4.30am 10 November

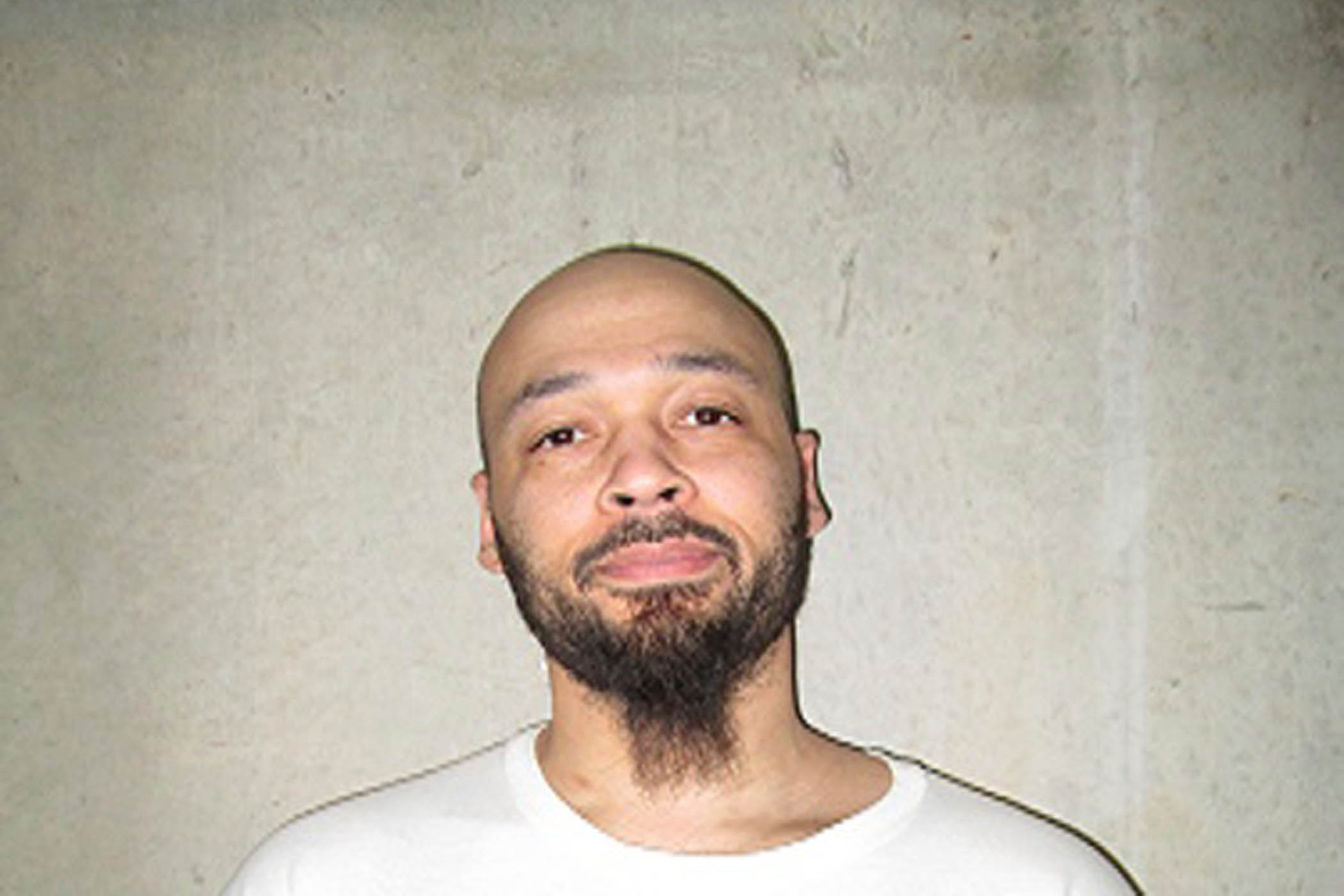

It was dark, and I was the only car on the wide open Oklahoma highway pre-dawn on 10 November. My stomach was a knot. At 10am I was to sit a few feet away from a man’s face, and watch him being put to death. A convicted murderer, Tremane Wood, was to be injected with lethal chemicals that have left others writhing and vomiting, a chemical protocol that one US Supreme Court Justice once said might be “the chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake”.

