It is a nearly impossible task: to condense a quarter-century of the world’s cinema into a list of just 25 films; to make a comprehensive judgment on the greatest movies of the century so far. But after a great deal of consideration, debate and angst, we – The Observer’s film critics and arts writers – have assembled a list of which I believe we can be proud.

Is it definitive? Well, that’s the thing about art rankings. They are protean entities that respond to the wider cultural and political landscape. A film that felt essential and of its time when released could be quaintly irrelevant a decade later. There are inevitably multiple omissions (I’m still kicking myself that I somehow neglected to include Edward Yang’s Yi Yi and the peerless masterpiece that is Paddington 2).

And yet, for all the regret over the titles that didn’t make it, there’s something immensely pleasing about a list that includes the lush, shimmering romance and skin-tingling beauty of Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love and the disreputable, debauched comedy of Paul Feig’s Bridesmaids.

It’s a list that embraces challenging, formally rigorous works such as Michael Haneke’s Hidden (Caché), Joshua Oppenheimer’s groundbreaking documentary The Act of Killing and Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, but also makes space for elegantly unexpected genre movies such as Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth.

But here’s the other thing about best film lists: they are part of a wider conversation. Do vote for your favourite on this list in our online poll – or get in touch and let us know what we got right and what we got wrong.

Which of these films do you think is the best of the century so far? Vote on your personal top three here – and tell us what we missed

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-Wai, 2000)

In 1960s Hong Kong, two cuckolded spouses embark on an affair of their own, triggering years of unresolved desire and missed connections. The most purely romantic film of the century is an old-school melodrama elevated by the sensory specificity of Wong’s film-making, imbuing each cigarette, each lipstick stain and each woozy needle drop with palpable, lingering yearning. Guy Lodge

Y Tu Mamá También (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001)

The fuel of Cuarón’s road trip is a desire for sex and adventure that carries two teenage boys from Mexico City to Oaxaca. Tenoch (Diego Luna) and Julio (Gael García Bernal) encourage the older Luisa (Maribel Verdú) to join them, hoping to simply seduce her; instead, she changes how they see the world. The sex scenes, of which there are many, are choreographed with the unselfconscious language of raw hunger for another body – and for life itself. Olivia Ovenden

