Photographs by Antonio Olmos

Jonathan Crowther received the phone call that has defined his life from Mary Macnutt in 1971. “Derrick died last night,” she told him. “He wants you to take over.” Derrick Macnutt – better known to generations of crossword solvers as Ximenes – had set The Observer’s famous puzzle for 32 years, having inherited the role on the death of Edward Powys Matthews (Torquemada), who invented the concept of cryptic puzzles for this paper in 1926.

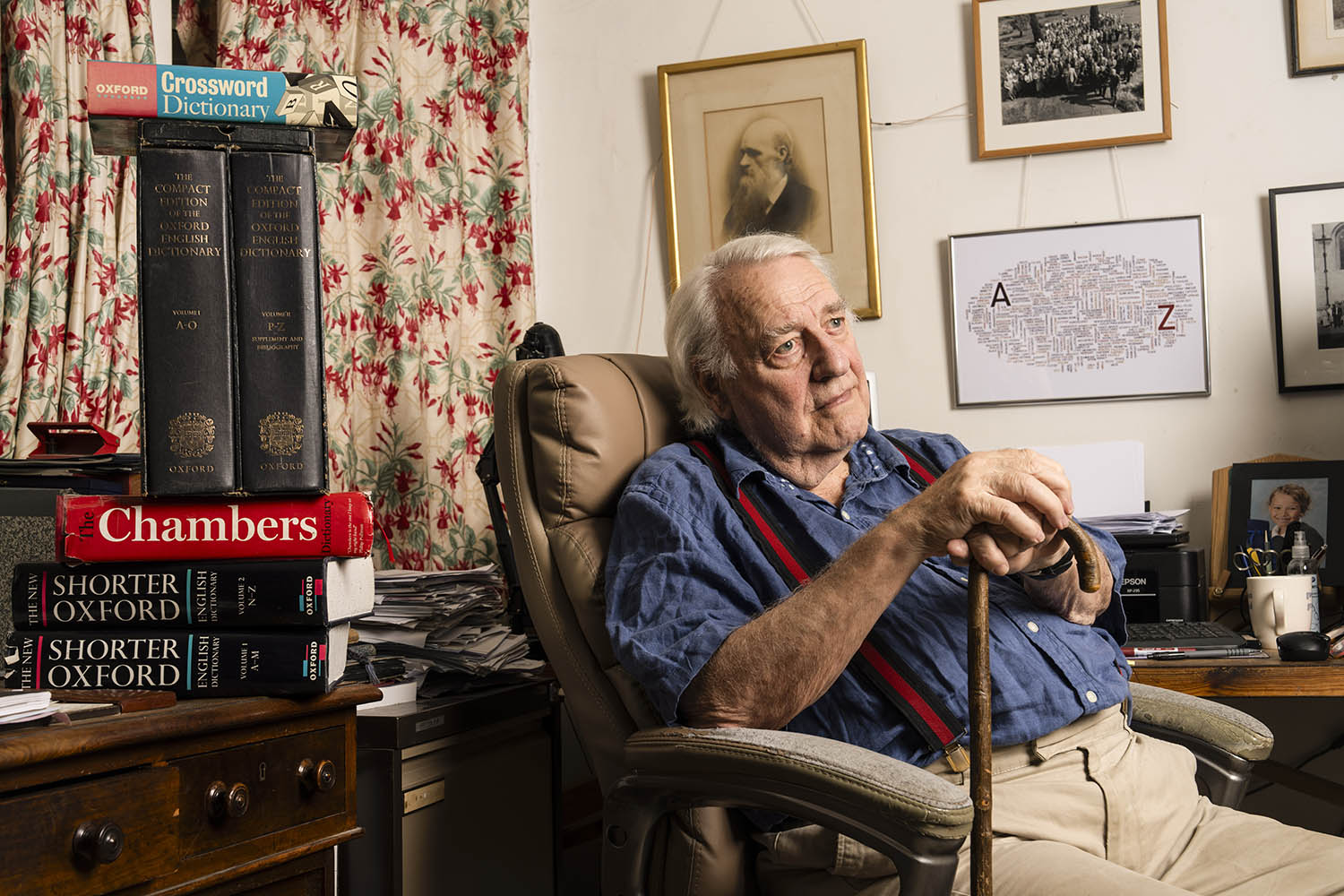

When he received that fateful call, Crowther was 28 and working as an editor of dictionaries at the Oxford University Press (OUP). Now 82, he says he was surprised to discover that he was Macnutt’s anointed heir, but he didn’t hesitate. To seal the deal, he sent an “in memoriam” puzzle in the shape of a large “X” in honour of his predecessor to The Observer’s crossword editor.

Crowther’s first puzzle for The Observer under the pseudonym Azed appeared on 5 March 1972. Azed has not missed a single week since – last week’s puzzle was No 2,768 – building a devoted community of followers used to having their Sundays punctuated by the demands of Crowther’s clues.

If this sounds like the beginnings of a valedictory tribute, those devotees can rest assured that it is not. Though from this week the weekly space always occupied by the Azed puzzle will be taken up by a new setter, Colin Thomas (Gemelo), Crowther will continue to set his special monthly prize puzzles, accompanied as ever by the invitation to devise a clue to match his own standards.

Sitting at the kitchen table of his rambling arts and crafts house in Summertown, Oxford, with his wife, Alison, he expressed to me some relief at the new arrangement. Though he senses no diminution in his powers, the pressure of doing a weekly grid was starting to feel a little too much like hard work. “It will be odd to start with,” he suggests, “but only having to do one a month instead of four or five, it will no doubt be a great relief.”

Like many crossword lovers, Crowther got the habit early, and it was invested with formative emotions: “My father was a GP, and I used to go out with him on his rounds, and he’d always bring the paper with him; we’d do the crossword in between appointments. I picked up the idea of cryptic clues quite quickly.”

Crowther studied Latin and Greek at Cambridge. Inevitably, given his precise and playful mind, he was approached while there by the cold war codebreakers of MI5, but he found the spooks who interviewed him for a job “a bit weird”.

He opted instead for a career in publishing. The OUP dispatched him to India, where he worked on dictionaries for language teachers; The Observer and its crossword, crisply delivered to the office a few days late, was a reminder of home.

He can’t quite remember when he first tried one of Ximenes’s puzzles – “At school, somebody said: ‘You ought to look at this chap in The Observer, he’s the best around’” – but Crowther was “hooked immediately”, he recalls. “Because it did seem to me that he had a set of principles in his clues, which he stuck to. And I thought: ‘Gosh, this is just what crosswords should be!’”

Until Ximenes came along, Crowther suggests, nobody bothered too much about rules in cryptic setting. “It was all too free and easy – and therefore a bit unfair [on the solver],” he says. “But Ximenes said every clue should have certain elements. One, it must always contain a definition of sorts. And every word in the clue must have a function, no odds and ends. And it should ideally be witty. I mean, not every clue can be a laugh-out-loud thing, but if you can, make them fun.”

John Finnemore, who sets the Listener puzzle in the Times (under the moniker Emu), has suggested: “The Observer’s three compilers form a sort of Socrates-Plato-Aristotle of cryptic crosswords. Torquemada essentially invents the form, Ximenes codifies it and Azed perfects it.”

In 2006, Crowther published the A-Z of Crosswords, an eccentric “lives of the artists” of the famous clue-setters, introduced with some principles of his own.

What makes a good clue? he asked – a question on which he has given a monthly commentary for more than half a century, in the conversational “slip” that accompanies his announcement of competition winners.

In his book, he sets out those criteria. Beside the usual trickery – word reversals, homophones and anagrams – there had to be certain maxims: “Say what you mean” was the first. A setter could use ambiguities, but once solved, the clue had to be seen to “lead unmistakably to the answer”. (So, for example, “The sort of leaves that hold up trains” might conjure a surface image of foliage on a railway line, “but eventually produces the only possible answer: pages”.)

The setter’s job is not to outwit the solver, he insisted, but to give them the satisfaction of completing the puzzle after a struggle. If Crowther has one abiding rule it is: “In any clue, always, always think of the solver.”

While he talks, Alison sits sipping tea and filling in bits of history. “Jonathan took over from two Spanish inquisitors, Torquemada and Ximenes,” she says. “He looked hard until he found a suitable third, Cardinal Deza; D, E, Z, A – so: Azed. I don’t think everybody knows that.”

There is something of a solvers’ satisfaction to their marriage. They first met when Alison was a chalet maid at the St Anton ski resort in Tyrol, Austria.

“It was really strange,” she says, “because I knew Derrick Macnutt, who was my friend’s father, and who terrified me as a small girl. Jonathan subsequently came to my flat back in London on the Old Brompton Road and while I made him lunch, he dashed off the Times crossword. ‘Oh, that’s impressive,’ I said. And he told me then about Azed. I said: ‘Oh, you took over from Derrick!’”

It felt like a completed puzzle?

“Yes,” she recalls, with a smile. “It was wonderful.”

I wonder about Crowther’s routine as a setter, when he was still working full time at OUP and helping to raise their two sons. “I’d get up early, about five, and do a couple of hours’ setting before I went to work,” he says, “and I’d come in at night and have something to eat and go off to my study and do more. It must have been very boring for the family.”

“It wasn’t,” Alison says.

“There are quite a few people who do it full time and set for several papers,” he says, “but I wouldn’t want to do that.”

Was there something special about The Observer?

“It was always an interesting paper,” he says. “I remember early on, about three of us were invited to a really very grand lunch in the then Observer offices on the Strand. Lord David Astor [owner and editor] presided, with one or two other bigwigs from paper at the time. I can’t remember how the subject came up, but we got talking about private personal finance. As we were going out of the door, Astor looked at me and said: ‘Tell me, what is a mortgage?’”

He and Alison have got to know many of the regular Azed solvers over the years. Every 250 puzzles, more than 100 of them gather for a lunch – the last, at Wolfson College, Oxford, in the spring, celebrated 2,750 puzzles. Eighty people came back to their house for tea.

One of the regular prize winners in the past was the late novelist Colin Dexter, creator of Inspector Morse. “We knew Colin for years before he started writing,” Crowther says. “In his first book, Last Bus to Woodstock, all the characters were named after crossword people. There was a very suspect character called Crowther in it. And, of course, Jeremy Morse [longtime chair of Lloyds Bank] was a really good friend and a regular competition winner.” (A battered trophy is still passed between monthly prize winners; Azed legend suggests that in the late 1970s, during an IRA bombing campaign, a first-time winner, R Adm Ridley, having received an unexpected parcel from Dublin, called in the bomb squad, who unwrapped his trophy.)

The kind of intelligence that can decipher Azed’s clues, still less conceive them, is not easily replicated. There is no danger that AI will produce a satisfying cryptic puzzle any time soon – there is too much human poetry in it for that.

Crowther could use ever more powerful software to help him fill in his grids, but he still sets them out week by week on squared paper in exercise books, with his trusted Chambers dictionary to hand. Traditions persist. Hundreds of people still send in stamped addressed envelopes (remember them?) to The Observer containing their completed grids. From this week, however, all new Azed puzzles will also be available online.

He likes the idea of working alongside the new weekly setter, Colin Thomas, in the paper. The first question he asked when they met was: “Are you a Ximenean?” – and he was gratified to hear a resounding yes.

“We like the fact he is very young,” Alison says – Thomas is 39 – “and can bring a new generation to it.” Crowther doesn’t often do other people’s crosswords these days – “I’m too critical,” he says, with a laugh – but he may well make an exception for his new colleague. “Even after all this time, I do think crosswords are a very good thing,” he says. “Long may they survive!”

Meet The Observer puzzles team

Colin Thomas

Gemelo

Colin Thomas is taking over as weekly prize cryptic crossword setter in The Observer from this week. Thomas, 39, who worked until recently as an actuary, grew up doing crosswords with his grandad. A couple of weeks ago, he finished second in the first ever World Cryptic Crossword Championships, a competition that involved solving three puzzles against the clock and then a sudden death round on stage answering random clues.

He describes himself as a principles-based setter. “I think it was [The Observer’s] Ximenes who said the worst thing about poor crosswords is picking up the paper the next day and seeing the answer and thinking, ‘Well, I thought the answer might be that but I still can’t work out why it would be.’”

Naturally, he has a slightly different set of reference points to older setters. “I think it’s good to have reference s to current things,” he says. “I mean, the Times only fairly recently stopped their policy that only dead people could be mentioned. Some setters still make reference to obscure Victorian actors. But everyone knows who Taylor Swift is – so why not use her in a clue?”

His pseudonym, Gemelo, (identical twin in Spanish), derives from the fact that “Thomas, my surname, means twin, and I’m a twin myself”. Previous Observer setters have taken names from the Spanish Inquisition, and Gemelo hints at that tradition, but Thomas didn’t want to be a torturer. “I’m my own setter,” he says. “I hope current readers love my puzzles, and that I can bring new solvers in.”