I was on my way to the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. I wondered: what would go through the mind of a man when dawn broke on the day he was to be killed?

Driving to an execution is not a normal drive, and my mind wandered. It wandered to the throngs who attended public hangings throughout the ages, to the blood I used to walk past after Friday beheadings in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia when I lived there in the 1980s. It wandered to my grandfather, who told me he had seen many men executed in the electric chair in Texas as a young crime reporter in the 1930s. And of course, my thoughts kept circling back to Tremane Wood and the day ahead.

I knew that he had spent the night in a transparent cell right next to the execution chamber, with its macabre gurney: two leg straps and two arm straps that would hold him prone, arms outstretched in a sort of crucifixion pose, ready to receive the IV through which the lethal chemicals would flow.

Three weeks ago, I had never heard of Wood. He had been on death row for 20 years. I was sitting at my desk in October when an email popped up from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections stating that I had been selected to join a lottery to witness his execution.

“Oklahoma Corrections. We Change Lives!” was the email sign-off.

I had put my name forward to witness an execution months before because my previous reporting had left me interested in the controversial death penalty drugs.

When the day came for the execution lottery I logged on to a Microsoft Teams link, struck by how grotesque this all was. On my screen appeared the neatly dressed Kay Thompson, from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections, in a brightly lit office. She held a small box containing the names of the various news agencies. My heart started beating rapidly. I no longer wanted to be selected. My company’s name, Hayloft Productions, was pulled.

“Will you be attending?” Thompson asked.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

I was leaning on my kitchen counter by now, camera off, cursing under my breath. “Yes”, I said.

The viewing area in the execution chamber at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester

6am, four hours until the execution

I was more than halfway between Oklahoma City and the prison in McAlester. Wood would be awake by now, with four hours left to live. The night sky was clear and vast, blanketed by bright penetrating stars, a sky that he had not seen in a long time.

Before being transferred to cell next to the execution chamber, Wood had spent months in the prison’s notorious H Unit, reserved for miscreants and some death row prisoners. H Unit is partly underground. Prisoners have described it as a tomb, a place where you feel like you have been buried alive.

Wood’s concrete cell this summer, said his mother Linda, was filthy and tiny. “The conditions were worse than you would put a rabid dog in,” she said. “There was mould, and there were swastikas carved in the wall. When they wouldn’t even turn the lights on he’d just sit there in the darkness because he didn’t have a window.”

In “the hole”, as prisoners call this disciplinary section of H Unit where Tremane spent at least 30 days this summer, inmates say they are not allowed any possessions and are locked up alone in their cells for between 22 to 24 hours a day. During a spell in “the hole” this summer, Wood indicated to a social worker that he was suicidal, saying he had tried to make a noose and had stashed pills.

It was strange, I thought, as I drove, that for his last week on Earth, they would take a death row prisoner from the darkness of H Unit to a cell lit 24 hours a day with a transparent wall.

In Oklahoma they call this “death watch” – a period when prisoners are monitored around the clock, presumably to ensure they don’t take their own life. Wood, according to his lawyers, said he felt like he was a lab experiment.

What had frayed Wood’s nerves the most in the last week, though, was that written contact with his family and friends was cut off. Contact with family, he said, had been keeping him from “going over the edge”.

Yesterday his family had been allowed to visit him to say goodbye. They said he smiled a lot because he was allowed to hug them, for the first time in months.

“I never thought that somebody could be sent to death row who didn’t kill anybody,” said his mother.

Wood was to be executed for the 2002 murder of 19-year-old Ronnie Wipf, a murder to which Wood’s brother Zjaiton, or “Jake”, confessed. Jake got life in prison without parole. Tremane got death.

How did it come to this?

Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, where Tremane Wood (main image) was on death row

Tremane Wood’s childhood

A few days before Wood’s scheduled execution, I visited the rundown town of Guthrie, where he and Jake grew up. There I met their older brother, Andre, a tall, warm African American man with a calm voice.

Standing on the pavement, he pointed to the small house across the street. “That’s where a lot of it happened”, he said.

Their father, Raymond Gross, a local police officer, had violently abused their mother Linda for years. The boys witnessed much of it.

“My dad put my mum on a bed, tied her to the bed naked, put alcohol on her, and lit a zippo and told me to tell my mum goodbye, and then shut the door. He was going to set her on fire,” said Andre.

Linda was tied with electrical cables, slammed into glass doors, handcuffed to a swing set and left overnight, and beaten relentlessly.

On one occasion, Gross handcuffed her to a car. “I was on the outside of the car,” Linda told me, “and he drove off and dragged me down the highway.”

When Tremane was about five years old, Linda fled to California without her sons, said Andre. “Tremane kept asking my dad where my mama was. He’s like, dad, where’s mama? Where’s mama? And my dad told us she died. She’s dead. Tremane was crying. That’s the kind of heavy shit we had to deal with.”

Down the road Andre pointed to another house where Tremane had been sexually abused as a boy.

Linda was white, her husband was black. Growing up in a mixed-race household in a predominantly white town in Oklahoma, Andre said, meant they faced constant exclusion and racism.

Jake, described by friends as large and aggressive, became Tremane’s protector. “Tremane idolised Jake,” said Andre. Jake brought Tremane into a gang at a young age. In their childhood they were intermittently forced apart in juvenile detention centres and foster homes.

“When Jake was out of the house, Tremane excelled,” said Linda. “But as soon as Jake was back it started all over again.”

The murder

As New Year’s Eve 2001 approached, Tremane had been working in a pizza restaurant, and had two children of his own. Jake had recently been released from prison.

That night, the two met at the Bricktown Brewery in downtown Oklahoma City where they joined two female friends, Lanita Bateman and Brandy Warden. Two young men from Montana, Ronnie Wipf and Arnold Kleinsasser, were also in the bar. Between the brothers and the women that night, a plot was hatched to rob them.

The women went with the Montana men to a motel room, promising sex for money. Jake and Tremane burst in wearing ski masks. The smaller man was holding a knife, the larger man a gun, according to court testimony from Kleinsasser.

There was a struggle as Jake and Tremane tried to rob the men. Wipf died after the knife was plunged five inches deep into his chest. Both brothers and the two women were accused of being responsible for Wipf’s death.

After the murder it was found Jake had a cut on his hand. Tremane’s defence lawyers argued that Jake had sustained it from the gun’s slide, causing him to toss the gun, grab the knife instead and stab Wipf himself. The prosecution argued that it was Tremane who wielded the knife, calling it “far-fetched” to suggest the knife changed hands mid-struggle.

Bricktown Brewery in Oklahoma City, where Tremane and Jake Wood, along with two women, hatched a plan to rob Ronnie Wipf and his friend

The trial

Under Oklahoma’s felony murder rule you can be convicted of murder for playing an active role in a felony such as armed robbery that leads to a murder, whether or not you actually killed someone. So in Tremane’s trial the issue of who actually stabbed Wipf was strangely irrelevant.

Tremane’s trial was plagued by problems.

“There wasn’t a case,” said Andre his brother simply.

Tremane was represented by a lawyer, John Albert, who was abusing alcohol and cocaine at the time, according to court affidavits. Albert logged a total of two hours of work on Tremane’s case outside of court time, according to the Legal Defense Fund.

Jake took the stand during Tremane’s trial and confessed he had stabbed Wipf, but the jury did not believe him. Albert had left critical corroborating information out of his case.

Bateman spoke about Jake’s admission immediately after the crime, and is quoted as saying: “[Jake’s] mum asked what he had done now … He took her to her room and told her that he thought he killed a guy.”

Albert failed to hear evidence from Tremane’s cousin Roshonda Jackson. The day after the murder Roshonda was in the car with Tremane. “He was crying really bad and shaking,” she said. “He just kept screaming nobody was supposed to die, nobody was supposed to die.”

Tremane was found guilty of first-degree felony murder and sentenced to death.

Jake had a team of well-resourced lawyers and was also convicted of first-degree felony murder, but sentenced to life in prison without parole.

After Tremane was sentenced to death, Albert scrawled a note to his client on a business card: “Sorry, you caught me at a bad time.”

The gurney to which prisoners are strapped in the execution chamber at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary

7am, three hours until the execution

Just before 7am my car entered the town of McAlester. The Oklahoma State Penitentiary rose into sight just as the dawn broke, a white fortress with battlements, perimeter floodlights blazing.

