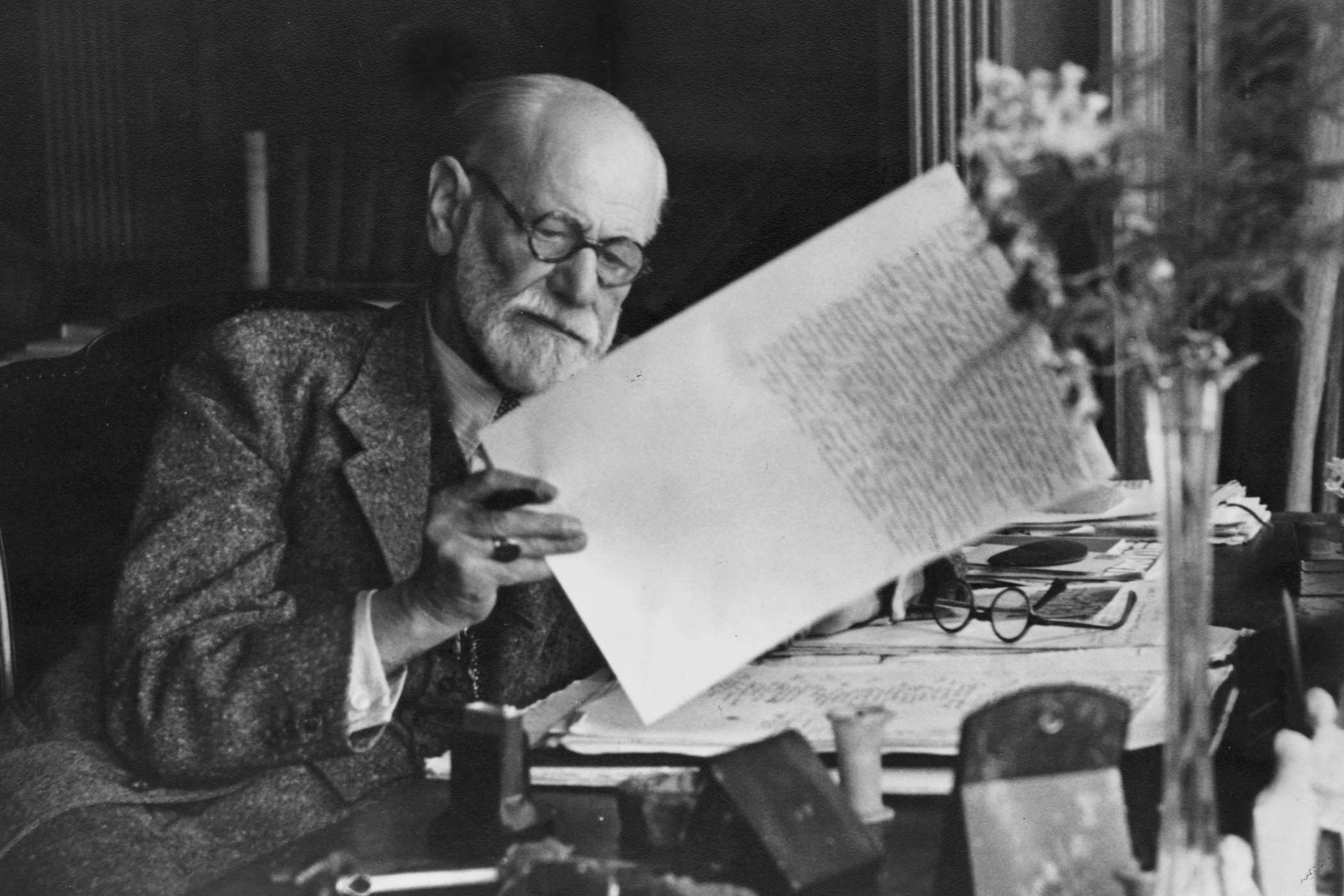

Photography by Hayley Benoit

At 34, I had sex with the last man I ever will. He was an old college friend who was visiting New York for the weekend. I had just gone through a horrific breakup and my life was a shambles. After 10 years clean and sober, I had become addicted to a person. Over the course of our two-year relationship, I crashed my car, damaged my health, lost friends and neglected everything and everyone I loved. In the aftermath, my best friend advised me to call this man who was in town for the weekend. “Call him and have him bed you,” she said. “It will make you feel better.”

This sounded unlikely, unlike me in every way. I had not slept with a man in years and had never enjoyed casual sex. “I don’t really date men any more,” I reminded my friend. “So what?” she said. “If I remember correctly, you’re capable of enjoying sex with men. You can stop if you don’t like it.”

Was that true? One of the things I remembered about sleeping with men was that it was hard to stop even if you didn’t like it. It felt easier to just keep going, because then you wouldn’t have to emotionally clean up afterwards. Masculinity was a glass vase perpetually on the edge of the table. My old college friend was a feminist, I reminded myself. I’d always thought of him as a nice guy, by which I meant that he wasn’t terrible.

Why not, I thought. I’ll try something different.

It was as easy as my friend had promised. I called the Last Man and he came over. The novelty of our sex was exciting, at first. But within a couple of minutes, I recognised the familiar tedium of being thrust upon. I knew what came next and it was not me.

When it came to love and sex, I seemed to be mired in a pattern

When it came to love and sex, I seemed to be mired in a pattern

The next morning, I pretended to leave for work so that he would leave with me. After we parted ways at the café on the corner, I walked home. As I closed the apartment door behind me, the pleasure of solitude was so great that I shut my eyes and leaned against the door with a sigh. I drank a glass of water and made the bed. My bedroom, having been intruded upon, felt sanctified in his absence.

After he went back to California, he started writing letters to me. He wrote me a letter every day for the next six months, an act that now sounds deranged, though at the time it charmed me. He was a very good writer of letters. That, combined with the 4,000 miles between us, was a powerful aphrodisiac.

While dating the Last Man, I began to fantasise about having a baby. I had always passively assumed I would eventually become a parent. I liked children and was good at cutting up fruit into bite-sized pieces. Suddenly, the obsession was so powerful I assumed there was a hormonal factor at work. The Last Man would be a good father, I thought.

The only problem was that whenever we spent more than one day together, I couldn’t wait to get away from him. His need for my attention emitted a very high-pitched whine, like a mosquito audible only to me. When I broke up with him, he tried to talk me out of it. “You’ll regret it,” he sputtered. I almost laughed in surprise, but restrained myself. “Maybe,” I said. “But I don’t think so.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

‘You’re making a colossal mistake!’ he shouted. Sometimes I still roll the phrase around in my mouth like a lozenge, and laugh

‘You’re making a colossal mistake!’ he shouted. Sometimes I still roll the phrase around in my mouth like a lozenge, and laugh

“You’re making a colossal mistake!” he shouted. Sometimes I still roll the phrase around in my mouth like a lozenge, and laugh: a colossal mistake.

After I broke up with him, I decided to take a break from sex and dating. I had been in nonstop relationships for almost two decades and had no idea how I had ended up in such a dire place after so many years of practice, and so many years of therapy. I was successful in many other areas of life, but when it came to love and sex, I seemed to be mired in a pattern.

First, I would fall madly in love with a new person and spend some months obsessed with them. Then things would settle down into domestic stability. Then I would begin making small concessions in order to please my partner. I would cut short a writing retreat to come home a few days sooner than planned. I would agree to eat at a restaurant I didn’t really enjoy. I would have sex when I wasn’t in the mood. These all felt like normal sacrifices, the sort I had always made. Didn’t everyone?

But over time, I felt hemmed in. I grew angry with my partners. Even if they had not asked me to make these accommodations, I began to feel coerced, as if merely imagining their disappointment obliged me to avoid it. Eventually, a persistent distance opened between us. Then I would get a crush on someone new. By the time I had dated the Last Man, the typical length of this pattern had shrunk from two or three years to six months. I was clearly bottoming out.

I decided to spend three months celibate. Not only would I abstain from sex, but also from dating, flirting and any other related activities. When I thought back to the amount of time I had spent pursuing my romantic relationships, it was chilling. I didn’t think of myself as a person who derived her self-esteem from her love life, but my actions told a different story. I was anxious to be truly alone for the first time, but nothing could have prepared me for the pleasures of solitude.

At first, I noticed the abundance of time. I caught up on all my deadlines and enjoyed long phone calls with friends. I taught classes at my university job with renewed enthusiasm. I went for long, languorous runs every day in the park, and read myself to sleep each night. On weekends, I didn’t look at my phone all day. Every other area of my life began to flourish.

There were physical changes as well. I had worn heels almost every day since my teens, but I traded them in for sneakers. I virtually stopped wearing makeup. I hadn’t realised how many of my daily choices had been contingent on the buried belief that I ought to appear attractive to others, to potential partners. Without the option of attracting anyone, I felt free.

At the end of the three months, I extended my celibacy for another three, and then another. During these months, I worked hard to scrutinise all of the hidden scripts that had been covertly guiding my behaviour. By the time I crossed the year mark, I wasn’t sure I would ever want to be in another romantic relationship.

Soon enough, I fell in love again. This time, with the Poet, an enthusiastic collaborator who shared my vision for a more conscious sort of partnership. I was approaching my late 30s by now and I soon brought up the question of parenthood. I still assumed I probably wanted children. My new girlfriend gently pointed out that nothing about my life suggested I would be well-suited to child-raising.

“What do you mean?” I asked, affronted. “You told me within days of our first date that you need to go away for months at a time to write,” she reminded me. “I mean, do you want to have a baby on your upcoming sabbatical?” I gasped. “I have a book to write on my sabbatical!”

Her knowing look said it all.

Still, I spent some time contemplating our conversation and saw that she was right. I didn’t actually feel excited about raising a human being; I just hadn’t wanted to miss out on anything. I marvelled at the sudden fever I’d felt while dating the Last Man. In hindsight, I can see that there was no “biological” urge, only a story I had been told about myself: that I would have children, that I would regret it if I didn’t. I had never really asked myself if I wanted to reproduce. I just acted as I had been instructed to believe I must. If I had not taken that celibate year, had not gotten to know myself as I did, and I shudder to think of all the ways my life would be different, like wearing the misfit clothes of a stranger.

Melissa Febos is the author of The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year Without Sex, published by Canongate at £16.99. Order your copy at The Observer Shop