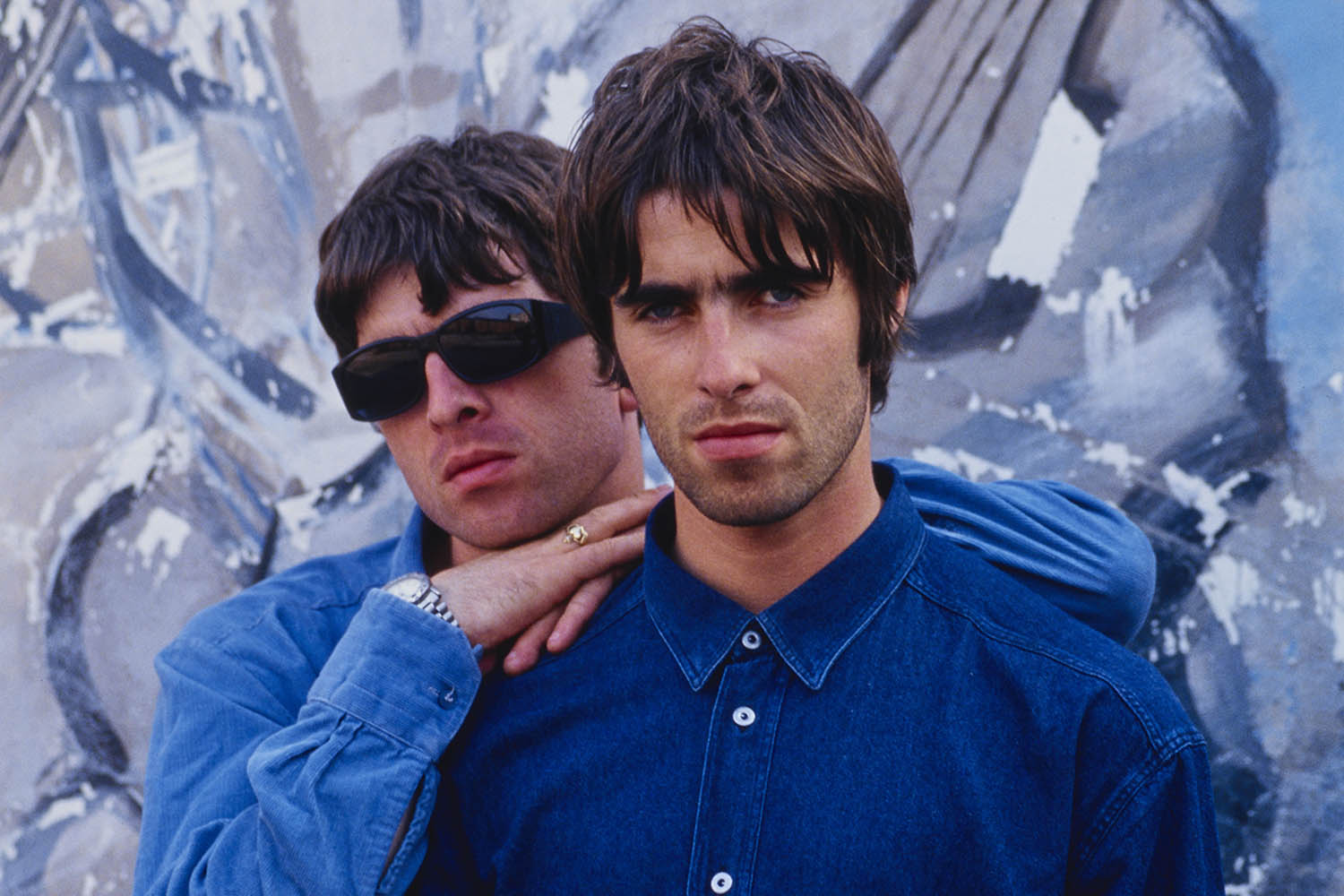

Last year, on 27 August, the end of a 15-year war was announced on social media. “The guns have fallen silent,” declared Oasis’s accounts, with no little bombast. “The stars have aligned. The great wait is over. Come see. It will not be televised.” On 4 July, a reunited Oasis will play the first of 41 scheduled gigs as a band once again, a hell-freezing-over scenario many fans doubted would ever happen, given the levels of rancour between the band’s frontman, Liam Gallagher, and his older brother, guitarist Noel. A lot of the fighting was public – “tofu boy”, “potato”, “former brother” and “a man with a fork in a world of soup” were some of the funnier barbs traded.

The senior Gallagher had been particularly unequivocal about the band being over. “If I was to get Oasis back together tomorrow and then do a tour, I’d have $100m in the bank but I’d have learnt fuck all,” Noel told Q magazine in 2017.

“If I had 50 quid left in my pocket, I’d rather go busking,” he told Mojo the following year.

Theories abound about the reasons for Noel’s change of heart. Some point to his split from his partner, Sara MacDonald, to whom he was married for 12 years. Liam’s need for his brother, meanwhile, was arguably at an all-time low. The younger Gallagher had played two sold-out gigs at Knebworth in 2022 as a solo artist and toured in 2024 to mark the 30th anniversary of Oasis’s Definitely Maybe – without the rest of Oasis.

Whatever the motivation, the floodgates have been opened on all things Oasis, dovetailing into a wider 1990s revival in which younger people, in particular, are looking back with envy at a time before phones had cameras.

These high waters carry upon them a number of books, two of which claim to have been in the works since before the reunion announcement: PJ Harrison’s Gallagher: The Fall and Rise of Oasis and A Sound So Very Loud: The Inside Story of Every Song Oasis Recorded by Ted Kessler and Hamish MacBain. In the latter we find Kessler – in 2016, as acting editor of Q – hanging out with Liam Gallagher, a man he had interviewed many times before, including for The Observer in 2002. In the pub, they’re dissecting the pre-release screening of Supersonic, the soon-to-be-released Oasis documentary. Liam has issues, but he can 100% endorse the bit where Noel compares himself to a cat and Liam to a dog.

“Without a doubt,” agrees Liam, getting into the kind of bullish, savant stride that sold millions of copies of music weeklies and men’s monthlies between 1994 and the internet age, and newspapers both tabloid and broadsheet. “He’s arrogant, sticks his arse up, comes and goes as he pleases, stands apart, just surveying everyone. Loves being stroked. Total tart. Loves you when he wants. I only get took out on a lead. I’m not allowed on the sofa. I run around with the pack, barking, tongue hanging out. He’s all aloof up there watching, licking himself and plotting. That’s us all right.”

Oasis were – are – a band that served as a kind of lightning rod for all sorts of binaries, both real and convenient, to which “cat” v “dog” is just a sideshow. Oasis represented the north; many of their fellow Britpop-era bands were from the south (Pulp the obvious exception). Oasis were football terrace; their biggest rivals were art school. Oasis were direct, no-nonsense and ambitious when many around them were apologetic and disdainful of the mainstream.

A 2024 mural by Pic.One.Art on the side of Sifters Records in Burnage, Manchester

Within the Burnage quintet, Noel was the clever one who wrote all the songs, and Liam was his live-wire liability of a brother, a glowering pin-up whose appetite for destruction was equal to his love of John Lennon; a teenager who was hit on the head with a hammer and discovered that music was the equal of football.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

More widely, there was a greater dichotomy – “us” v “them”, Britpop v grunge; the attempt to get music fans to buy British, rather than American goods; and a summoning of the spirits of the ancestors to bolster the flag-waving. When Oasis’s single Roll With It was released in 1995, Damon Albarn of Blur told a radio DJ it sounded like “Quoasis” [after Status Quo]. Oasis got “Quoasis” T-shirts printed. In 1994, The Face had dubbed Oasis “The Sex Beatles”, homing in on how Oasis delivered 1960s melodies with John Lydon’s sneering death stare.

One of the best books about the era is the late David Cavanagh’s The Creation Records Story: My Magpie Eyes are Hungry for the Prize, a warts and more warts biography of Oasis’s record label. Oasis turn up at the 11th hour, on page 409. The book’s title comes from a song by Creation signing the Loft, another band who have reformed in 2025, to a somewhat more muted response.

Although it disdained greed, the Loft lyric was emblematic of 1990s-era Creation and its mercurial boss Alan McGee, who correctly saw in Oasis a band as ambitious as he was. And in Oasis capo Noel Gallagher, McGee had spotted a magpie with especially silky skills; one who didn’t mind cracking open other people’s songs for the riches contained within. T Rex were mined for Cigarettes & Alcohol; Slade and the Rutles were other protein sources. Noel’s strongest suit, in addition to his long-range strategic vision, was his directness. He gladly owned up to the retro bricolage – and indeed John Robb, in another new book on Oasis, Live Forever: The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of Oasis, details the younger Noel’s appetite for greatest hits sets. You go straight to the best stuff, don’t you?

All of these binaries swirling around Oasis were both true and not the whole story. The younger Gallagher, for one, often knew exactly what he was doing: Liam even gave his stage presence a name – “stillism”.

A Sound So Very Loud, co-written by Kessler and his former NME colleague MacBain, tells the tale through a deep dive into every Oasis song ever released, with interludes for anecdotes they have harvested from their years within the Oasis fold. Kessler was on NME duty in 1994, when the Gallaghers fell into the laps of the music press, motormouths with no thought to consequences; the younger MacBain was a superfan who successfully lobbied to be granted an interview Oasis in 2006 and ending up being papped alongside Noel Gallagher in a state of disrepair in a newspaper gossip page.

It’s a two-voice, episodic narrative that nonetheless tilts at a kind of completeness in its many tangents and contexts; about, for example, the band’s key relationships with Johnny Marr and Paul Weller. The authors identify exactly how the Supersonic documentary brought a rabid new audience to an old band then on seemingly indefinite hiatus, an audience who were toddlers when the younger Gallagher threw a plum at his big brother and then tried to brain him with a guitar backstage at a festival in Paris in 2009 – the brawl that ended the band, until now.

Robb is also deeply embedded: a musician, journalist and face-about-Manchester whose band, the Membranes, used to rehearse in the same Boardwalk practice rooms as the nascent Oasis. He was present at the start of the infamous fight at Rockfield studio in Monmouthshire when Oasis were recording (What’s The Story) Morning Glory that resulted in Noel briefly quitting the band. Robb’s book may be “unauthorised”, but he is the scribe Noel turned to when he wanted to be interviewed on the eve of this long-awaited tour.

Robb writes with a deep understanding of Oasis as a world-beating product of Manchester, that most musical city. They were formed by Buzzcocks, Factory Records, the Smiths, the Haçienda, Hulme squat raves, the Stone Roses and their Irish roots. South Manchester was a deeply Irish enclave and Robb locates the Gallaghers in a long tradition of Anglo-Irish epoch-makers with a distaste for the establishment: Lennon and McCartney, Morrissey and Marr, Lydon. Even Ed Sheeran, without the rebel bona fides, declares himself “culturally Irish”.

Noel is arrogant, sticks his arse up, comes and goes as he pleases, stands apart, just surveying everyone. Loves being stroked. Total tart

Noel is arrogant, sticks his arse up, comes and goes as he pleases, stands apart, just surveying everyone. Loves being stroked. Total tart

Gallagher, by PJ Harrison, takes a different tack. Harrison is younger than all of the other writers, a 1990s teenager from the north-west alert to the possibilities Oasis’s music invited him to seize; he later spent some time on the band’s fringes. He collared Andrew Loog Oldham in an airport and persuaded the erstwhile Rolling Stones manager to write him a (very short) foreword. The Gallaghers might well approve of this outsider’s cheek.

The main thrust of Harrison’s book is the wilderness years, between the band’s bitter 2009 implosion and the announcement of this year’s reunion. It is written in alternating Liam and Noel chapters, with a detour into the band’s heyday.

All three books, though, suffer from the kneejerk assumption that the question of Oasis’s musical greatness is moot. It’s easy to understand the amped-up appeal of the band’s first two albums, even if your own tastes extend beyond the overdriven guitars and melancholy-wrapped-within-aggro approach of Oasis’s core offering. Kessler and MacBain particularly have to grind through the band’s wildly patchy post-Be Here Now oeuvre with the semblance of a straight face. Someday, a more dispassionate take on the band might follow John Harris’s The Last Party: Britpop, Blair and The Demise of English Rock, his 2003 overview of the Britpop years. None of these three books really comes to grips, either, with the uglier side of the hyper-masculine confrontations the brothers stood for and enabled in their followers.

Interestingly, Harrison – a superfan – should be blind to the brothers’ failings, but most often calls out bad Gallagher behaviour. He is attuned to the trauma in their childhoods, wonders whether Liam has social anxiety and ADHD, and is interested in the many women in the Gallaghers’ lives, including two daughters who Liam refused to acknowledge for years. As armchair analysts go, he is thoughtful about the many ongoing echoes of the damage done by Tommy Gallagher, the brothers’ violent, alcoholic father.

Harrison’s latter-day timeframe may appeal to relative newcomers and those, including Robb, who feel Oasis are the last truly era-defining band standing, a group from the days before gaming took over as young men’s preferred leisure activity. There have been other major British guitar bands since, of course – Arctic Monkeys, for one, and various arena-filling acts who have inherited the Oasis demographic, such as Catfish and the Bottlemen – but none with a stranglehold on the zeitgeist like Oasis had in the 1990s.

Oasis’s level of fame meant that, for their biographers, their output, movements, decisions and utterances take on a mythic quality. What emerges from reading all three books is a portrait of a national obsession that is gently distorted, like an over-flattering clothes-shop mirror. Oasis were a band as divisive as they were uniting, instinctively tribal, even if that tribe swelled into the many millions. Famous, powerful men are forgiven a lot. Their more poisonous pronouncements were often a cause for dismay to the many people not swept up by the cocaine-dusted hedonism that became allied to the hope and promise of the late-1990s Labour government.

Harrison provides one key detail that the other books miss. In 2025, the publishing rights to Oasis songs held by Sony revert to Noel Gallagher. The cat, you might think, has played a very long game, in the interests of what is sure to be quite a lot of cream.

A Sound So Very Loud by Ted Kessler & Hamish MacBain (Pan Macmillan, £25). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £25.

Gallagher by PJ Harrison (Little, Brown Book Group, £22). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £22.

Live Forever by John Robb (HarperCollins Publishers, £22). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £22.

Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Kevin Cummins/Getty Images, Christopher Furlong/Getty Images