Photograph by Christian Witkin for The Observer

In the director Noah Baumbach’s new film, Jay Kelly, a generational movie star in the twilight of his career finds himself short on second chances in his personal life. Jay (George Clooney) travels to Italy to receive an honorary award at a Tuscan arts festival, but the only person still by his side for the video montage of his greatest hits is his long-suffering agent Ron (Adam Sandler).

In September, Baumbach himself travelled to Switzerland to receive an honorary award at the Zurich film festival for his contribution to cinema. There, at a convention centre perched on the tip of Lake Zurich, he watched a video montage of his greatest hits. Beside him was just his publicist, Liz. “She made it with me the whole way,” he says with a laugh.

Baumbach, 56, has made darkly funny, troublingly relatable films about interfamily warfare and reluctant comings of age that include Greenberg, The Meyerowitz Stories and Frances Ha. In Zurich, he wasn’t watching himself on screen, but it felt like a record of his life: the armies of people who had been assembled and collapsed to make the films in each clip; footage that documented a specific moment in time that was emotional to witness. He hadn’t watched some of the films in so long that he didn’t see all the detail you notice from up close, but instead recalled the day they shot that scene and the people who were with him. It was a feeling he had already captured with a line that Clooney delivers a little ruefully in Jay Kelly: “All my memories are movies.”

For so long, Baumbach’s work has reflected his personal life – his parents’ divorce in The Squid and the Whale, his own divorce – from his first wife, the actor Jennifer Jason Leigh – in Marriage Story, and now, here life was reflecting his work back at him. “It’s like with kids – you turn around and they are suddenly older,” Baumbach says in his living room in south-west London. “Ultimately, I feel proud of what I’ve done and I’m glad they are out there like some alternative version of me and my life.”

If this sounds a little sentimental for the writer who has made cynicism and narcissism a seemingly bottomless well in many of his characters, then Jay Kelly is just such a departure.

I had arrived at Baumbach’s house on a glowing October afternoon to an uncarved pumpkin by the front door and his small, scruffy dog, Wizard, pinging around the hallway. It was the day before Halloween; Baumbach was not dressing up but his two young children would be Robin Hood and a snail. The house, which has a postcard view of the rolling vista that JMW Turner once painted, seemed to have suffered an explosion of stuff, with rows of children’s shoes and toys along the hallway. Baumbach apologised for the chaos, which included half-assembled moving boxes sitting expectantly, explaining that the family would be moving back to New York in a few weeks.

Surrounded by small stacks of books in every corner, he sat with his arms folded behind his head and spoke in long sentences that seemed to keep closing in on what he thought, before retreating a little. “I wasn’t interested in telling the story of a movie star looking back on his life and coming to terms with his failures and successes, I mean, in and of itself…” he says. “I saw it as a way to tell a story about trade-offs and about mortality.”

Jay Kelly is the story of a man with less road in front than in the rear-view mirror, haunted by a past that visits him in ghostly memories. In the film, which Baumbach co-wrote with Emily Mortimer, Jay has sacrificed friendships and family in order to become Jay Kelly. He is a Dior ambassador with a private jet who can’t remember if he even likes the cheesecake that has ended up on his rider, and which now follows him around the world. Everywhere he goes, strangers fawn over him and staff on his payroll laugh at his jokes, while his daughters and childhood friend shrink away from him.

Someone recently pointed out to Baumbach that many of his films are the stories of people who didn’t become what they wanted to be, and how that failure has defined them. In this case, Jay Kelly became everything he wanted to be, but he has started to wonder who that person actually is. “I think the older one gets, you realise: OK, I’ve been doing it this way for a while. Is this really the way I want to do it?” Baumbach says. “I mean, do I like cheesecake or do I not like cheesecake?”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

For the past two years, Baumbach, his wife, Greta Gerwig, and their two children have been living in London while she directs a Netflix adaptation of The Magician’s Nephew, from The Chronicles of Narnia by CS Lewis, and he made Jay Kelly. Over the years, Gerwig has appeared in a handful of Baumbach’s movies, most notably as the freewheeling protagonist in Frances Ha. He also credits her as a great influence on his writing behind the scenes, saying: “We’re always very involved with each other’s stuff.” The family lived in London while making Barbie – a film they wrote together, and Gerwig directed, and that made more than $1.4bn globally. Working on Barbie re-energised Baumbach after the difficult slog of White Noise, the ambitious 2022 adaptation of Don DeLillo’s novel that he had long wanted to make, but was not warmly received.

