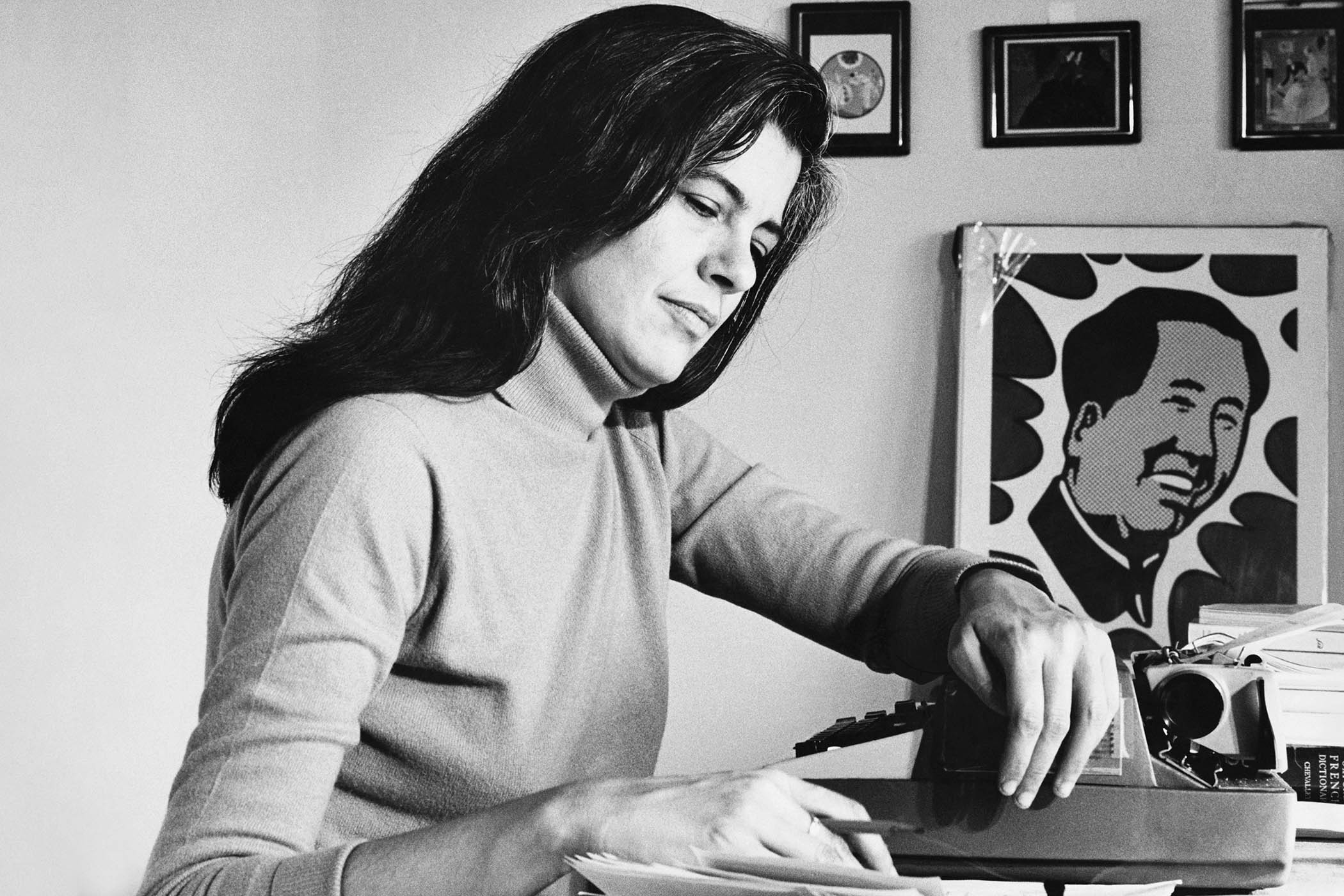

Joyce Carol Oates, 87, is the author of more than 60 novels, including them (1969), set in 1930s to 1960s Detroit; Blonde (2000), her fictional account of the life of Marilyn Monroe; and Butcher (2024), about a terrifying doctor at a 19th-century women’s asylum. A five-time Pulitzer finalist, her many prizes include America’s National Book award and the Bram Stoker award for lifetime achievement in horror fiction. Oates spoke from her home in Princeton, New Jersey, about her new novel, Fox, which is named after its villain: a teacher at a prestigious boarding school.

Tell us how Fox began.

I wanted to experiment with the classic whodunnit, a form I hadn’t done before. Walking in a bird sanctuary near where I live, I was daydreaming about a charismatic middle-school teacher preying on his vulnerable girl students. I was interested in his psychology.

How did you imagine your way into it?

I once wrote a novel called Zombie [1995] from the point of view of a serial killer [based on Jeffrey Dahmer] with intense contempt for women’s bodies. Writing from the point of view of a real misogynist was an interesting experiment, but Fox is the kind of person who, if you met him, you’d like him. He’d find something out about you – “Do you like soccer?” – and play to it and flatter you. He looks like Hugh Grant once did; he’s attractive; he’s got nice clothes.

Were you drawing on a real case?

It’s not identical, but I had in mind a case in which an exploited girl may have [died by] suicide. When girls – and boys, I suppose – fall in thrall to a predator, they often harm themselves but rarely accuse the predator. I was thinking of the charismatic political leaders we have – that dark charisma where it’s pretty evident they’re corrupt, even criminal, yet people love them.

The detective in the novel thinks: what would Fox have to do to finally be accused? The answer is: there’s almost nothing he could do; when you have a predator in the community, he’s often protected, even after his death.

Related articles:

Does publishing a new novel give you the same feeling it did when you started out in the 1960s?

For people who write a lot, there’s a very big difference between what the publisher thinks is a major novel and what they acknowledge is probably not. I’ve had novels that the publisher thought would be major. Bellefleur [1980] would probably be the first; that was big and well reviewed, a bestseller. Then there was We Were the Mulvaneys [1996], an Oprah’s Book Club selection that sold more than a million copies. But most books come out quietly. If you keep writing, you have these ups and downs. The things I’m doing are kind of experimental but I’m the only one who knows it. In some ways, I’m writing into a vacuum.

You don’t seem daunted by that...

Well, I like to experiment. My novel Breathe [2021] was a lot about my experience as my second husband, Charlie, was dying, and the dreams you have when you’re accompanying a person to death. It’s the kind of experience I think some widows and widowers have, where a rational part of your mind knows certain things, but the dreaming side may believe in hauntings and all sorts of odd things when you hold in your arms someone who’s dying.

I wanted to write about that but I also had these vignette chapters about a person in a fever state, infected by brain-eating bacteria. You think you’re reading about the dying husband, but if you read the novel twice, it’s not clear if it’s actually the wife; the whole novel might be her hallucination. I wanted that doubleness.

I did it with Babysitter [2022] too, but apart from maybe a writer friend of mine, probably almost nobody reads these novels with the care they would need to understand them.

Did you expect to draw so much attention with your 2021 tweet deprecating the trend for “wan little husks of ‘autofiction’”?

I don’t have strong opinions on autofiction; you could say almost every poet was writing autofiction. Twitter [now X] is very trivial and extremely ephemeral.

The context was that I was reading novels of profound social significance as a juror for the Anisfield-Wolf Book awards [for books that contribute to the understanding of racism]. We gave our [2022] award to Percival Everett’s The Trees and I was thinking of the magnitude of some of the black writers we were reading. To set them beside autofiction ... I don’t want to condemn it by calling it “white” but there just seemed a painful contrast between the work Everett is doing and typical autofiction, which seems very narrow, takes almost no chances and says very little about the racial conflict that is so dramatic and terrifying in the US.

How do you view the atmosphere there since you wrote A Book of American Martyrs [2017], your novel about abortion?

When I wrote that, the division [in society] wasn’t as strong as it is now. You had a liberal secular administration and a minority of very angry people assassinating abortion providers. That was a real thing in America some decades ago. Now the right wing have won the electorate, they don’t have to assassinate people any more.

As a reader, is there a particular novel you return to?

On a desert island, I’d take Ulysses. I like DH Lawrence very much, but he doesn’t have the variety or audacity James Joyce has. Ulysses has everything except violence. Joyce didn’t believe in writing about it – I’m not anything like Joyce in that regard – and there’s nothing in it about really terrible suffering, like the famine. Even without those things, it’s still the greatest novel in English.

Fox is published by 4th Estate (£18.99)

Photograph by Maria Spann for The Observer

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy