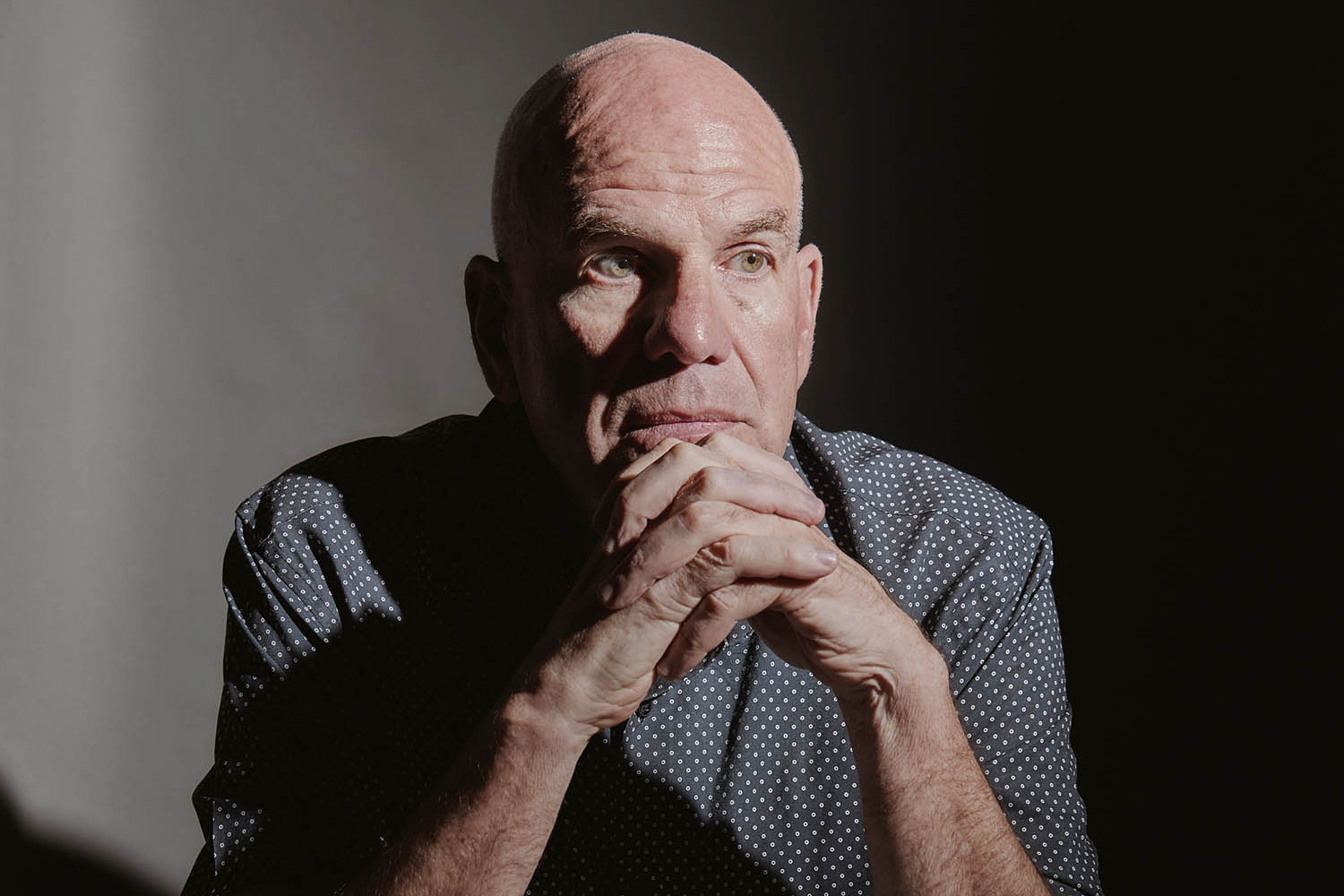

Portrait by Justin T Gellerson

“I can’t get anything made now.” Did I hear that right? Did David Simon – the great television auteur, co-creator of The Wire – just tell me he can’t get a new show commissioned at HBO, his creative base of 25 years?