Tremane now had just three hours to live, unless the US Supreme Court or Oklahoma’s governor, Kevin Stitt, granted last-minute clemency – a rare occurrence in this rightwing state.

The countdown was on. At 8.30am in the press room, the woman who ran the lottery, Kay Thompson, was smiling politely as she welcomed in a handful of local journalists who seemed used to the routine.

9am

Five of us would be taken by bus to the execution chamber viewing room. We were not to talk. At 10am the curtain would be raised. Wood would be strapped to the gurney, an IV inserted, the chemicals – a three-drug “protocol” of midazolam, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride – administered. His body would be put in a body bag and taken out.

9.20am

The US Supreme Court had denied clemency. I felt nauseous, it crossed my mind that I might vomit during the procedure. I tried to block any emotion.

9.30am

Wood, I later found out, was taken to a room where he would wait to be brought in to the death chamber. “Tremane said that in that last half hour he had mentally worked himself up to prepare to face the end, to go in there and be strapped to the table and be executed,” said his lawyer Amanda Bass Castro-Alves.

The bus had not come to take us to the chamber. The journalist next to me muttered: “We’re usually in there by now.”

Back in Oklahoma City Linda, who could not face attending, was sitting on her bed distraught. The waiting, she had told me the night before, was “agonising, agonising.” Tears rolled down her cheeks, and she set her jaw defiantly, a woman who knew too well how to endure pain, but perhaps not this time.

9.40am

I wondered if Wood could see a clock. In his clemency hearing a week ago I had heard him say: “I’m not a monster. I’m not a killer.” He had begged for recognition of his worth as a human. “I ask you board members to see something in my life worth value.”

9.50am

I remembered my conversation with the mother of the murder victim. Barbara Wipf, from a deeply religious Hutterite community in Montana, had talked in a thin, faltering voice on the phone. She did not want Wood’s execution to go ahead.

Why? “Because we believe God judges, on judgment day.” The Wipf family had relayed their view to the governor in recent days.

The last minutes ticked by. The clock reached 9.59am. One minute to go. Thompson rushed out of the room on an urgent call and came back in.

“Clemency,” she blurted out. “Clemency.”

Wood was standing up when he was told. “He said he just collapsed on to the floor, literally just collapsed,” said his lawyer.

Later that night Wood was found unresponsive in his cell. Once again he had collapsed due to stress and dehydration. He later recovered.

Outside the prison his son Brendan, who had driven 18 hours from North Carolina to watch his father be killed, said: “I believe that a person wholeheartedly thinking they are about to take their last breath, and it’s coming down to seconds, minutes before the decision is made … I find that to be mental torture.”

“It’s close to a mock execution,” said Castro-Alves. “You walk to the very brink and then you’re pulled back.”

Oklahoma is Trump Country

Donald Trump has ushered in a flurry of executions in America. More than 40 have taken place since he lifted Joe Biden’s execution moratorium in January, some by firing squad. Oklahoma voted overwhelmingly for Trump in the 2024 presidential elections.

In Sid’s Diner in El Reno, Oklahoma, Adam Hall, who was flipping burgers on the stove, said that his views on the death penalty were simple. “A five cent bullet would be easier.” He argued that murderers ought to know what it feels like to be killed.

A former naval commander, Ray Alexander, who lives nearby went further. “I’d support public hangings,” he said, adding that he would support public beheadings too if a state voted for them.

Governor Stitt, in his statement granting clemency to Wood, said he would pray for the Wipf family, calling them “models of Christian forgiveness and love”. The Wipfs’ opposition to Wood’s execution seems to have played a large role in the governor’s decision.

More than 2,000 Americans face execution by chemical injections, or in some cases nitrogen gas or the firing squad. Wood will now live and serve out his new sentence of life without parole.

Wood’s lawyers say he is still in disbelief that mercy was granted. He wants a new trial, but that’s another battle.

Due to earlier prison rule violations, Wood is back in H Unit, in a solitary cell, incommunicado except through his lawyers. He has said its very noisy and prisoners often light fires. In disciplinary units here banging on cell doors, yelling and screaming are common.

Andre says he will cope. “My brother is strong as hell. To stare death in the face at the last minute and to be able to turn around and walk away and say, it ain’t ready. I’m not ready, you have to be one of the strongest people in the world.”

Photographs by Getty Images/AP