Caitlin O’Kane

Observer crossword editor

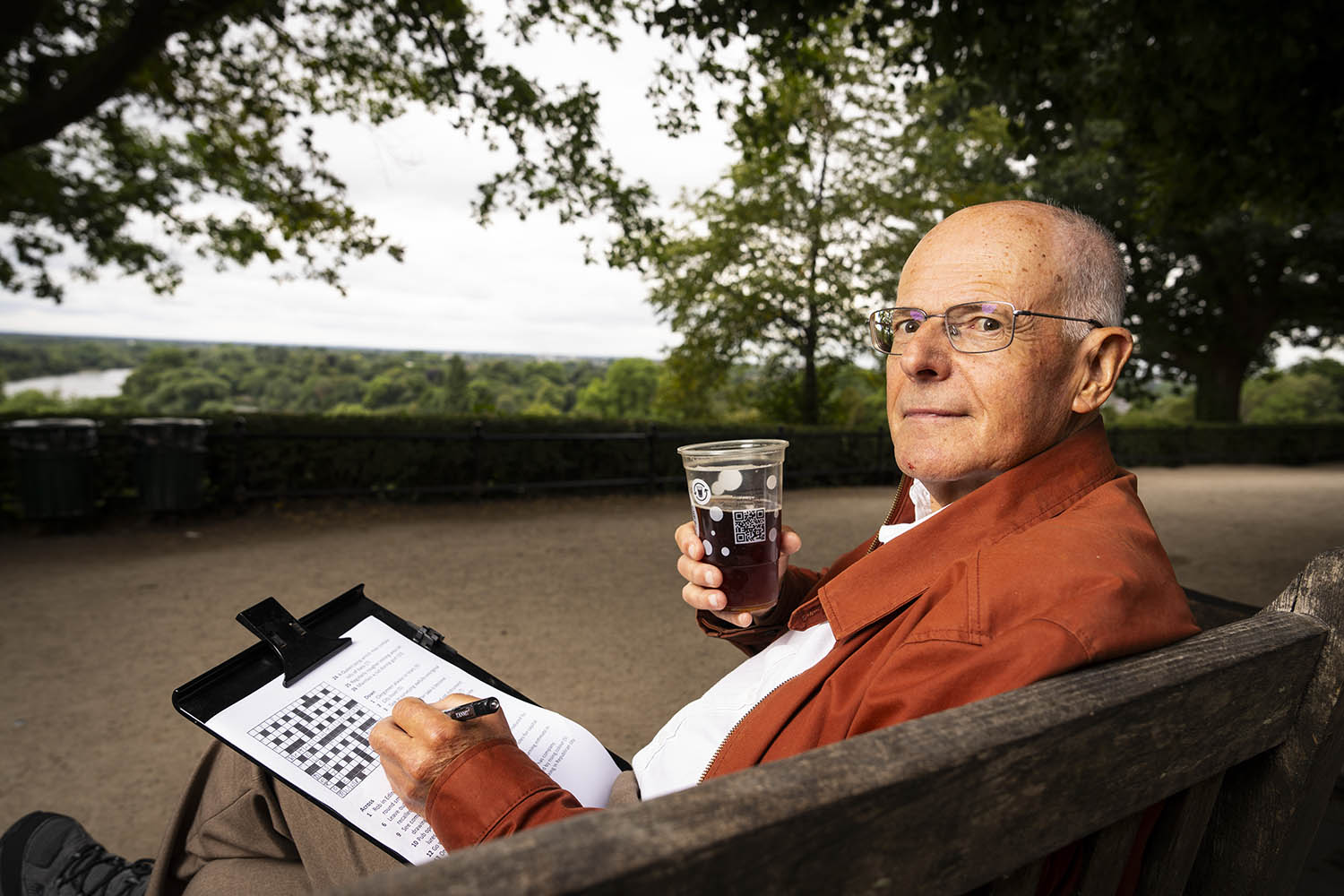

At the most recent Azed lunch, for the 2,750th puzzle, Caitlin O’Kane – who has cajoled, corralled and kept in line Observer puzzle setters for nearly a decade – proposed a toast to Jonathan Crowther. She paid tribute to an intense relationship “that has played out through production notes, phone calls, and carefully orchestrated back-and-forth emails – often involving the heroic diplomacy of John Grimshaw – to ensure grid, layout and clues all land each week just so.”

Like the good puzzler that she is, O’Kane recently found “a perfectly structured clue” to help answer the question of why she had landed this curiously involving job – one which saw her double-checking Azed pages while in labour with her daughter because nobody else had the required skills.

