Photographs by Sophia Evans for The Observer

There are places in a city that announce themselves and others that are slowly revealed. The Premises, on a quiet corner of Hackney Road, belongs to the second category. From the street, it looks like an ordinary neighbourhood cafe: bottle-green frontage, a few bistro tables outside, the low-level murmur of tea drinkers, people passing through. But musicians arrive with guitar cases and sound engineers slip in at odd hours. Tour vans idle discreetly on the side street. Something else is happening here.

Inside, the eye takes a moment to adjust. The room has a familiar vernacular: laminated menus, a tiled counter, sunlight catching chrome napkin holders – but then you notice the walls. They are covered almost entirely in a dense constellation of framed photographs. Not a curated few, but dozens upon dozens: Nina Simone alongside Lana Del Rey, Gladys Knight and Thom Yorke, Amy Winehouse, Dave Brubeck, Chaka Khan, Dua Lipa, Nick Cave, Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def). The pictures are accompanied not just by a signature, but messages – handwritten notes of gratitude, affection, encouragement. “To everyone here – thank you for feeding us”; “We love The Premises. Until next time.” It dawns on you that this is no ordinary caff.

At its centre are siblings Ali and Nural Acil, who have owned and run The Premises cafe for 25 years. Their warmth is the first thing most people notice: they have the attentive ease of hosts who genuinely like the room they’ve built. They move between tables with an unhurried efficiency that comes from knowing most customers by name. Nural asks how you are while carrying plates in both hands, memorising your order along with the three she took before you. Ali wipes a table, checks the coffee machine, and answers a question from the kitchen – barely pausing between tasks.

The day menu is broad: panini, pancakes, Turkish menemen, eggs done any way you want them. But the real star is the full English. Customisable and totally unpretentious – crucially, with the option of fried bread on the side, that increasingly endangered species of cafe cooking – it is available here without apology. Builders, musicians, neighbours and teenagers lean over the same tables. From 5pm, the cafe shifts into a bistro serving Turkish and Mediterranean dishes that reflect the owners’ heritage: grilled octopus, moussaka, kofte. The lighting softens, the smell of aubergine and grilled peppers replaces toast, but the welcoming atmosphere is constant.

The Premises on Hackney Road, east London. Main image: Nural and Ali Acil, who have owned and run The Premises for 25 years

What many first-time visitors don’t realise is that, beyond the smell of coffee and sound of spitting fat, a back corridor leads to one of London’s most beloved music studios. The Premises started life in the 1980s in a neighbouring building founded as a rehearsal space by jazz musicians Colin Dudman and Dill Katz. By the mid-90s the business faced administration, and was taken over by Viv Broughton, a former drummer of the Pretty Things who subsequently helped launch the Voice newspaper. Broughton, now 82 and wearing jeans and Chelsea boots when I meet him, has grown the business from a ramshackle operation – that somehow hosted early Britpop outfits Blur and Suede – into the greatly expanded modern complex that exists today.

