Where are we now, 10 years after David Bowie’s final farewell on 10 January 2016? When he released Blackstar, his trippy, uncanny, raw and unsettling final album, on his 69th birthday, I had no idea that the artist who lit up so much of my life would depart from it two days later. If I now understand that Blackstar was a very knowing, generous and eerie goodbye, it took a while to accept his literal death. The crazed youthful hedonism of the bisexual alien rock star from Mars and Beckenham (no eyebrows, lashings of mascara, red spiky mullet hair) had to fight it out in my mind with the stark truth of Blackstar’s message. It is the title’s track’s spectral refrain – ah-ah, ah-ah – alongside Donny McCaslin’s sublime saxophone, that stays with me.

Bowie was an artist who had staged many resurrections. Aladdin Sane rose from the ashes of Ziggy Stardust and then morphed again (sleeker quiffed hair) to find a more soulful mood in albums such as Young Americans, through to the more austere, experimental Heroes and onwards. But the hardest persona to figure out was one closer to himself. It always is. When asked in an interview how his next persona might shape up, he replied: “I am inventing me.”

Decades before Blackstar, when I was 13, I tuned in to Bowie singing Starman on Top of the Pops. There were crisps all over the carpet of the family living room and my mother was yelling at me to get out the hoover and turn off the TV. It was so thrilling to watch Bowie sing Starman to the nation, his arm draped around the shoulder of his lead guitarist, the gorgeous Mick Ronson from Hull. Yes, it was all about Bowie’s peculiar, distinctive voice, and the chorus, which I interpreted as him telling mum to let the children boogie instead of hoovering the carpet. But mostly it was about the invigorating new mood that Bowie was creating. Ronson, blond feather haircut and tight gold lamé suit, seemed somewhat awkward and shy, which was a change from the machismo of most other rock guitarists. Starman pierced grey, dreary 1970s Britain with its cool, crazy narrative. To think that in the suburbs of North Finchley, which is where I lived, it was possible that “if we can sparkle” the Starman might “land tonight”. Yes, I wanted him to land in our little rain-soaked garden, to crush all the daffodils and take me to another life.

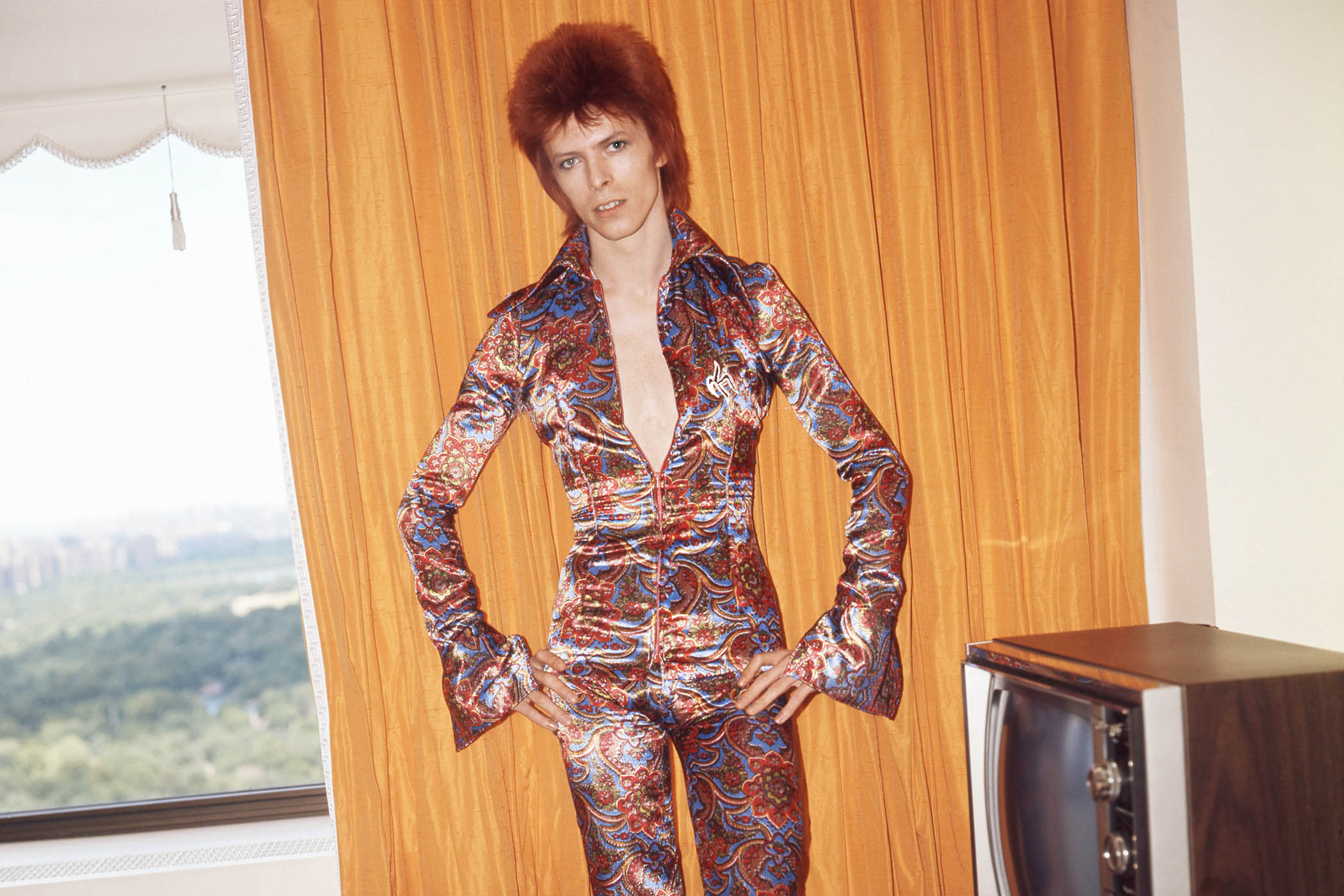

Bowie in full Ziggy Stardust regalia in a New York hotel room in 1973

If Ziggy Stardust entered my imagination and has never left the building, it’s because his hysterical, poetic, stylish, sexy exuberance in music and fashion shook up the story we had been told was our lot. Glimpsing Ziggy was the equivalent of someone from 1907 seeing a cubist painting for the very first time. To get a taste of what Bowie was up against in 1973, the TV talk show host Russell Harty, who was supposed to represent the voice of outraged middle England, interviewed Bowie in a friendly but spiteful tone. The alien rock star’s mesmerising beauty was a gift to the camera: high cheekbones, alabaster skin, long neck, the English teeth that would later be replaced with an American set, those otherworldly green and blue eyes. When asked whether he believed in God, Bowie was obliged to confirm he believed in “an energy form”. Did he indulge in any form of worship? Bowie, softly spoken and charming, replied: “Life. I love life.” At one point, Harty, who was gay (though we were not supposed to know that), pointed to Bowie’s feet, which were adorned in high-platform yellow and orange strappy shoes. “Are they women’s shoes or men’s shoes or bisexual shoes?” Harty was keen to know. Bowie replied: “They’re shoe shoes, silly!”

We all wanted at least one pair of shoe shoes to walk away from the flattening masculinity and crushing femininity we were supposed to learn how to perform. In this sense we already understood the societal obligation to create personae that might not fit us, so when Bowie created Ziggy, it was an invigorating provocation. We felt understood. It was up to us to find the point to our lives, but in the meantime we poured all our teenage longing into Ziggy and danced to Hang On to Yourself at every disco. Our clothes became more experimental, we knew all the words to Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide and sang it while we waited for the night bus at 2am. When it seemed likely that the misty London night had swallowed up the non-existent bus, its chorus, “Oh no, love, you’re not alone” and refrain, “Oh, give me your hands”, helped us believe that somehow we would make it home before the milkman turned up at our doorstep in his electronic float.

I wanted him to land in our rain-soaked garden, crush the daffodils and take me to another life

I wanted him to land in our rain-soaked garden, crush the daffodils and take me to another life

To wear one earring in the early 1970s was considered freakish, as was Bowie’s desire to look “like a cross between Nijinsky and Woolworths”. This look was within our reach: we could afford Woolworths, and anyway, paste diamond jewellery could be found in every charity shop on the high street. A friend who has known me since I was 14 told me recently that I had a poster of Nijinsky on my bedroom wall in North Finchley. I have no memory of this; really I knew nothing about him. So I can only think that Bowie, who was arty, had lifted me from Tally Ho Corner, midway between North Finchley and Whetstone, to Nijinsky dancing in Paris for the Ballets Russes. Later though, I was a fan of the dancer and choreographer Lindsay Kemp, with whom Bowie took dance lessons.

Bowie’s genius was that we created Ziggy as much as Ziggy created us. His sophistication as a writer, musician and performer made a space for us not so much to invent ourselves as to find the daring that was already lurking inside us. Reality was so dull; we needed stardust, glitter and artifice. His music somehow spoke to the reality of everyday life but lifted us up from it. The late, great photographer of all things rock ’n’ roll, Mick Rock, said it best about Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust days: “He was projecting powerfully.”

Yes, and we projected right back. Although I appreciated Bowie’s glam rock contemporary Marc Bolan (no one could simper so perfectly) and liked his dreamy Life’s A Gas, he did not project powerfully enough.

Related articles:

It is no wonder that Bowie had to kill off Ziggy, just as replicant humans had to be retired in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. They had become too powerful. If those replicants were bio-engineered by the fictional Tyrell Corporation, it was the very real and talented Suzanne Fussey, the future wife of Mick Ronson (later known as Suzi Ronson), who created Ziggy Stardust’s iconic extraterrestrial mullet and dyed it Schwarzkopf Red Hot red. At the time she was a plucky young hairdresser in a high street salon in Beckenham, still living at home with her parents.

Bowie in a promotional shot for Blackstar, which was released two days before he died

Time passes. Ageing is a metamorphosis we do not really want, though it’s nice to occasionally buy a cola-flavoured vape at the newsagent without being asked for ID. Yet, it seems to me that it is the older Bowie who truly landed his genius – despite the whop whop whop of his golden years. I have never loved him more than when I first listened to Where Are We Now?, the lead single from his 25th studio album, The Next Day. There was no prior publicity for its release in 2013, but this melancholy, reflective song in search of lost time, particularly his years living in Berlin in the late 1970s, could be discovered by fans on iTunes.

He was 66. The title itself was asking the same question I was asking too. There really is no writer or artist with whom I can better measure my own life and preoccupations, from when I was 13 and onwards to Bowie’s untimely death from cancer. I regard Where Are We Now? as a masterpiece; the cadence and phrasing, the collaging and collapsing of past and present. The line “the moment you know you know you know” is just enigmatic enough to make it unforgettable. The extraordinary video for the song – directed by Tony Oursler, an artist I have long admired – shows black-and-white footage of the Berlin Wall in the 1970s and then the elation of people crossing the border when it fell in 1989. We are invited to mostly focus on the serene and stark face of Bowie and his contemplative companion, the artist Jacqueline Humphries. Their faces are superimposed on to tiny puppets, sitting side by side on a suitcase. Here, Bowie seems closer to himself: older, sadder, stronger; less ego, more love. And it reached number six on the UK singles chart.

The spacesuit of an astronaut haunts the official video for the song Blackstar. Where is the body? We discover there is a jewelled skull inside the spacesuit. Perhaps this is a nod to the lost astronaut of Space Oddity, Major Tom, who sends messages home as he orbits Earth. Or is it there to signify Bowie’s final liftoff? A smiley face badge is wittily pasted on to the astronaut’s jacket.

Photographs by Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns/Gettyimages, NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images, Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, Jimmy King

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy