I first met Martin Parr, who died on Saturday, aged 73, at his home in Bristol, when he curated the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in 2004. In retrospect, it was the perfect context in which to cross paths with a singular photographer who was also a force of nature when it came to championing the medium in all its forms: exhibitions, festivals and, above all, photobooks.

At Arles, he set a high standard for wildly imaginative curation that has not been equalled there since. He showed work by venerable documentarians Chris Killip and Tony Ray-Jones, as well as emerging talents like Ewen Spencer, and created an entire section devoted to vernacular photography, which ranged from found family snapshots to clandestine images of life in the Lodz ghetto.

Children in New Brighton, Merseyside, from Parr’s pivotal 1986 collection The Last Resort

An unforgettable evening event introduced me – and I would imagine the majority of the packed audience in the Roman amphitheatre – to the wonderfully surreal world of the magazine Useful Photography. It was a deadpan celebration of the visually mundane in all its oddness, from the garish images of cooked meat that adorn late-night kebab shops to the archive of a council clerk whose job it was to photograph flyovers in various stages of construction. In short, it was pure Parr: serious, funny, engaged and a little bit odd.

In the flesh, Parr looked like he belonged to another time and place: the postwar suburban England he grew up in. But he was incredibly knowledgable about photography, both historical and contemporary. Another year, at Arles, he enthused to anyone who would listen about a book, The Afronauts, by a then little-known photographer, Cristina de Middel. It duly became a self-published phenomenon.

A fair in Sedlescombe, Sussex, in the late 1990s

Put simply, Parr kept up, but one sometimes sensed his interest in the new, like his avid collecting, was at least in part driven by a fear of missing out. There was no doubting his support for younger photographers whose work he liked, his endorsement alone creating a buzz within the small, interconnected world of British photoculture.

For all that, there was a sense of old-fashioned – and emphatically English – otherness about Parr, which was surely rooted in his upbringing in Epsom, Surrey, where his father, a civil servant, introduced him at a young age to the joys of birdwatching. If documentary photography is at heart an exercise in patient attentiveness, that was perhaps the perfect apprenticeship.

The mayor of Todmorden's inaugural banquet, from Parr’s series The Non-Conformists

Parr took up photography in his early teens, sensing immediately that he had found his vocation. In 1970 he enrolled at Manchester Polytechnic, finding a kindred spirit in Daniel Meadows, with whom he worked at Butlin’s in the summer holidays as a roving photographer. In one of many tribute postings on social media after his death, the writer and curator David Campany alluded to his preference for Parr’s early, less well-known, black-and-white work. Having been by turns surprised and entranced in 2013 by an exhibition of Parr’s 1975 series The Non-Conformists, I’m inclined to agree. It features quietly observant monochrome shots of worshippers at various Methodist and Baptist churches in and around Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. In its quietude alone, it is the antithesis of the later and louder colour work that became his signature and his brand.

Tucking into a doughnut in Ramsgate

That style emerged in all its in-your-face bashness 11 years later with the publication of The Last Resort, which, in its own way, was as pivotal as Chris Killip’s In Flagrante or Paul Graham’s Beyond Caring in defining a new wave of British documentary photography in that decade. Shot in New Brighton, Merseyside, while Parr was living in nearby Wallasey, it divided critical opinion with its depiction of northerners at play by the sea. Parr’s sin was that he was not just an outsider, but a southern one with an acute eye for atmosphere and telling detail. He went in close and accentuated the brashness and colour and even the drabness of British seaside culture to a degree that some found grotesque and demeaning of the working class. The passing of time, though, has imbued the images with a strange potency that now seems prescient.

I interviewed Parr on several occasions since that first meeting at Arles, and our paths crossed at openings and festivals over the years. He was always good company, an enthusiast and an advocate for photography, whose passion shone brightly. He was an inveterate collector as well as an obsessive photographer. In Arles in 2013, another exhibition featured two of his most cherished series of objects: tea trays adorned with tourist or advertising images and wristwatches bearing Saddam Hussein’s face. This was Parrworld in miniature, a precursor to the vast exhibition of the same name that the Baltic in Gateshead hosted in 2009.

Glenbeigh races in County Kerry, 1983

For me, as no doubt for many others, Parr was an invaluable source of information, alerting me, to give just one example, to the unsung genius of the Japanese photographer Akihiko Okamura, whose archive of images from the early days of the Troubles in Northern Ireland is revelatory. My abiding memory of Parr, though – apart from that long weekend in Arles more than 20 years ago – is of an afternoon I spent at his house in leafy Bristol a few months later. White-gloved, he laid out a selection of his vast photobook collection for my perusal, one rare tome worth somewhere in the region of £50,000. It was an extraordinary insight into the nature of his other obsession, but also his creative discernment and, above all, his passion for photography, especially in its most democratic form.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“The photographic book is a great teacher,” he said, “not least because it’s where photographers learn about photography. A book also ensures that the work lives long after a show, and, most important of all, perhaps, that the ideas travel. A book really is the perfect medium for images as well as words.”

Beachgoers queueing for ice cream in Tenby, 2018

He did more than anyone to promote that medium and to assert the importance of photography as an art form to a British public who, until relatively recently, seemed innately suspicious of images that were not monochrome and historical. It strikes me now that he is one of those rare characters who will be acutely missed because he is irreplaceable. And because it is hard to imagine the British photography community without him at its centre, cajoling, inspiring and sometimes holding forth like an inspiring scout master. The Martin Parr Foundation in Bristol will continue what he started way back when he picked up a camera in his teens. Even then, one suspects, he had one eye on posterity.

“Martin has left us despite being invincible,” Cristina de Middel posted on social media, speaking for his colleagues at Magnum, the photographic community here and abroad, and indeed anyone who had the good fortune to spend time in his company.

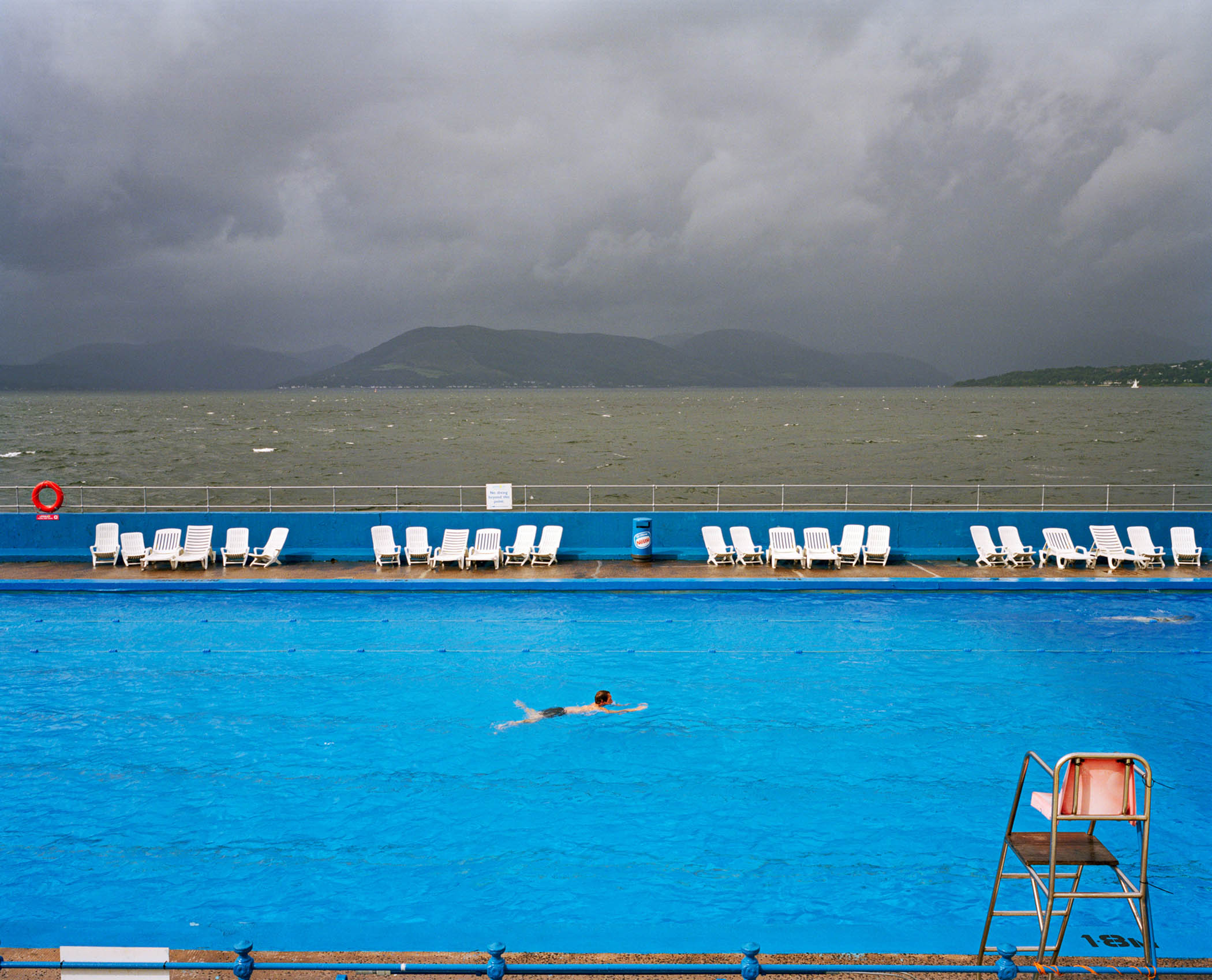

Grey skies over Gourock lido in Inverclyde, 2004

Photographs © Martin Parr/Magnum Photos