Jay Kelly has been a similar balm. While shooting, Baumbach has been able to wrap filming at 6pm, drive the half-hour home from Shepperton studios in Surrey and be back in time to put his kids to bed. “It was really wonderful, as opposed to movies where you’re shooting into the night. You come back and everyone’s asleep and you get up before they do,” he says. “We are all a bit melancholy at the thought of leaving.”

Baumbach describes his work as “personal, not autobiographical”. Jay Kelly is not about divorce per se, but it is clearly the work of someone who has known separation from someone with whom they share a child. (Baumbach has a son from his first marriage to Leigh.) The film finds Jay physically searching for his younger daughter Daisy (Grace Edwards), whom he follows on a European road trip to try to make up for lost time before she goes to university. He’s also reaching for his estranged elder daughter, Jessica (Riley Keough), with whom his time might already have run out. Was the idea of fathers who work in the film industry not being around – also a theme in Joachim Trier’s 2026 Oscar contender Sentimental Value – reflective of his own life?

“No. I mean, yes and no. I don’t feel like Jay Kelly at all, but no matter what, there are trade-offs and things that we are…” he trails off. “Choosing anything means not choosing something else.”

I ask because Jay Kelly, like several of his films, suggests that the children of artists have a hard time, an experience that he seems to understand from both vantage points. “I grew up with creative parents, so I’m familiar with that struggle,” he says, explaining how this idea is expressed in his 2017 film The Meyerowitz Stories, in particular by the sense of “art being religion” – that “if you’re not an artist, you’re somehow not in the fold”.