“I’ll never write anything that’s going to be a franchise,” says Simon. “I was having lunch with the boss there and I said: ‘You know, I’m not sure you guys are the home for what I do any more. You’re not going to take the David Simon Harry Potter miniseries about a bureaucratic Hogwarts that can’t function.’”

It doesn’t sound likely, I concede. But it would make for an entertaining spectacle. To his credit, Simon tells me with a smile, the nonplussed executive did concede such a show would be interesting, if nothing else.

If we’re unlikely to ever have our screens blessed with a streetwise Dobby or tenement-dwelling Weasley family, it remains true that no other TV writer or showrunner has managed to better Simon when it comes to exposing the brokenness and venality of the systems that shape our lives. For its millions of diehard fans, The Wire is the greatest television show ever made, an opinion supported by a legion of critics. Along with The Sopranos, it is the only series I have watched in its entirety three times.

I’m spending a summer morning with Simon, 64, at The Observer offices in London. Having started out on a roof terrace, we are forced by the broiling sun back into the newsroom, a setting he seems to enjoy. The notional reason for our meeting was a new two-year deal he had signed with HBO that guaranteed it a first look at his ideas. Trade press coverage of the news emphasised the depth of Simon’s connection to the network, which began in 2000. The truth is, I have been looking for a reason to meet him for ever.

Simon has come to our interview in sensible denim and trainers. It isn’t work that has brought him to the UK. He is on holiday with his teenage daughter, who has dragged him vintage shopping on Brick Lane in east London. Simon was once called “the angriest man in television” by the Atlantic, and has repeatedly declared that anything good in his life and career has been motivated by an unquenchable sense of personal grievance, particularly his unhappy departure from the Baltimore Sun, where he had worked as a reporter from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s.

But despite this history, and the intense, frequently depressing nature of our conversation, he is remarkably sanguine over the three hours we spend together. The Simon in front of me is a surprisingly soft-spoken figure, pessimistic about the future of the television industry and his place within it.

The Wire aired between June 2002 and March 2008. It told the epic story of modern Baltimore – a city undone by disinvestment and industrial decline – and of the pointless drug war it was, as a consequence, doomed to wage in perpetuity. But labelling The Wire a crime show is like recommending Moby-Dick as a fishing manual. In an extraordinarily layered portrait of institutional failure, no one was exempt from criticism. All the Pieces Matter, as the suave murder cop Lester Freamon, played by Clarke Peters, reminds his colleagues in season one.

Wendell Pierce and Dominic West in The Wire

Over the course of 60 episodes, the viewer was inducted into the dysfunction of the homicide squad and ruthless drug gangs alike, as well as the city hall, Baltimore’s declining dockside unions, the defunded city school system and an increasingly resource-starved news media. It gave us a raft of unforgettable characters, from Omar, the terrifyingly charismatic gay stick-up artist played by the late Michael K Williams, to Stringer Bell, the methodical drug boss with a penchant for the economics of Adam Smith (a career-making role for the then unknown Idris Elba). Nothing on TV had matched its depth and sophistication – and nothing has since.

The show was the brainchild of Simon and his longtime collaborator Ed Burns, a former infantryman, Baltimore murder detective and public school teacher –in that order. It was followed by Generation Kill, a seven-part miniseries based on the reportage of the late Evan Wright, who spent two months with US marines during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Then came Treme, a paean to the post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, and Show Me a Hero, starring Oscar Isaac as an ambitious young politician in 1980s Yonkers.

Simon’s most overtly starry offering, The Deuce, co-created with the novelist George Pelecanos, another longtime collaborator, explored the seedy origins of the 1970s New York pornography industry. It brought a career-best turn from Maggie Gyllenhaal, but never made it past cult status. In 2020, HBO released The Plot Against America, Simon’s six-part adaptation of Philip Roth’s 2004 novel about a celebrity, fascist-leaning demagogue elected US president.

I wonder if Simon ever grew tired of the keen attention lavished on The Wire in comparison with all that followed. “Look, I don’t say this too often. It turned out very well. But the work I did after was much more mature [and] confident, and very specific to political arguments. The Plot Against America was about [Donald] Trump. It was about the rise of authoritarians. Those pieces are shorter and more ambitious, in many ways.”

Simon was raised in suburban Maryland by his father, Bernard – a thwarted newspaperman who spent 20 years working as PR director for B’nai B’rith International, a Jewish-Zionist nonprofit – and his mother, Dorothy, a housewife, who later trained as a crisis counsellor and therapist. In this intellectual, robustly competitive household, debate was a family sport. The youngest of three siblings, Simon soon learned to forcefully get his point across. “I was the runt. [So] I had to hang at the edges. Friday night dinners were a lot of fun,” he recalls. The pattern of his career set in early. “I edited my high school paper. A biweekly little rag. I published something that pissed off the administration. They were furious with me.”

Simon worked as a stringer for the Baltimore Sun while attending the University of Maryland, becoming a staff reporter after his graduation in 1983. He quickly found himself on the crime beat. “I hate that nostalgia shit, because people are still engaged in that fight, but I do feel like I caught the tail end of the moment [of] newspapers, at least the local ones.” Simon met Burns – then a bookish, rather arrogant murder detective – in 1984, while reporting on a wiretap investigation into a Baltimore drug kingpin called Melvin Williams (the case would inspire The Wire, in which Williams made sporadic cameos as the Deacon, a local pastor and community organiser).

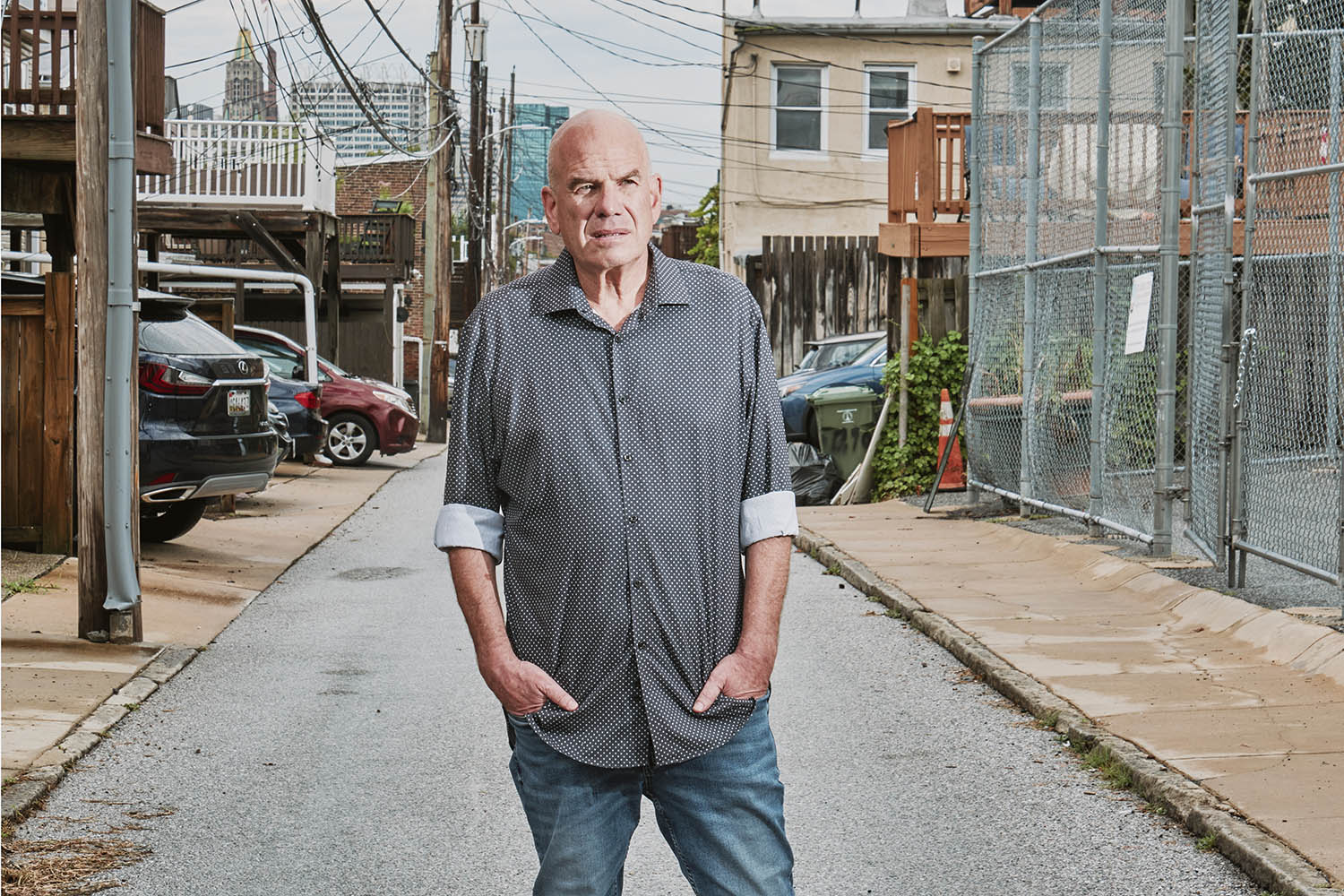

David Simon photographed for The Observer in Baltimore

In 1988, Simon spent a year shadowing Baltimore murder detectives as they went about their business in a city – with a population back then of roughly three-quarters of a million – that saw more than 200 murders a year. The resulting book, Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, contains the themes and concerns Simon would return to in his TV career. The officers, and the criminals they hunt, are depicted by Simon as good, bad and indifferent; capable of extraordinary bravery and corruption, sometimes within the same night shift.

They preside over an inner city forgotten by the rest of the nation, its people and landscape objects of pity and terror to those outside it. The truth is that “everyone lies”, Simon writes: “Murderers lie because they have to; witnesses and other participants lie because they think they have to; everyone else lies for the sheer joy of it, and to uphold a general principle that under no circumstances do you provide accurate information to a cop.”

As a broke postgraduate student in the east end of Glasgow, I’d taken out a copy of Homicide: A Year on the Killings Streets from the local public library. Over several unusually balmy days, I found myself engrossed in what is one of the most powerful, and original, works of late-20th-century American reportage. This was how to do it, I remember thinking. That I barely knew what it was hardly mattered. I was hooked.

The way Simon has always told it, his move into TV was a reasonably happy accident. His agent had little joy shopping Homicide around producers. When Simon suggested that Barry Levinson – the Oscar-winning director of Rain Man, who was also from Baltimore – might be interested in taking it on, it was in jest rather than expectation. But Levinson, who had a deal with NBC to produce a pilot based on material of his choice, was hooked too. Homicide: Life on the Streets began airing in 1993 (it would run for seven seasons until 1999). The timing was propitious. After a round of buyouts, life at the Baltimore Sun had begun to feel untenable under an “out of town” ownership that had little interest in anything other than maximising profits.

“It was a family-owned newspaper,” says Simon. “It wasn’t public. [They] then noticed they could make a lot more money putting out a shittier newspaper with fewer staff in a smaller newsroom. The failure of journalism had nothing to do with the internet; it was about greed and short-term profits.”

His loathing of the term “Dickensian” – a description that has often laced critical discussion of The Wire – stems from a particularly irritating editor from that period; a figure who insisted the paper’s reporters focus on journalism about prize-friendly fables of charming drug addicts and poverty stricken children in various stages of photogenic distress.

Simon took redundancy in 1995. He was invited by executive producer Tom Fontana to join the writing staff on Homicide. “[Tom] let you do everything. Not all at once, but first he’d send you to set. Then it was local casting for the day players. Then he’d bring you into editing. And then he’d have to do it all [again] because he was better at it. The truth is that he built us, so we could go out and sell our own stuff.”

We once had a two-day argument about what Stringer Bell’s countersurveillance method was going to be

We once had a two-day argument about what Stringer Bell’s countersurveillance method was going to be

In the mid-1990s, Fontana showed Simon early cuts of his dark prison series Oz, one of HBO’s first forays into what would become known as “prestige TV”. The experience was revelatory. HBO made its money from subscribers instead of advertisers; this, Simon realised, enabled the creation of the sort of long-form stories that would, until then, have you laughed out of a network pitching meeting.

The phrase “the golden age of American television” usually refers to the extraordinary creative flowering that took place at the turn of millennium, when The Sopranos, Deadwood, Mad Men, The Wire and others pushed the form into uncharted waters. They presented complex, morally compromised characters doing horrible things in grimly realistic fictional universes. Some seasons ran to 13 episodes and built up slowly, demanding patience from their audience.

In his 2013 book Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution, the journalist Brett Martin explores the careers of the stubborn middle-aged men behind this revolution. In his telling, David Chase of The Sopranos, a self-loathing jobbing TV writer and thwarted avant garde film-maker, fired one of his writing staff the day they received an Emmy nomination. David Milch, the creator-producer of Deadwood, a hardcore gambler, took to dictating lines off-the-cuff to frazzled actors on set, when he wasn’t pissing out of windows, or handing out wads of cash on the street. Simon, in comparison, looked rather well behaved.

The Wire was not an overnight success. It was in fact, at first, a steaming failure, at least in terms of ratings or awards, at the constant threat of cancellation throughout its years on air. If The Sopranos could command 10 million viewers an episode, The Wire hovered at about 3 million for most of its run. But the rise of the box set (by the late 2000s, no self-respecting middle-class home lacked The Wire on DVD) meant people could come to it at their own pace. And they did – in their droves.

Considered from the rear-view mirror, this “golden age” was surprisingly brief. And nothing feels quite so alien as the day before yesterday. The rise of the big tech streaming behemoths has done for television what corporate raiders did for the broadsheet newspaper. “Everyone has been making more television,” says Simon. “A lot of it was very good and varied. And a lot of it was shit. Probably about the same [as] it’s ever been.”

The problem, he says, was that costs ballooned. And – much like in his previous journalism career – the moment arrived when the moneymen realised they could trim budgets and fatten profits. The short-sightedness of this, as Simon has put it, is self-evident. Where, he has asked, were the new generation of showrunners likely to come from in an increasingly precarious industry? “The streaming bubble burst … I don’t know how you build a brand. [But] there are three things that will fuck up any chance of quality storytelling: fear, greed and the hunger for repetition.”

Certainly, it appears that the days when a Chase or Milch or Simon would be granted autonomy to create multiseries dramas are over. Does he, I ask, think The Wire could be made today? There are better examples, he suggests. “Think about what it must be like to walk in and pitch something like Treme now. Carolyn Strauss, my boss at the time, said: ‘I have no idea what you’re talking about. Just go and make the show.’ Can you imagine that environment today?”

I can tell Simon feels wounded by his bracketing with Milch and Chase in the category of the difficult auteur. Though he admires both men, he is keen to stress that his long-term producer, Nina Noble, would never have tolerated any of the behaviour associated with Milch.

“If I sent pages down to set on the day I wanted them shot, she’d kill me. She’d [have] had a teamster beat the fuck out of me in the back alley,” he says.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Simon has never sought to take anything like full credit for The Wire, or any of the rest of his shows. Showrunning involves the managing of actors and writers alike, two constituencies hardly famed for their lack of ego. “Ed [Burns] could be unrelenting. We once had a two-day argument about what Stringer Bell’s countersurveillance method was going to be. Would he be buying a new cellphone every day, or just replacing the interior mechanism? We lost two whole days in the writers’ room to that. There were people who wanted to kill us in that room – for good reason.”

Still, false modesty is not an affliction that plagues Simon. It wasn’t just lingering memories of a tedious ex-editor that made Simon reject the Dickensian line. There are, he has said, many better and no less lofty comparisons available – Balzac and Tolstoy, among them. To invite these comparisons takes a specific kind of chutzpah. But then, few other TV shows have been taught to undergraduates at Harvard, or boasted literary novelists such as Richard Price (Clockers, Lush Life) on the writing staff.

At some point in our conversation, I know I am forced to contend with the fact of Simon’s online presence. And it is an awesome thing to confront. Simon joined what was then Twitter in August 2012; over the intervening 13 years, he has cultivated a style of posting that resists categorisation. Veering between heavily muscular irony and crushing earnestness, his approach is to grind his enemies into the digital dust. Compound swearing abounds. Adversaries are “slugfuckers” and “shitcrests”, or “fuckmooks” and “scroterash”. Or “shitecrisps”, “fuckfails” and “shitfesters”. Or “scrotelicks” and “fuckpecks”. This is by no means an exhaustive list.

The targets of Simon’s ire range from Donald Trump (“an empty-suit, race-hating fraud”) to graduate students with a few hundred followers, who quibble with his views on the Middle East or American municipal politics. Simon’s formula for troll management, he has declared more than once, is simple. Mock, block and roll.

There is no doubt that an appreciative audience for this kind of thing exists – just as there are people who enjoy watching Formula One. I am not one of them. When I first discovered Simon’s Twitter in the mid-2010s, I found it extremely dispiriting that the mind that had produced Homicide, The Corner, The Wire and Generation Kill was spending what seemed to be an incredible amount of time arguing with random no-marks. Did he ever think about toning down some of his more bullish social media output?

“Not really,” Simon replies. “I do have a lot of fun presenting as the voice of insincere and caustic argument. But that’s all a little sideshow. It’s performance art.” I was, however, reminded of the famous pan of the Martin Amis novel Yellow Dog, in which the reviewer likens the experience of reading it to catching your favourite uncle masturbating in a playground.

Winona Ryder in Simon’s HBO miniseries The Plot Against America

This is not a Simon specific problem, the central horror of existing online: it makes addicts of us all. Still, what is appropriate for a Trump-bashing zinger seems wildly out of whack when deployed against arguments about Israel’s massacres in Gaza: is it edifying to respond to those engaging in that debate as “shitheels” and “shitmongers”? Like most people, Simon is less crass in real life. “The truth is that these are two wounded peoples with extremists on both sides holding the mass of Arabs and Jews hostage,” he says.

The only time I sense irritation on Simon’s part towards me during our morning together is when we are discussing the efficacy of slogans such as “Defund the police.” For him, such statements only risk alienating people, a point I’m not sure we disagree on. “Anyone who has simple solutions to complex problems is probably fucking you up,” he says, with what I sense to be a new briskness in his tone. “You can accuse me of being a centrist or police apologist. You can and it’s fine.”

Towards the end of our time together, we arrive at The Deuce. Despite its A-list cast and lavish budget, it never really erupted into the mainstream. Some of this could be perhaps explained by the grimness of its topic, though not all. In January 2018, its lead actor, James Franco, was accused of inappropriate behaviour by five women, four of whom had been students at his New York acting school. The allegations included being pressured into nudity and that Franco had violated their boundaries during sex scenes. A lawsuit was settled for $2.2m in 2021 with the actor subsequently admitting to sleeping with students, behaviour he conceded was “wrong”.

Simon’s initial response had been to rail against the Los Angeles Times, which broke the story, and to draw a distinction between Franco’s alleged behaviour and the crimes of disgraced producer Harvey Weinstein. Simon said in Rolling Stone that the allegations were “hyperbolic, because on a very basic level, what James is dealing with – and it’s meaningful – it’s not what we’re seeing in the other cases involving #MeToo. It simply isn’t.”

Does he still believe that, I wonder?

“There were things [for] which he owed a certain amount of self-reflection and apology,” Simon says carefully. “And I would say they involved being absolutely and blissfully unaware of the power of being James Franco.” Though he believes Franco should not have had relations with any of his students, Simon argues that it “isn’t the same as: ‘[If] you want this part...’” They would, he continues, have shut the show if that line had been crossed.

Before he leaves, Simon tells me that though he’s broadly happy with his lot, there are many more shows he hopes to make. “You know, I’m 64. I had a good 25-year run. But on my shelf, there is [still] a series about the history of the CIA and American foreign policy since the second world war. There’s a miniseries about the first Muslim FBI agent and how he got run out of the bureau. There’s another piece [about] child protective services and the family courts. There’s a punk musical using the music of the Pogues.”

The only problem is finding a loving home.

Photographs by Justin T Gellerson, Alamy