly (and chillingly) 20 years ago this month. Back in 2005, I was struggling with my game. I remember trudging after yet another bad shot and thinking something like “maybe if I smash myself in the head, I can reset my brain”. The elevator pitch came quickly. As Griffin Mill insisted in The Player, it was indeed 25 words or less.

World’s worst amateur golfer gets hit on the head by a stray ball and sent into a coma. He wakes up with the perfect swing.

This isn’t quite as crazy as it sounds. As I got into the research, I talked to a neurologist. There are many documented cases of people suffering severe head injuries and coming out of comas with skill sets – both physical and mental – they never had before. Complex mathematics. The ability to play piano.

But we needed to bake in some jeopardy, too. Some less desirable side effects. I found a candidate in the research: coma patients waking up and being perfectly normal apart from “extreme hyper-sexualisation”. (Readers of my novels can well imagine the record scratch and fast camera pan back as I read this line.) Some were driven to masturbate compulsively, frequently and even publicly. Well, we’ll have all that. I also wanted to give Gary (as I was calling my poor protagonist by this point) Tourette syndrome, but I feared this might be going too far. “When it comes to the brain,” the neurologist said, “we know so little. It’s almost impossible to say what’s realistic. We know more about deep space.” OK, Tourette syndrome it is.

I wouldn’t get around to writing the golf book for another two years. My debut novella, Music from Big Pink, was published in the winter of 2005. (It was immediately optioned for film and a screenplay was written by Jez “Jerusalem” Butterworth. As of writing, it has not been filmed either. But that is another very long story involving Robbie Robertson, Robert Pattinson, Sam Mendes and many more.) I delivered my second novel Kill Your Friends at the end of 2006 (it was made into a feature film starring Nicholas Hoult and James Corden in 2015. Nine years from delivery to movie: a time frame that seems comically fast to me now) and I finally got to work on The Amateurs in January 2007. And the book flew out. Gary Irvine, the golfer, soon had a brother, a ne’er-do-well amateur gangster (hence the plurality of the title) who gets embroiled in the contract killing of his brother’s wife’s lover’s wife. (Phew!) The book eventually came to be about family and love and infidelity and fathers and sons and a whole lot more.

A few years pass. I publish several more novels: The Second Coming, Cold Hands, Straight White Male. All very different books with one thing in common: they have all been optioned for movies or TV, and films have been made of exactly zero of them. But increasingly, as I travel the world on book tours, meeting readers from Berlin to Birmingham, Sardinia to Skye, one thing is clear. Whenever I meet a proper fan, The Amateurs is always, always their favourite book of mine.

And then, in 2015, a call comes in from Kenton Allen at Big Talk TV. Big Talk are a respected name in British TV, having made Rev, Friday Night Dinner and many more. And Kenton is lovely, a knowledgeable and capable executive. Rather than a movie, we reimagine The Amateurs as a half-hour comedy series, and he quickly does a deal with BBC Two comedy for me to write a pilot episode. Doing the deal and then writing and rewriting the pilot with notes from Big Talk and the BBC’s commissioning editor takes a year or so. Then, this being the BBC, it must go up the chain. Always a nervous time. However...

The commissioning editor loves it!

The head of comedy loves it too!

It goes all the way up to the head of BBC Two, who says … “Golf? What’s funny about golf? We’re not doing this.”

And there goes another two years of my life. Later, I asked what the head of BBC Two’s background was and was told: “history and natural science programmes”.

“And they can decide what’s funny and what’s not?”

“Yep.”

OK then. Glad we cleared that up.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

While I was writing it, Kill Your Friends came out and, to everyone’s surprise including my own, was a bestseller. I went to my publisher Random House to discuss my next book, very much the golden boy.

“It’s about golf!” I said.

Up until that moment I had thought the expression “their faces fell” was just a cliché. I saw it happen in that room in real time. Jaws dropping. Blank stares boring into me. “Ah, well… um,” I said, “it’s about contract killing and drug dealing and infidelity and golf.”

Much nodding and smiling and normal service was resumed.

The Amateurs came out in the spring of 2009 and did fine. Not quite the giddy heights of Kill Your Friends, but fine. However, the letters I received from readers spoke to a great affection for the novel. The man who was nearly thrown off a flight because he was laughing so hard. The wife complaining that she couldn’t get to sleep for her husband’s laughter rocking the bed. Even the unhappy customers were funny: the elderly man who became so enraged at Gary’s Tourette-laced profanity that he “attacked the book with scissors and threw it in a skip so that no one else could ever read it”. He had clearly forgotten Random House’s insanely capitalistic practice of printing more than one copy. And then, a few months after publication, the phone rang: an offer from the production company Anonymous Content in Los Angeles to option The Amateurs for a feature film and for me to write the screenplay. Anonymous Content were hot, coming off the back of a big critical and commercial hit a couple of years previously with The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Perhaps they saw this as the sporting equivalent? Whatever, we were off. Apparently, Jim Carrey might be a good fit as Gary.

Fantastic. Me and Jim on the red carpet in front of Grauman’s Chinese on Hollywood Boulevard. This time next year, Rodney…

Smash cut to...

A year later. The summer of 2010. I’ve delivered a draft of the script and differences of opinion are beginning to emerge. The executive in charge (I’m not being coy here – I’ve genuinely forgotten their name. They left the company long before we got to the end of the project) is now seeing it very much as a sporting triumph movie. A zero to hero deal. They want to exorcise all the brother/gangster/drug dealing stuff. And I love all that stuff. What we’ve fallen into here is a classic movie business case of “we bought some bananas and now we’ve decided we want some oranges. Can you turn these bananas into oranges?”

Well, we can try. But they won’t be very good oranges.

I spend another year and a couple more drafts trying to perfect their banana-orange before everyone loses interest and they finally let the project drop and give us the rights back. Still, we got paid.

More years pass. More novels are written and published: The Sunshine Cruise Company, No Good Deed. (The former optioned for film, the latter TV. Both very un-filmed as of writing.) Kenton, God bless him, hangs in there and gets another deal together.

At one point he has a fabulous Scottish cast coalescing around the project, including Martin Compston, Dougray Scott and Peter Capaldi. Surely, I think, some Scottish broadcasting entity will take a swing at this. But everyone passes and I am powerfully reminded of Frankie Boyle’s adage that most Scottish film and TV entities exist “solely to ensure that no film or television work ever emerges from Scotland”. I’m also mindful of a problem we’re increasingly facing. The book is not based on a well-known cartoon character or a previously loved fable. There are no men in tights. In a world only hungry for the familiar, The Amateurs is looking like that craziest and most unfamiliar of things: a story someone just made up. You know. Like Alien. Or The Godfather. Jaws. American Psycho. All that mad, uncommercial stuff.

Another year or two passes before Kenton throws in the towel for good and we get the rights back once again. It’s now 2023.

My daughter Lila was just born, a tiny baby, the year I delivered the novel. She is now 15.

My UK agents Curtis Brown mention in their monthly newsletter that the film rights to the book are available once more. We quickly get several calls wanting to do a deal. But leading the pack are an LA company called New Republic.

An independent film financier set up by producer Brian Oliver (Black Swan), New Republic have had a hand in Rocketman and 1917. The executive there who wants to make The Amateurs is a guy called Matt Quigg. He asks how I would feel about setting the movie in the United States rather than Scotland? I say I’d feel great about it. If all the family dynamics and relationships stay the same, this wouldn’t be that difficult.

And besides, it feels as though the time of golf as a subject for the screen is really dawning over there: Netflix’s Full Swing is into its third season. Apple TV are about to launch Owen Wilson’s Stick and there is much gathering hysteria about the forthcoming Happy Gilmore 2. So how do I feel about setting it in the USA? I feel fine.

I was 38 when the idea for the book occurred to me. I am now approaching 60

I was 38 when the idea for the book occurred to me. I am now approaching 60

It is April 2024 when we agree to work together. The lawyers go off to get into the deal – this can take months – and I begin reimagining the whole thing in America. I’m thinking small town Georgia. Maybe Florida.

The months pass. And pass. And pass. As the summer of 2024 comes and goes, it becomes clear things are getting sticky on the business affairs end. New Republic’s lawyers are asking for paperwork to prove that Big Talk – and the BBC – will make no future claims on any movie made from material they had funded a pilot script for.

A situation develops where the three sets of lawyers (New Republic, Big Talk, BBC) are going back and forth, back and forth without being able to agree. From a layman’s point of view, it is impossible to say whether New Republic are being unreasonable in what they’re asking for or Big Talk/BBC are being unreasonable in not providing what New Republic are asking for. To me, it feels as though I am drowning in a sinkhole while three sets of lawyers stand around the edge and argue.

As Christmas 2024 approaches, I am in Los Angeles on other business. I get in touch with Matt Quigg, who suggests we go and play golf with Brian, who owns the company. On the golf course they apologise that the deal is taking so long and assure me it will be done soon. All good. There’s just one worrying thing.

My American friends, I notice, use the “American” scoring method on the golf course. Which is to say, there is many a “breakfast ball” and a “mulligan”. This simply means not counting the shots you don’t like. It is as efficient a way to improve your golf score as has ever been devised and is favoured by the likes of Donald Trump. If you tried it on a golf course in Scotland, you’d soon be digging a putter out of your skull. Still, I reason, a lot of Americans do this. Oh well. But a tiny voice in my head I am trying not to listen to is saying: “Do you really trust these guys?”

I fly home. Christmas comes and goes. As does the winter. We are into spring – and just past the first anniversary of agreeing to work together – when we hear that Matt Quigg has been fired. Once again, the project has outlived the executive who initiated it. In fact, in this case, doing the fucking deal has outlived the executive. And still the three sets of lawyers argue on as the summer of 2025 approaches. Finally, in July, 15 months after I had my first meeting with New Republic, my agent receives a curt communication from their lawyers saying: “We will no longer be proceeding on this.”

Game over. See you later, Sooty.

Amid the rage that envelops me, I have a clear thought: the New Republic lawyers will have billed far, far more hours on negotiating a deal that never happened than I would ever have been paid to write the screenplay. But lawyers only act on instruction from their clients. Why did Brian Oliver kill the deal after 15 months of discussions? Who knows? He vanishes, refusing to answer emails. I go under in the sinkhole, the watery shapes of the three sets of lawyers gradually vanishing from my gaze.

I think again of Lila. She is 17 now and entering the upper sixth. I was 38 when the idea for the book occurred to me. I am now approaching 60. I am bringing all my four children up to speed with the history and the intricacies of the deal so that, when I die, they will be well placed to take over negotiations.

Stay strong and healthy, kids. Bring it home for your old dad.

There is a postscript.

A couple of weeks after all this goes down, I am in the clubhouse of Kilmarnock Barassie, my home course back in Scotland. I’m eating lunch with my friend Graham after playing a brisk 18 holes when a golfer approaches me.

“You’re the writer fellow, aren’t you?”

I confess that I am.

“You nearly killed my friend.”

“Excuse me?”

“He was in hospital recovering from heart surgery and I gave him a copy of The Amateurs. I’m no kidding, swear to God, he ended up laughing so hard he burst his stitches! They had to take him back in.”

“Jesus Christ. Is he OK?”

“‘Oh aye he’s fine, son. Funniest book he’s ever read in his life.” He walks off. Turns back. “Hey, it’d make some film, so it would.”

Yes. I think it would too.