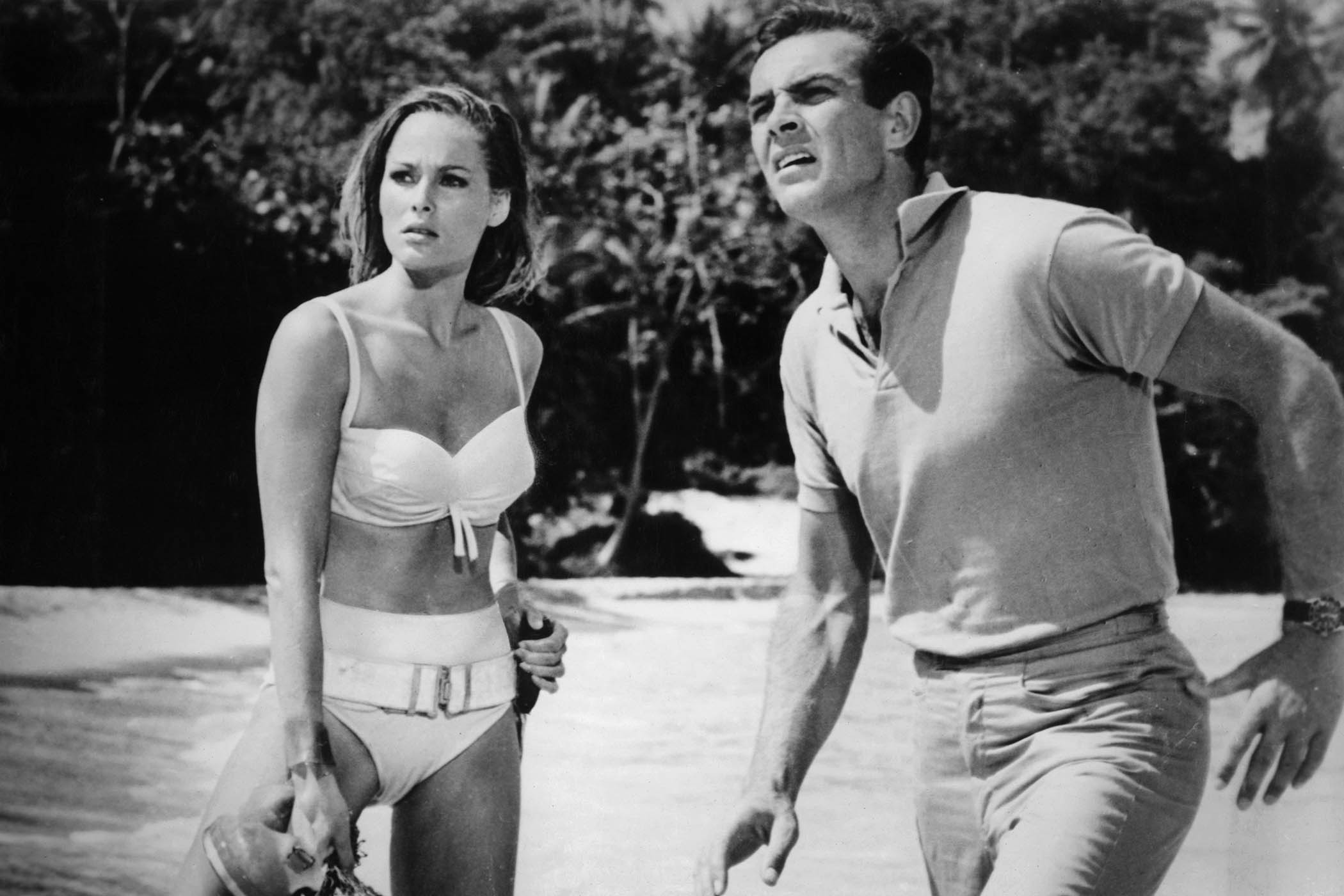

George Clooney as Jay Kelly and Adam Sandler as Ron Sukenick in Jay Kelly

Baumbach’s parents were both writers: his father was the author of 12 novels and ran the creative writing master’s programme at Brooklyn College; his mother wrote fiction and worked as a film critic for the Village Voice. Baumbach recalls the thoughtful dissection of culture as the shared family sport. “If we all saw a movie, it was like the talking about it would be part of it,” he says. “If we didn’t love it, we’d come up with a better ending or some way to improve or recast it.”

One example that stays with him is seeing the 1985 film Year of the Dragon, directed by Michael Cimino, which his father believed should have ended at an earlier point. “It was cutting 20 minutes out of the movie, but it would have left it totally open-ended. I remember thinking: ‘That would have been a great ending.’” This way of being able to talk authoritatively about art was seductive, Baumbach says, and it introduced him to so many films and books that formed part of his cultural education. “It did carry a burden, though,” he says. “Feeling like you know how you’re supposed to think about something before you’ve actually even had the experience.”

The experience of being treated as an adult when you’re a child, or of behaving like a child when you’re an adult, recurs in Baumbach’s work, where characters drag their heels about growing up and young children often seem like the most stable people in the room. In Greenberg, Ben Stiller’s titular misanthropic wash-up delivers a line that could be the tagline for Baumbach’s body of work: “It’s weird ageing, right? It’s like: ‘What the fuck is going on?’”

With Jay Kelly, Baumbach wanted to depict someone who, despite their age, is only just realising life is finite. “There’s certainly that feeling when we’re younger that we have time to get to the other things; that choices can be temporary, or they’re bargains that seem reasonable,” he says. “Jay is realising this is the one time.”

A few weeks after seeing Baumbach, I take the lift to the third floor of a London hotel. Inside one of the rooms, I find Clooney and Sandler watching the changing of the guard through a rain-streaked window. “They’ve already got the guard – why you gotta change it?” Clooney cries dramatically. The pair are in town for a run of interviews, screenings and dinners to promote the movie, clearly exhausted but both wisecracking to the amusement of the other.

“Can’t complain,” Clooney says. “Well, I can complain.”

“You choose not to complain, I notice,” Sandler replies.

“I’ve decided not to. You complain enough for both of us.”

“I really do,” Sandler groans. “You’ll see.”

Clooney was one of only a handful of actors Baumbach and Mortimer felt could play Jay Kelly because of the in-built relationship the audience already have with his work. But Clooney, who had especially admired Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories, knew his role was a challenge. “When I read it, I thought the character was a dick,” Clooney says. “Everyone loves him except his family and his friends, and that seems like a pretty awful existence.” The trick, he says, was to let the audience see him through the loving eyes of Ron, wherein they could “believe there’s something worth saving in this guy”.

Sandler has proven that he is more than capable of turning in a brilliant dramatic performance, channelling mesmeric energy in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love in 2002 and, 17 years later, in the Safdie brothers’ Uncut Gems. Still, there were emotional depths he had to plunder to play Ron that worried him. “When you read [the script] and see ‘heavy sobbing’,” he says. “I don’t know about anyone else but I don’t know if I can pull that off.”

For both actors, Baumbach’s guidance was crucial to overcome these obstacles. “I’d say every scene, he’d tell me something that made it click what my character was thinking or going through, or what the scene was really about,” Sandler says.

“Sometimes, there was just a disappointing look,” Clooney says. He laughs: “We’d do a scene we thought was really good and he’d just have that sad look on his face.”

Baumbach is known for shooting many takes. Earlier in his career, he kept a tiny crew and tight budgets on films such as Frances Ha and Mistress America, in part so that he had the flexibility to do so. Clooney warned Baumbach that he was too old to do endless takes, but in the end did everything the director asked for.

What Clooney realised in making Jay Kelly was that Baumbach knows exactly what he’s looking for. “The directors that I’ve worked with that I really admire the most – the Coen brothers, Steven Soderbergh, Alexander Payne – they all shoot with a point of view. They’re not getting 15 different setups to get in an editing room and try to come up with a story,” Clooney says. “Noah shoots with a point of view.”

There’s nothing wrong with ambition. It’s just knowing what it’s at the expense of

There’s nothing wrong with ambition. It’s just knowing what it’s at the expense of

Sandler, who had previously worked with Baumbach, had already relented to his way of working and had not looked back. “I gave in to him on Meyerowitz and I have not stopped since,” Likewise, Clooney found himself submitting to Baumbach without even realising he was doing so. “All directors lie to actors – the good ones make you feel as if it was your idea,” he says. “He’s very good at manipulating, which is what you’re supposed to do, right?”

Fame, as Baumbach sees it, is no cosmic accident. “You read so many profiles of famous people, and they’re quite ambivalent,” he had told me. “They didn’t get there by accident.” Yet for all the people we see Jay push aside to get what he wants, Baumbach says he wasn’t interested in judging him. “There’s nothing wrong with ambition,” he said. “It’s just knowing what it’s at the expense of.”

I ask whether the film made either actor feel differently about choices between life and work. “My father was an anchorman [a newsreader] and he wasn’t around very much,” Clooney says. “When you’re young, you hold [those] things against people. And then you get a little older, you go: ‘Oh, they were putting food on the table.’”

“There’s no way to do it right,” Sandler says. “Any way you go, you can look back and say: ‘I wish I worked harder at my craft, or I wish I was with my family more.’”

I recalled Baumbach saying that if anyone hangs around for long enough on his sets, he’ll usually end up finding a part for them. He has been sneaking his own friends and family into his work for years – his grandfather’s paintings or his own books have featured, and a dinner party scene in Frances Ha was shot in his father’s New York apartment. The same was true on Jay Kelly, where, unlike in the story they were telling, Sandler brought his family along, with one of his daughters even playing his daughter in the film.

On weekends, Sandler says he would get calls from Baumbach asking whether he’d spoken to Clooney and what trip was being planned for everyone’s family to get together. “He created an environment where it was so warm with friends and family,” Clooney says. “But I don’t have any family members in it… and I’m a character who doesn’t really have a family and doesn’t care about family,” he says.

“Your security guard was there, though,” Sandler says cheerfully.

In a 2013 New Yorker interview, Ben Stiller, who has appeared in three of Baumbach’s films, used the phrase “A Noah happy ending” to describe the so-so fate that the director often resigns his characters to. That phrase seemed just right to me until I saw Jay Kelly, where the ending, like the film, felt like new territory.

In the final scene at the Tuscan arts festival (if you haven’t seen the film yet, you might want to look away now), Jay watches the montage of his career with scenes cut from clips of Clooney’s actual career. Baumbach had not told them this was happening, so the first he or Sandler knew about it was watching it with a full audience in the theatre. “Watching 40 years of time kind of go by, I think for both Adam and I was emotional because it was literally in the blink of an eye,” Clooney says.

In the film, Jay then looks for the camera and asks to do the scene again, recalling the opening scene, where he wants one more take on set. For all the sentimentality of the movie, it felt like a sadder final note than I had expected. I put this to Baumbach, asking whether it was, as I’d seen it, someone looking back at their life, longing for the chance to correct their mistakes.

“I think people, probably related to where they are in their own lives, can find it more hopeless or less hopeful,” Baumbach had said, not quite closing in on how he felt. “I think it’s about accepting this is how I did it – whether you want to do it differently or not.”

In his experience, asking for another take is something that actors often do when they can feel an evolution in their performance taking place – as though they are within touching distance of somewhere new. “They think: ‘I was feeling a certain thing. I think I could feel it more. I’d like another opportunity,’” he had told me. “We all have those experiences, where we can either explore why something had such an effect on us, or shut it out and go on with life.”

Or perhaps there is another way, as Baumbach has learned: you can always relive it in a movie.

Jay Kelly is available to stream on Netflix from 5 December

Additional photograph Netflix