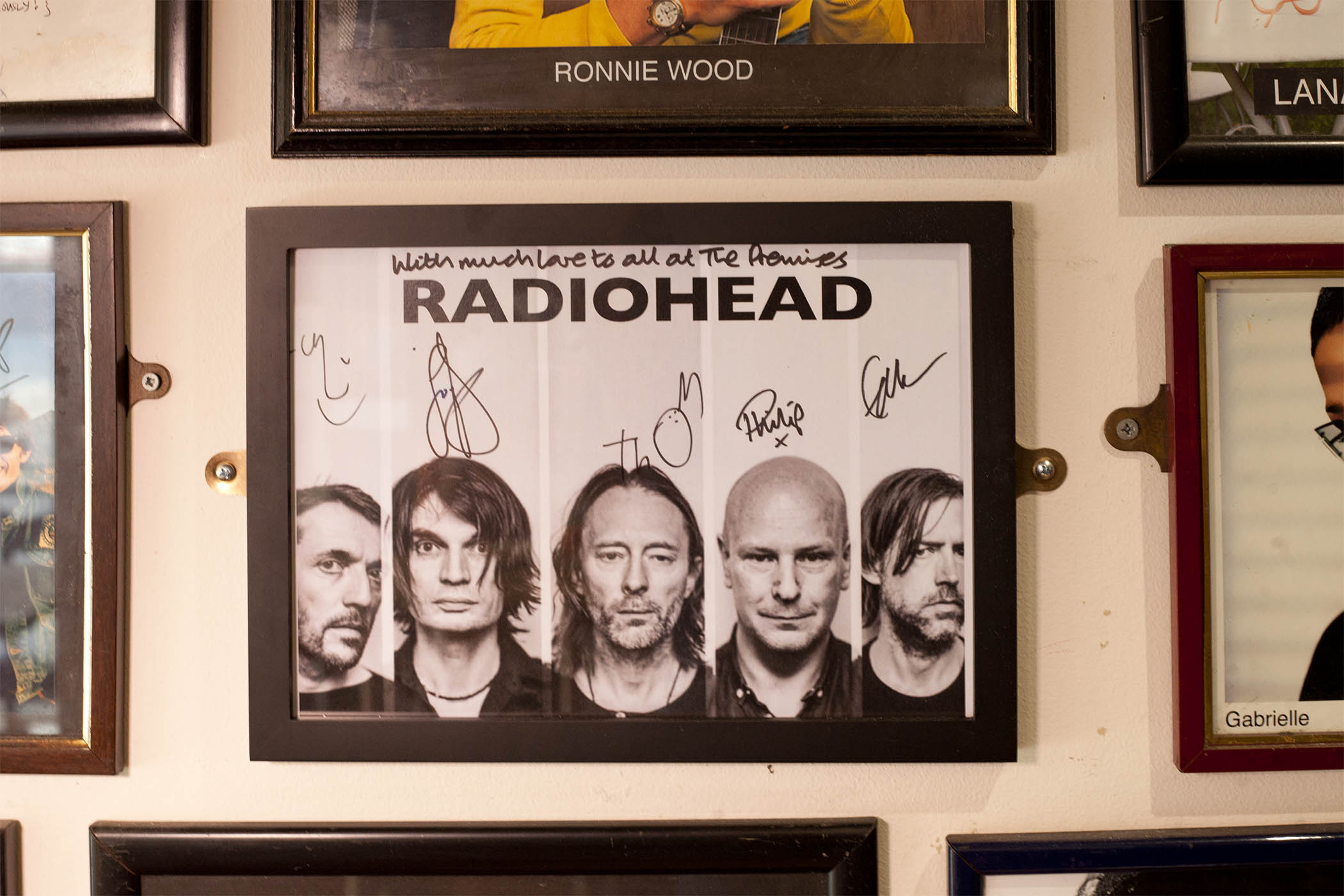

“The bailiffs were taking a Steinway out when I decided that I can’t let this happen,” he tells me from his upstairs office, surrounded by boxes of records. “It’s been a long hard slog to get it to this level, but now it seems to be almost fully booked every day. We just had Radiohead in for a couple of weeks, Beverley Knight was in last week. We’re getting major artists coming through now.”

Today’s iteration of The Premises spans multiple addresses, which Broughton describes as “an ecosystem of musicians, bands, producers and songwriters” that includes 24 studios as well as a hairdresser and a clothes shop. But the cafe is best known. “People think The Premises is a cafe with a studio attached,” Broughton says, “but it’s really a studio complex with a cafe that is open to the public, so the cafe is hugely important.”

‘With much love to all at The Premises’: a message from Radiohead

The studios are a space where long days unfold; where musicians shape and reshape their records. But when they break for lunch, they enter a place of care and relaxation, where the portions are never small and new collaborations begin over tea.

When I meet producer and musician Nicky Brown in the cafe, he is sat with Eitan Lee, a photographer and documentary-maker who lives on nearby Columbia Road and claims he is “50 per cent” food from The Premises. Brown and Lee have been regulars since the cafe opened and best friends for just as long. “If you tell almost any musician in the business, ‘My studio is in The Premises’, they’ll go, ‘Oh, yeah, that place is great, and the cafe’s slamming!’” says Brown, who has rented a studio here since the beginning. “Viv’s ethos is really strong. He just wants a place where musicians can meet, have a good time and relax.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

We are soon joined by Brown’s son Matty, who practically grew up in The Premises. Now 28, he is a successful musical director and drummer, just returned from touring with Sugababes and Stormzy. “Coming here as a kid to visit my dad, I was surrounded by so much culture and music,” he recalls. “The highlight was looking for any new pictures on the wall and almost always seeing artists that I looked up to.”

Nural and Ali have witnessed Matty’s journey into adulthood, as they have many of their regulars. “It’s like a family,” Nural tells me in a quick break between serving tables. “I know many musicians, and I’ve known them for a long time. We catch up, they tell us stories from their tours.” Earlier this year there was an emotional reunion with Patti Smith, who Nural had not seen for 20 years but who returned to the cafe for a book signing. “We were both older, but we hugged, we spoke and she introduced me to her son.” Ali adds: “Whether it’s musicians or customers we have relationships that are more than two decades old.”

And so the cafe and the studios function as one. The priority has always been the work: rehearsal rooms that can accommodate the world’s biggest acts while remaining affordable for musicians who are just starting out; studios that are well engineered but not intimidating; a cafe where you can sit for 10 minutes or three hours without anyone nudging you to leave.

Hannah V, a Grammy-nominated pianist and composer who has rented a studio for eight years, describes The Premises as “one of the crucial, unseen pillars” of London’s music industry whose support is critical to the overall health of the scene. “There’s such a trickle-down effect because we open our doors to other people, to other creatives, who come here and use the studios but also meet people,” she says. Brown recalls one such chance meeting with Paolo Nutini, who was invited to the studio of fellow producer James Ford more than a decade ago. “I didn’t recognise him at first and told him he looked just like Paolo Nutini, which was embarrassing,” laughs Brown. “But we got chatting and then he invited me to work on four tracks for Caustic Love.”

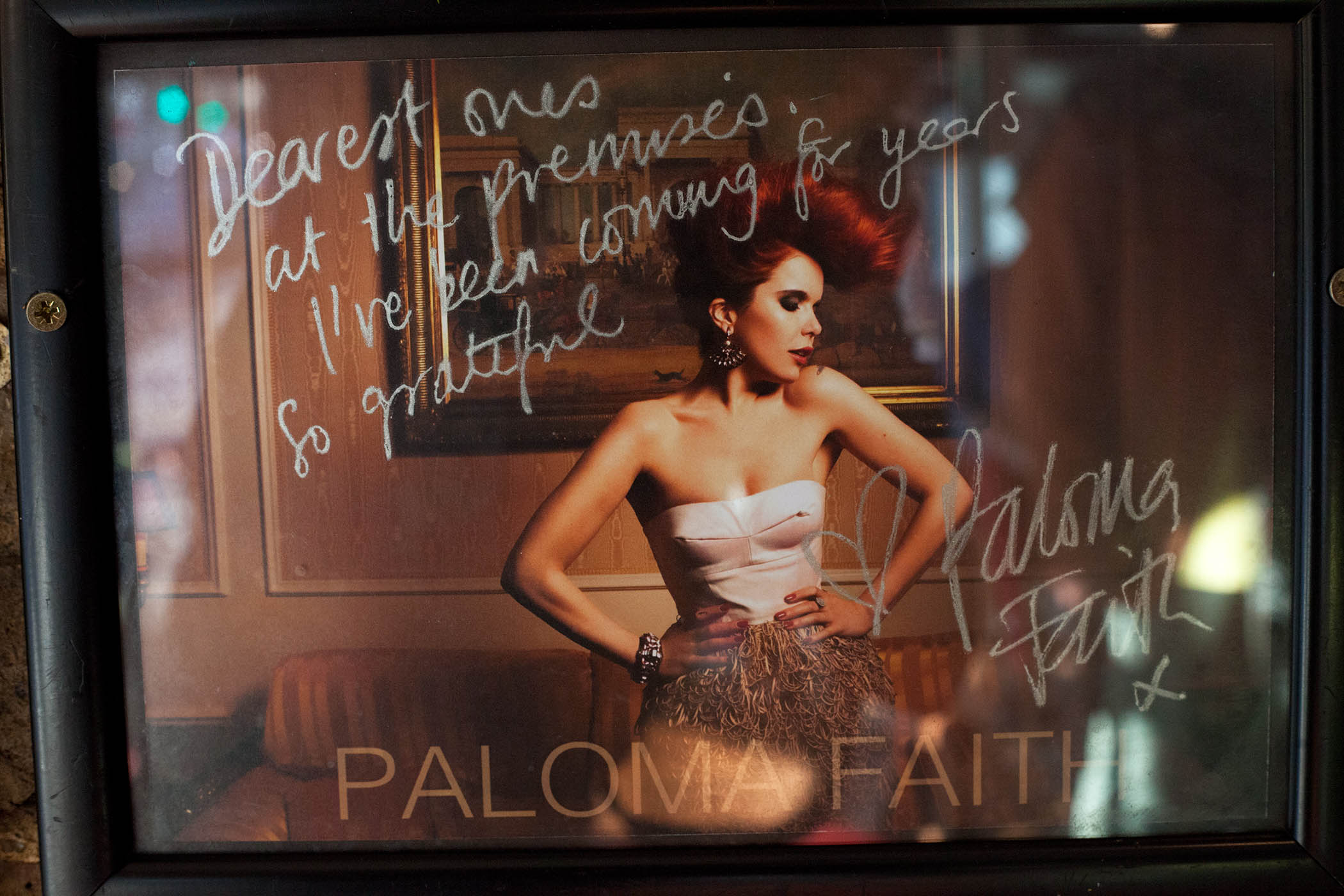

‘I’ve been coming for years. So grateful’: a poster on the wall signed by Paloma Faith

The building has seen London change around it: the slow creep of steel and glass; the branding of neighbourhoods; cultural spaces becoming prohibitively expensive. But The Premises has continued to offer an environment for a kind of cross-pollination. “What we’ve established here is a seven-day-a-week art centre that operates entirely self-sufficiently,” says Broughton. “It’s a business model for how an art centre can function without being subsidised, and I don’t think there’s anything like it anywhere in Britain.”

Broughton recalls the day Nina Simone turned up at The Premises. She arrived in a limousine wearing a full-length fur coat, matching hat and huge dark glasses; her cancer had progressed to the stage that she was using a wheelchair, pushed by her chauffeur, who was dressed in all-white regalia. “We were terrified, of course, because she had this reputation of being … volatile, shall we say,” he says. “But she was as sweet as anything and I just managed to get her to sign that lovely photograph that’s in pride of place downstairs.”

In all my conversations about The Premises, the word “vibe” crops up repeatedly. In a city where creative work is increasingly forced into the margins – priced out, pushed on, or flattened into something tidy – The Premises remains unvarnished. It is not trying to be discovered. It does not trade on legend. It is simply open: to whoever walks in hungry or needs the time to make something, to anyone who didn’t mean to stop but finds a reason to stay.