She grew up in Oxford, in Summertown, where her godfather, the former Observer journalist Mark Stanway, lived. Stanway and O’Kane’s father would sit in the Dewdrop pub doing crosswords when they were working together at the Oxford Mail. It was only after Stanway’s death, and after she had begun working with Crowther at The Observer, that she discovered that Azed would sometimes have a pint in that local too, often with Colin Dexter, creator of Inspector Morse. “I didn’t know any of that when I started this role,” O’Kane says, “but looking back it all fits into place, like one of Azed’s perfect grids.”

From September, O’Kane will write a weekly Observer newsletter “on puzzles, people and the stories behind them”; don’t miss it.

John Grimshaw

Azed editor

For the last six years John Grimshaw, who has written more than 5,000 crosswords for the Times as “Joker”, has been the first person to look over Jonathan Crowther’s Azed puzzles. “I started doing Jonathan’s crosswords in The Observer in 1972,” he says. “I loved the total freedom he had, because of the rules he worked by, to use any word in Chambers dictionary.”

Grimshaw is Azed’s checker. “Jonathan sends me the puzzles each week. First I solve them, then I give him a couple of comments back. Perhaps something I didn’t feel was quite clear, or a bit too difficult, or very occasionally, how about this?”

Grimshaw loves the fact that the crossword community offers a cross section of society. “You know people I’ve met through Azed lunches, like Sir Jeremy Morse, the head of Lloyds Bank, or postmen, teachers, people out of work, great authors.” He’s had lunch with Stephen Sondheim a couple of times: Sondheim was the first to introduce cryptic crosswords to a mainstream American audience when he set puzzles in New York magazine in the 1960s. The great lyricist told the story of how he and Leonard Bernstein would have certain favourite crosswords mailed to them each week from London so they could work on them in breaks from writing West Side Story.

Does Grimshaw think there is poetry in the best clues?

“Certainly you are always trying to write something that flows well,” he says, “that reads well. Jonathan’s Azed clues invariably create a striking image that the reader sees immediately – that is the first way to distract the solver …”

Alan Connor

Everyman

Alan Connor had been “probably the world’s only dedicated crossword correspondent” at the Guardian for about 10 years, when the Everyman job became available six years ago. Had he run out of cruciverbal breaking news?

“Well,” he says, “there were always stories of people losing their jobs because they were caught doing puzzles at work.”

Who is his “Everyman”?

“I always think the general knowledge that you would need to do my puzzle is what I might expect someone to have if they are a keen Observer reader. I see my job as making a puzzle that a lapsed or occasional solver can pick up and do.”

He confesses to being slightly daunted working alongside Jonathan Crowther’s Azed. “At the lunch for the 2,750th puzzle, I noted how it was disconcerting sharing a page with a man who for the last 50 years has written the definitive guide to what makes a good clue,” he says, with a laugh. He enjoys the liberties of his Observer colleague. “Jonathan is very happy to use the word ‘wanker’ as an answer,” he says, “on the basis that it is in the Chambers dictionary.”

Connor loves crosswords partly as a form of brief collective escapism into a world of words. “There’s a lovely quote from Joan Didion in her book about grief, The Year of Magical Thinking, which goes something like: ‘starting a day with the crossword is a way to read, or, more precisely, not read the newspaper’”.

Stuart Pawley

Godefridus – setter of Killer Sudoku, Obliks, Train Tracks, Marupeke

“I got involved setting for The Observer in 2005,” Stuart Pawley says from his home in York. “I did a Sudoku in the paper, which I thought was really rather Janet and John, and I wrote in saying you should do something more like a killer Sudoku. I sent a couple in that I’d created, and that was that.” At the time, Pawley was winding down from a stellar academic career in computational physics. Among many other things, he coded a crucial programme designed to test Peter Higgs’s theory of the fundamental particles of the universe. Creating puzzles was a diverting retirement plan.

He’d been too busy before then to indulge a latent passion from school. “I always remember one day a teacher said, ‘you’re going to have a go at last year’s IQ examination’. And it was a paper full of puzzles! Absolutely full of puzzles! I was delighted.”

These days he spends a lot of time looking for new kinds of puzzles for which he can develop robust computational models – he’s lately added Obliks and Train Tracks to The Observer’s pages, and more innovations will follow. “Having ideas for puzzles is rather like having ideas for doing research,” he says, of his former life. “At my department at Edinburgh, we always used to ask ourselves, where do these ideas come from? How do we generate them? The answer really is sort of luck, and whether you are made that way – and then recognising the good one when it arrives.”

A new Observer puzzles newsletter is coming soon, sharing puzzles, people and the stories behind them - trends, histories, insights and brain teasers all in one place. Sign up here to receive the first one.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy