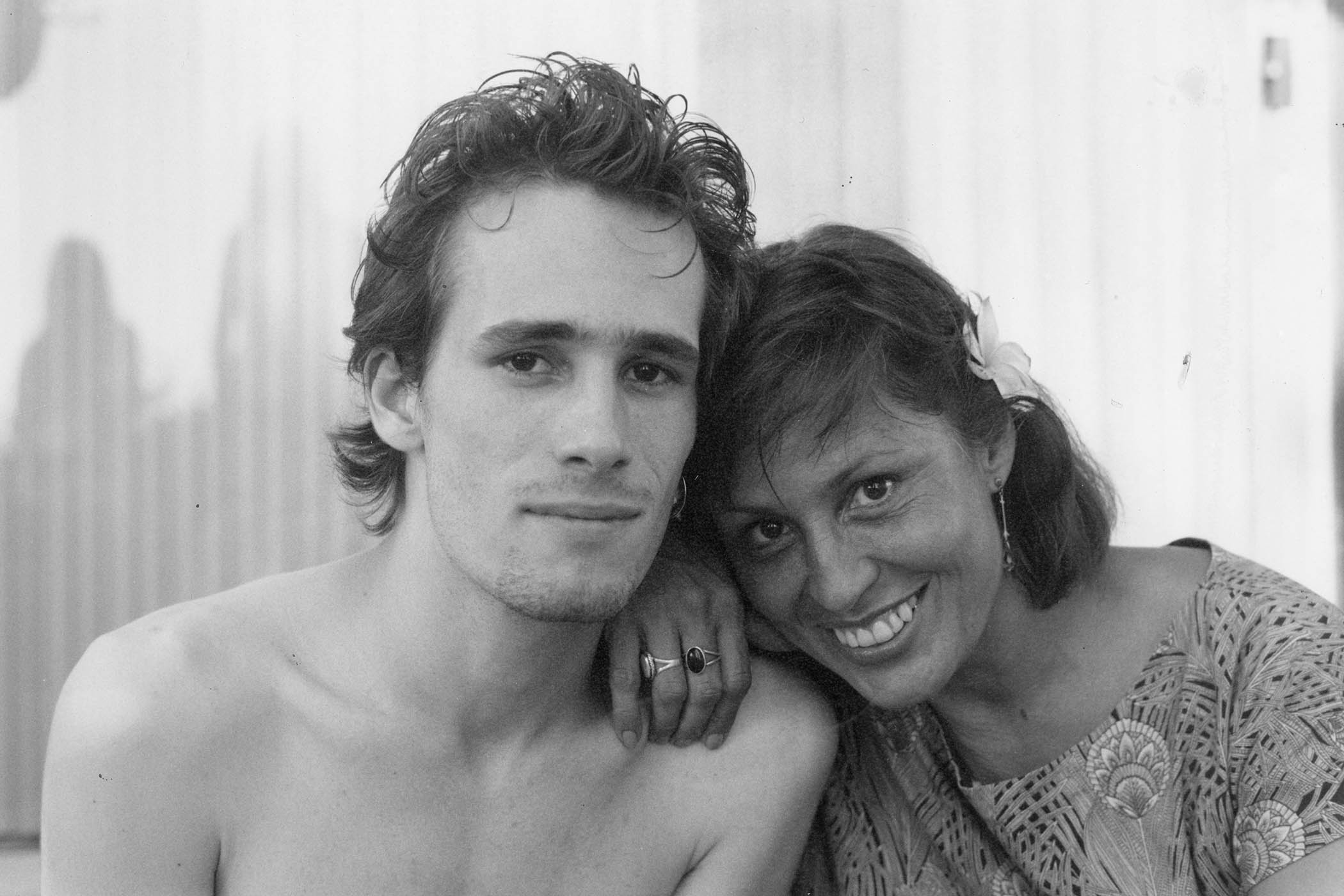

Portrait by Amy Harrity

Mary Guibert thinks her son Jeff Buckley revealed his musical talents early. Very early. It was 1967, Guibert was 19 and, abandoned pre-birth by her baby’s father, the musician Tim Buckley, she had moved in with her parents and two siblings in Orange County, California.

“I’m back in my old bedroom with the crib in the corner, escaping what was no kind of life, right?” the Panama-born Guibert, 78 this month, says over video-call from her home near San Francisco. “And I can hear Jeff singing to the radio, just vocalising. I’m thinking: ‘Oh no, you’re delusional, Mary. It’s not happening.’ But I open the bedroom door and there’s this little baby with his mouth open, going…” Guibert ululates melodically, delighted at the memory. “I’m like: ‘What the...?’ He’s six months old!”

Even as a baby, Buckley was immersed in music. Guibert’s brother sang in a band that played the beach towns south of Los Angeles. “So he woke up in the morning singing.” The radio was on constantly. When Guibert was pregnant with her son, she would play the piano, “just to get through my day. My belly would be pressed up against the soundboard of the piano,” she recalls. “He was hearing me sing long before he even popped out. His little brain and his nervous system were imprinted with music. I don’t have to be a scientist to see the connections there.”

Mary Guibert wearing a necklace and earrings with ladybirds, which remind her of her son, Jeff Buckley

In the truck on the school run, Top 40 radio was their soundtrack – or Carole King, or Barbra Streisand (Buckley was a “massive fan”). “Whenever we had music on, we were singing along. Then for him to be able to carry a tune while I harmonised? That was six, seven years old,” Guibert says, smiling.

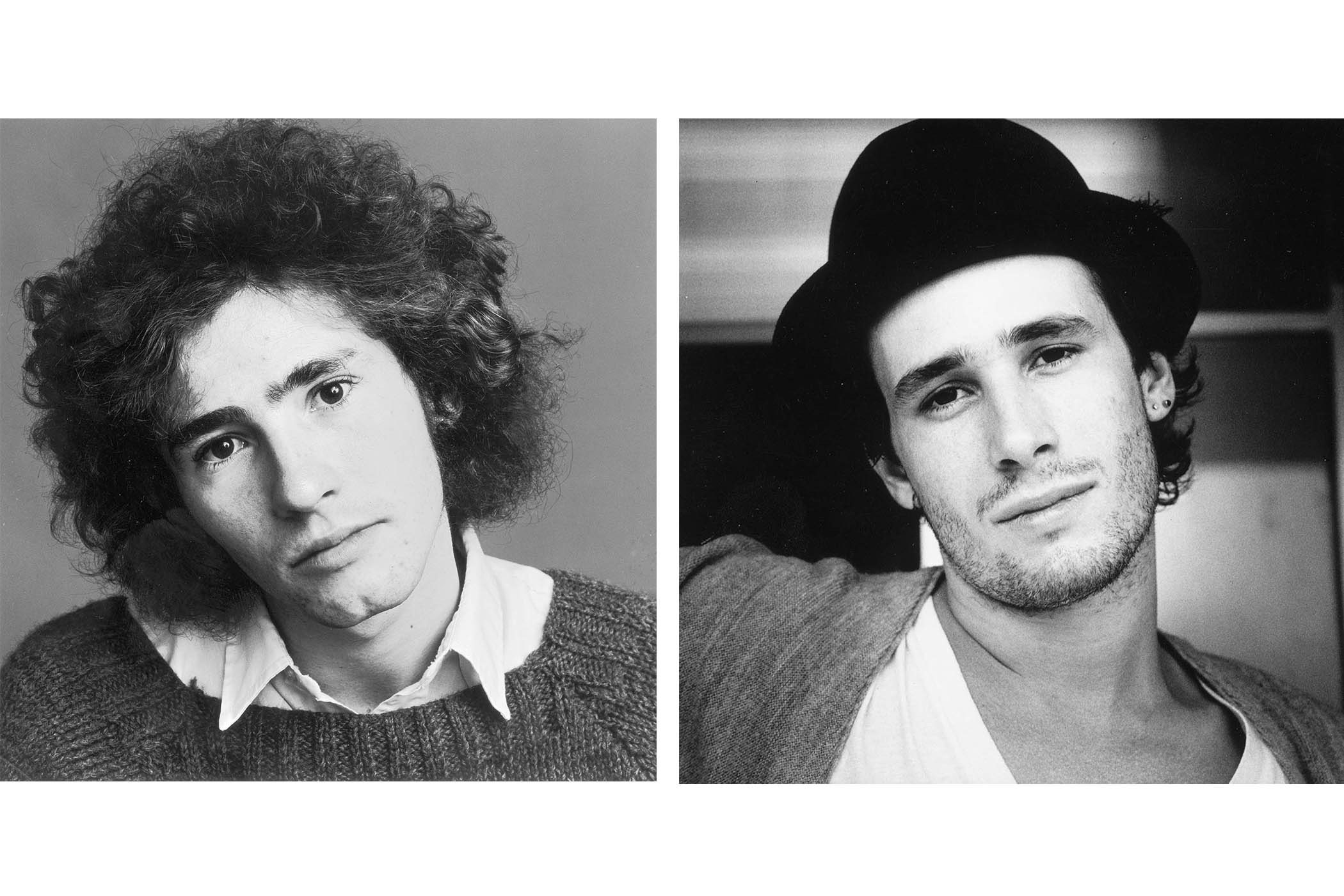

I suggest Buckley possessed two sets of musical genes, maternal and paternal. “For music, I firmly believe it’s more nurture than nature,” she replies quietly, distancing her son’s talents from those of his father, a revered figure in the 1960s and 1970s West Coast music scene. “People would say to Jeff: ‘Well, where do you get your voice? Did you inherit it from your dad?’ And he would say: ‘The only thing my father ever gave me was a fleeting glimpse. Next question.’”

That’s how Jeff Buckley’s life began; it ended on 29 May 1997. He had spent much of the previous three years touring the world, chasing the incremental international success of his 1994 debut Grace, a sublime set of soulfully-sung rock songs including a haunting cover of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah. His only studio album, it made him a beloved, cult artist. But Buckley did not enjoy the fame that record brought him. A major label artist with stoutly independent values, he struggled with the experience, as is made abundantly clear in It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley, a revelatory and poignant new documentary directed by Amy J Berg. But by late spring in 1997, Buckley was in Memphis and seemingly in a good place, finally ready to start in earnest on his second album.

That May night, singing Whole Lotta Love by Led Zeppelin, Buckley waded, fully clothed, into the Wolf River. Currents and the wake from a boat pulled him under. His body was found six days later.

Related articles:

Buckley wasn’t drunk, as testified by both the member of his road crew who was with him and by the coroner’s report. He wasn’t suicidally depressed, as his journals, which Guibert reluctantly pored through in search of answers, corroborate. His death was ruled an accidental drowning.

The subsequent myth-making, though, was inevitable. Buckley, 30, was too old to be in the “27 club” – or “that stupid club” as Kurt Cobain’s grieving mother termed it – but he was still bracketed with those artists who’d died at that age (Cobain, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and, later, Amy Winehouse). Buckley’s father had died at 28 from a heroin overdose. All this contributed to an image of Buckley as another tragic, reckless, rock’n’roll victim.

Guibert objects to this picture. As a child, Jeff had seen first-hand what that lifestyle did to his dad. I last met Guibert in 2007, at her then-home in Los Angeles, ahead of the release of So Real: Songs from Jeff Buckley, a compilation record marking the 10th anniversary of his death. She described to me eight-year-old Jeff’s one and only visit with his absent father, a week over Easter in 1975, shortly after mother and son had seen him in concert. “What he remembered of that visit is very, very meagre,” Guibert told me. “Because Tim was doing cocaine, which meant he was up all night and sleeping all day. All Jeff could remember was watching cartoons with [Tim’s stepson] Taylor and having to be very, very quiet ’cause daddy was sleeping in the next room.” Hence, she added, Jeff’s later quote about the meagreness of his father’s legacy to him, that “fleeting glimpse”. Tim died a little over two months later.

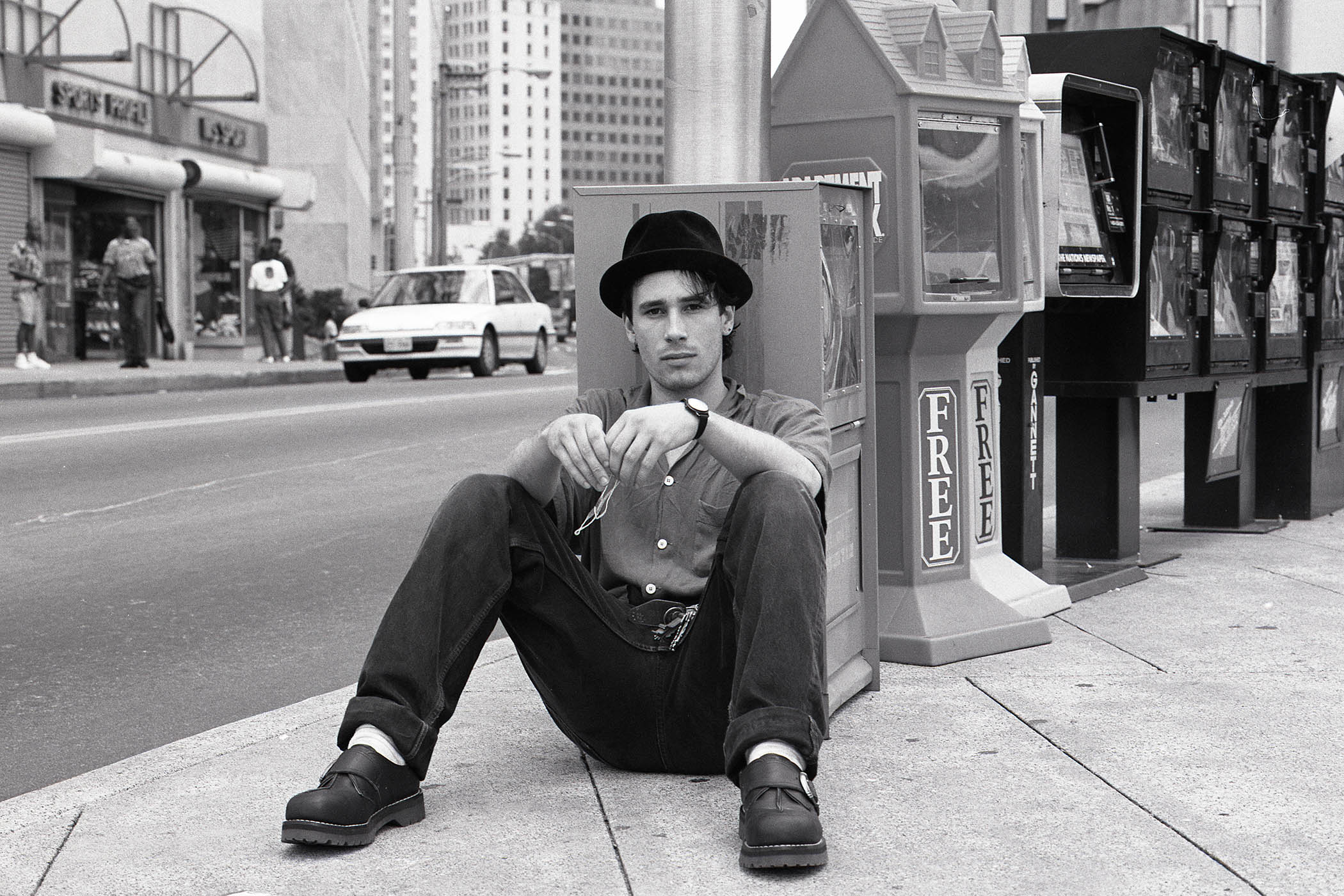

Buckley in Atlanta in 1994, the year his debut album Grace was released

Speaking now, Guibert says her son was “bound and determined not to do what his dad had done”. She admits he may have dabbled in drug use. “There are people who say, ‘Oh, I saw him snort this or snort that.’ I don’t doubt that,” she says. “But there were people really close to him, like [tour manager] Gene Bowen, who was in recovery, and very adamant about sobriety. If he had any idea that Jeff was using in a way that wasn’t just experimental, or that he was using in a regular way, we would all have known about it.”

This is partly why Guibert agreed, after many years’ back and forth, to the making of a documentary about her son’s life. At a London screening in December, Berg said in a Q&A that she tried to secure the rights to Buckley’s story “for about 10 years,” with Guibert eventually agreeing to collaborate with her in 2019.

“I think she trusted me at that point, finally,” said Berg, whose CV includes biographical projects about Joplin (2015’s Janis: Little Girl Blue) and the actress Evan Rachel Wood (2022’s Phoenix Rising). “And she was getting older. I think she wanted to be around to see this happen.”

As executor of her son’s estate, Guibert acknowledges that she is fierce in controlling how his life and work is honoured and, yes, monetised. In 1998 she oversaw the release of a compilation of “sketches” for Buckley’s unfinished second album My Sweetheart the Drunk – but only after sending his label Sony a cease and desist letter and forbidding them from polishing his demos. Guardian of the Buckley legacy, though, is not a job she wanted. “If Jeff were alive, I’d be living in some little cottage somewhere in the hills, enjoying my retirement,” she says, fighting tears. “He would have said: ‘Mom, if I die tomorrow, bury it. Don’t do a thing. You don’t owe the world anything. I was alive. I made my music. I sang while I was alive, and I’m gone. Do not feel obligated to deal with Sony, or my fans, or Tim Buckley’s fans.’”

The singer, right, and his estranged father, Tim Buckley

But the manner of his death left her with no option but to protect his memory, and she holds it close. The ladybird earrings she’s wearing when we talk are, to her, a symbol of her son’s spirit: when his body was identified, a ladybird flew out of his belly button. Her initial hope for a film was a feature biopic due to be directed by Jake Scott, the son of Ridley Scott. He “had a vision for it that set my heart on fire,” Guibert says. “Because it wasn’t going to be a standard linear biopic. He had these wonderful dreams about animating Jeff’s aesthetic.” But when budget became an issue, Scott left the project. Guibert eventually considered a documentary.

She certainly had the raw material. In 2007, we sat in her garage. It was stuffed with mementoes of her son and his music: gold sales discs from around the world, battered guitars, a sack of fan mail heavy with grief-stricken “lamentations”, 80-odd CDs of concert recordings, an entire wall of filing cabinets crammed with paperwork.

That archive was in the process of being preserved and protected by one of her son’s many fans, Brad Pitt. The actor, when he was finishing filming on 2001’s The Mexican, had taken it upon himself, with Guibert’s blessing, to look after the artefacts related to her son’s life and work. Catalogued and digitised, the Jeff Buckley archive now resides in a climate-controlled vault in Seattle. That includes the devastatingly intimate answering-machine messages from Buckley to his mother that we hear in the documentary. “Those were transferred by Brad’s sound man from The Mexican,” remembers Guibert. “He sat in my living room for a month.”

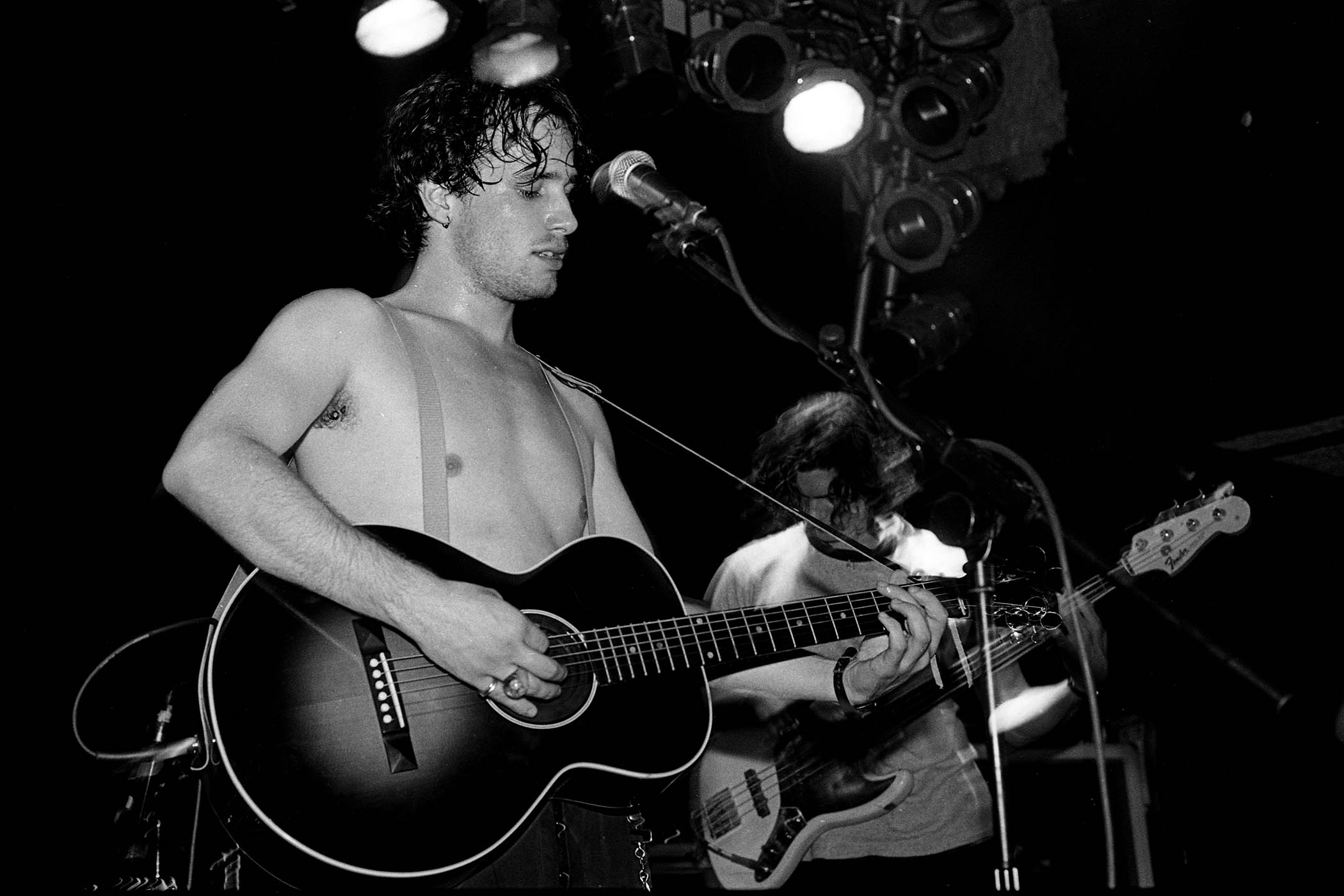

Buckley on stage in London in 1994

Guibert has long been assiduous about her son’s legacy. I first met her in London in 2003: the Garage in Highbury was the venue for a tribute gig to Jeff Buckley, with young British artists such as Ed Harcourt and Jamie Cullum paying homage. Guibert, then 55, was on stage, thanking the audience and performers. “I’m doing what no mother should have to do,” she said, through tears. When I remind her of that night, Guibert nods. “That is actually an encapsulation of my life.”

Trying to protect Buckley’s work “from being commercialised and corporatised” became Guibert’s “one and only goal”. Over the years, that has meant resisting the music and film industries’ attempts to exploit her son’s back catalogue and the burnishing of his legend. The latter has happened anyway.

“We have very surreptitiously,” begins Guibert, laughing delightedly, “very subversively, created and amassed what any marketeer would love to have: a massive, pent-up demand. A grassroots following that could not be created by any ad campaign, I don’t care how many millions of dollars you put into it. I’m good at what I do, and I believe my instincts have been borne out. This documentary, had it been created at any other time, would have been very nice and seen in arthouse [cinemas] and maybe owned by a few thousand people. But it’s the next generation, Gen Z,” she continues, “who have said: ‘Oh no. This music captures me.’”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

As the documentary title – taken from a lyric in one of Buckley’s greatest songs, Lover, You Should Have Come Over – has it: it’s never over, as is evident in Gen Z’s embrace of Buckley. He and his songs are all over TikTok. On social media young fans post pictures of their Jeff Buckley tattoos, or videos of themselves making pilgrimages to his old haunts, or performing covers of All Flowers in Time Bend Towards the Sun, an unfinished and unreleased duet with ex-Cocteau Twin Elizabeth Fraser, with whom he had an intense love affair (Berg says the Scottish singer was the only person she approached who declined to be interviewed for her film).

What’s next? In terms of unreleased recordings – All Flowers in Time Bend Towards the Sun aside – Guibert says the cupboard is pretty much bare. There is The Last Goodbye, an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet set to Buckley’s songs, that she would like to see more widely staged. And there are, still, conversations about a biopic, with Pitt’s production company Plan B occasionally checking in. “I’m making one last attempt to make a feature-length film about Jeff – while I’m still here! I would really like to do that before I go. I want it to be a kind of a biopic that no one has ever seen before. I want it to be really imaginative and creative and aesthetically different.”

How does Mary Guibert herself memorialise her son? Well, every year on his birthday, 17 November, she attends a tribute at Uncommon Ground, a restaurant and music venue in Chicago. This year will mark what would have been Buckley’s 60th birthday. (“That makes me so old! Astonishing!”)

“But, you know, for a mother, every day is mourning day. There’s not a day that goes by,” she says, through tears. “Not a single day.” The music, though, keeps her going. “As long as there’s some gal or a guy in a nightclub somewhere, trying to sing, over the clinking of glasses and dishes, one of Jeff’s songs – that’s the biggest tribute we could have. As long as someone is singing one of his songs, we’re good.”

It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley is in cinemas from 13 February

Photographs by David Tonge/Getty Images, Martyn Goodacre/Getty Images, Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Michel Linssen/Redferns and courtesy of Magnolia Pictures