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

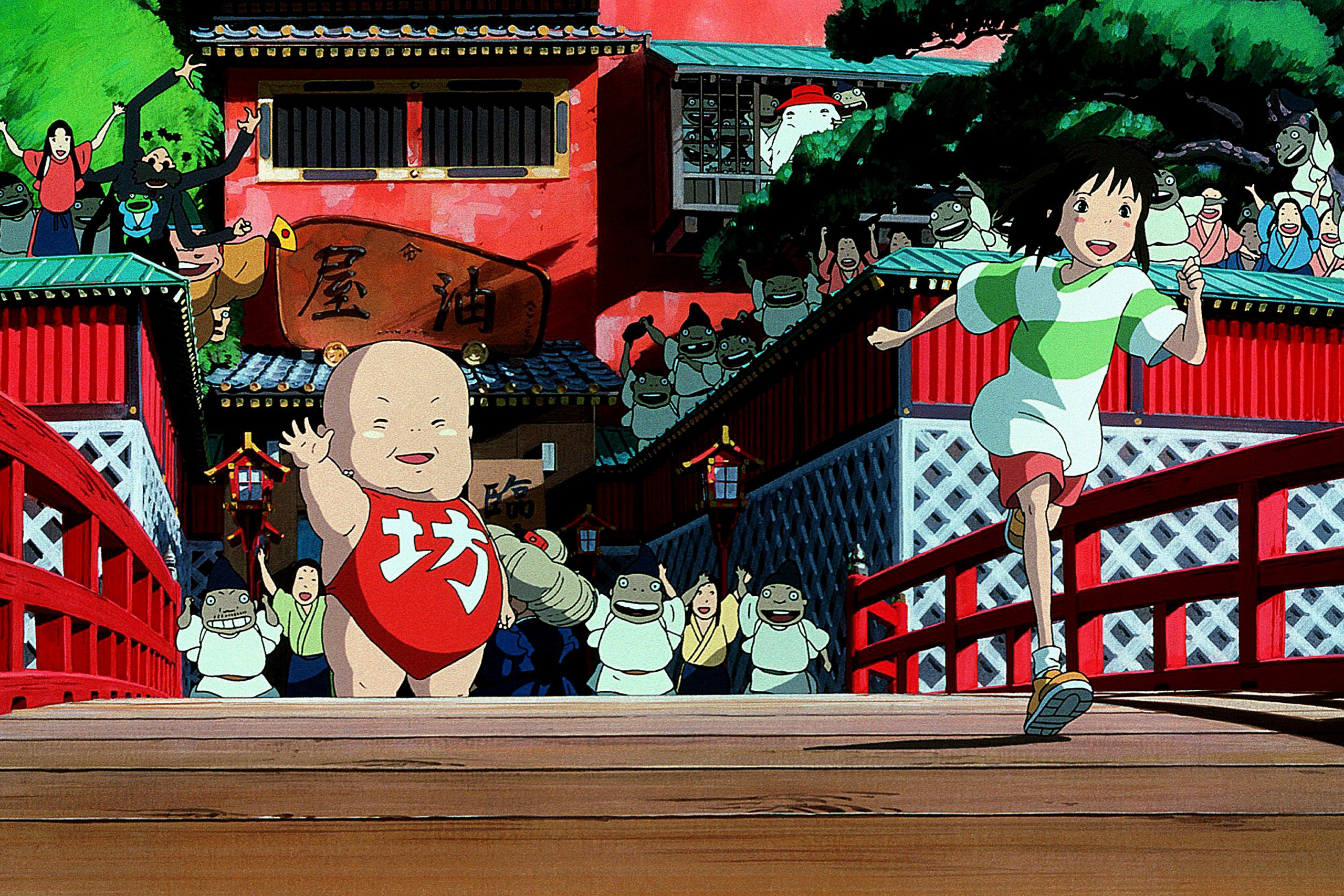

Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001)

A young girl is uprooted from her old life by her parents’ house move, only to be displaced again, thrust into another world, where she must work at a bathhouse run by a witch and her shapeshifting charges, servicing a series of unruly gods. A fever dream of an animation that redefined the storytelling potential of the form, Spirited Away brought the glorious, painterly aesthetic, fantastical world-building and powerful emotional cadences of Japan’s Studio Ghibli to a global audience. Tom Gatti

Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003)

A movie star (Bill Murray) in the whisky advert twilight of his career and a young graduate (Scarlett Johansson) waiting around for her husband find unlikely kindred spirits in one another while staying at the Park Hyatt hotel in Tokyo. Coppola’s emotionally resonant story brings together nights in karaoke bars and surreal meals in a dislocated jumble, evoking the sense of being adrift in a strange place in your life. OO

Caché (Michael Haneke, 2005)

A thriller without a car chase and a whodunnit without a resolution, Caché (Hidden) is a deeply unsettling examination of national and personal guilt. Daniel Auteuil plays Georges, a Parisian TV host who receives an anonymous package: a videotape containing surveillance-style footage of the apartment he shares with his wife (Juliette Binoche) and son. More tapes follow, sending Georges into the past in search of answers – something that this supremely stylish, intelligent film withholds to the last tantalising shot. TG

Pan’s Labyrinth (Guillermo del Toro, 2006)

Part macabre fairytale, part war film and part political allegory, Del Toro’s shiveringly creepy drama is also a bruising account of the end of childhood innocence. The setting is Spain in 1944. A young girl, Ofelia, moves with her mother to live with a cruel stepfather, a fearsome fascist army captain played with beetle-browed savagery by the great Sergi López. Ofelia finds an escape, of sorts, in an enchanted realm beneath the house. WI

There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007)

Though ostensibly based on Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!, Anderson’s portrait of a corrupt prospector riding the California oil boom of the early 20th century felt like a new and immediately canonical American text when it was released in 2007. It is starkly tragic and darkly funny, with an instant archetype of capitalist evil in Daniel Day-Lewis’s utterly possessed performance as Daniel Plainview. GL

Wendy and Lucy (Kelly Reichardt, 2008)

Following Michelle Williams’s homeless blue-collar drifter as she searches for her missing dog in semi-rural Oregon, this shattering miniature is one of several Reichardt films adapted from short stories. As in her best work, it has the concision and allusive depth of that literary form, capturing the spirit of a class and country in one small-scale but penetrating tragedy. GL

The Hurt Locker (Kathryn Bigelow, 2008)

A nerve-shredding combat thriller set among a US army bomb disposal squad working in Baghdad, Bigelow’s lean, forensically observed picture is not just one of the great war films of the last quarter-century, it is also a compelling character study. Jeremy Renner stars as a man hooked on the adrenaline that comes from flirting with death for a living. WI

Fish Tank (Andrea Arnold, 2009)

Raw, ragged and raging: in her second feature, Arnold brilliantly captures the churning conflicts in teenage Mia, the film’s volatile and combative central character. The 15-year-old lives with her hard-partying single mum and younger sister, and her life changes for ever when she meets her mother’s new boyfriend, played by a charming and slippery Michael Fassbender. WI

The Social Network (David Fincher, 2010)

Fincher’s film about the founding of Facebook and the legal struggle that followed is a prescient portrait of the ruthless male egos of the tech world, who, 15 years later, have more power than ever. With an enduringly quotable script by Aaron Sorkin, enabled by stellar performances by Jesse Eisenberg and Andrew Garfield, the movie reframed how we understand Silicon Valley billionaires, right down to their self-consciously casual hoodies and fuck-you flip-flops. Anna Leszkiewicz

Bridesmaids (Paul Feig, 2011)

What to watch when everything’s going wrong? It’s hard to compete with the sight of a woman in a wedding dress, shitting in the street. Fieg’s comedy, starring and co-written by Kristen Wiig, is quite possibly the funniest film of the century so far – thanks to its blend of scatology, silliness and schadenfreude. Wiig is wretched, Rose Byrne at turns serene, demonic and desperate: in this movie, nobody gets to be a princess. Poking fun at an age of hysterical matrimonial excess, its message endures: laugh when the proverbial hits the tarmac. Katherine Cowles

The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, 2012)

A landmark documentary, Oppenheimer’s ingenious meditation on the 1965-66 Indonesian genocide probed both the moral consciences of its perpetrators and the ethics of nonfiction film-making. Directly drafting former executioners of the New Order into re-enactments of their crimes, it is confrontational and cathartic, but hardly cleansing; its understanding of mass-murderer psychology far exceeds the reach or grasp of any Netflix true-crime special. GL

12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013)

The British artist-director won international acclaim – and the best picture Oscar – with this striking adaptation of the 1853 memoir by Solomon Northup, who was abducted and sold into slavery. It’s the disparity between the film’s stylistic grace and the unvarnished realism of its violence that makes this such a disturbing account of the realities of slavery. Chiwetel Ejiofor leads an illustrious cast (Benedict Cumberbatch, Paul Dano, Michael Fassbender, Brad Pitt), with Lupita Nyong’o making an intensely striking debut. Jonathan Romney

Girlhood (Céline Sciamma, 2014)

Sciamma’s moving and atmospheric coming-of-age drama follows Marieme, who lives in a poor neighbourhood of suburban Paris. Isolated and vulnerable, she meets a group of girls who fight, drink, steal clothes and jewellery, and, in one of the most memorable uses of pop on screen, sing to Rihanna’s Diamonds. The director’s complex film-making captures the disorienting time in a girl’s life when she is sexualised by the outside world but still a child inside. AL

Lady Bird (Greta Gerwig, 2017)

Gerwig’s sincere yet funny portrait of a girl in the golden hour of adolescence begins with a universal teenage experience: Lady Bird (Saoirse Ronan) and her mother (Laurie Metcalf) arguing in the car. “I wish I could live through something,” Lady Bird sighs, as her home city of Sacramento rushes behind her. “The only exciting thing about 2002 is that it’s a palindrome.” Ronan and Metcalf give note-perfect performances that blend the comic and the dramatic, while the film’s warm palette and cleverly accelerating pace suggests that we don’t always know we’re experiencing a formative moment until it’s in the past. AL

Zama (Lucrecia Martel, 2017)

The brilliant and often perplexing Argentinian auteur Martel (La Ciénaga, The Headless Woman), detoured into period drama with this adaptation of Antonio di Benedetto’s novel. Set in the 18th century, it follows the misadventures of an official in a remote settlement as he yearns for a better posting and the love of a Spanish noblewoman. With Martel’s characteristic ambience and narrative fragmentation, the film evokes the folly and monstrosity of the colonial project to acerbic tragicomic effect. JR

Call Me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017)

The lure of summer romance consumes 17-year-old Elio (Timothée Chalamet) when graduate student Oliver (Armie Hammer) comes to stay with his family in northern Italy. Their obsessive, tender story – drawn-out afternoons reading by the pool; playful bickering and longing glances; coming together after darkness falls – burns bright but cannot last. The final scene of Elio’s pink, bleary face weeping into the fireplace captures the gut-wrench of a first heartbreak that feels impossible to survive. OO

Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017)

The style and voice of this great American satirical horror is so fully formed that it’s easy to forget it was Peele’s first feature film. Daniel Kaluuya plays Chris, a black photographer visiting his white girlfriend’s family in upstate New York. But the director, drawing on tropes from Halloween and The Stepford Wives, has placed Chris in a nightmarish scenario in which he will be the next victim of a bizarre clan of predatory racists. The action unfolds with sharp wit, visual flair, moral urgency and allegory-rich attention to detail. TG

Eighth Grade (Bo Burnham, 2018)

The terror of being a teenage girl has never been so acutely realised on screen. In a powerfully naturalistic performance, Elsie Fisher plays Kayla, a 13-year-old who struggles with devastating social anxiety but attempts to project an image of herself as a cool, self-assured adolescent in awkward vlogs filmed in her bedroom. An excruciatingly embarrassing pool party sequence has all the tension of a horror film. AL

The Favourite (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2018)

Olivia Colman is triumphantly repulsive as Queen Anne in this gleefully irreverent history, which changed the tone of period dramas to come. Orchestrating a power struggle between Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, and servant Abigail (Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone – both tremendous), Colman’s manipulative, whiny and tyrannical monarch becomes pathetic and dishevelled. Foul language, explicit sex scenes, exaggerated makeup, fish-eye lenses and surreal dance sequences give the film a thrilling edge. AL

The Souvenir (Joanna Hogg, 2019)

The first part of a diptych (completed in 2021), this is a very personal contemplation of love, art, anguish and family by one of the UK’s best contemporary directors. Honor Swinton Byrne plays Julie, a naive film student who falls under the spell of rakish, eminently unsuitable boyfriend Anthony (Tom Burke). Swinton Byrne’s real-life parent Tilda Swinton plays Julie’s patrician mother, bringing a telling dimension of mirror play to an insightful retrospective musing on youth’s illusions. JR

Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, 2019)

First as farce, then as tragedy: South Korean director Bong’s remarkable register-shifting ability is on full display in his tale of a poor family who, one by one, infiltrate a wealthy household in Seoul. Who is feeding off whom? In this minimalist mansion with its chamber of secrets, the architecture of inequality is meticulously – comically, violently – mapped. TG

The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer, 2023)

It’s not just what we see on screen that gives Glazer’s Auschwitz-set domestic drama its sickening horror. Its oppressive power comes from the insidious, harrowing sound design and from Mica Levi’s feral howl of a score. This is profoundly uncomfortable film-making – one of the most memorable works of the century. WI

Nickel Boys (RaMell Ross, 2024)

Ross’s adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s novel is formally daring and thrillingly inventive in its approach – it is shot entirely from the first-person perspective – while also remaining faithful to the voice and spirit of the book. This is an impressionistic, immersive film that lets us see through the eyes of its central character: a studious, talented young black man in the segregated 1960s US who is sent to a hellish reform school. WI

Which of these films do you think is the best of the century so far? Vote on your personal top three here – and tell us what we missed

Photographs by Orion Pictures, Curzon Artificial Eye, BBC Films. Film4, IAC Films, New Regency Pictures, Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, Summit Entertainment, Miramax, Warner Brothers, Disney, USA Films