Related articles:

“Genius” is a tricky term, complicated by its forking and branching history. Originally it referred to a spirit, a genie like those that emerge from bottles to fulfil wishes in the Arabian Nights; in less superstitious times it has turned abstract and impalpable, allowing us to refer to the genius of a place, sanctified by its atmosphere. Genius assumed human form when it became an accolade bestowed on fearless artistic innovators such as Richard Wagner and James Joyce, or on scientists such as Einstein, whose frenetic hair seemed to vouch for the ferment in his white-hot brain.

But hyperbole has devalued the word by filling it with hot air: Apple’s Genius Bar usually turns out to be staffed by blinking nerds not technocratic wizards, and when Trump claimed to be “a very stable genius” he exposed himself as a mentally screwy, fatuously puffed-up dimwit.

Helen Lewis devotes her angry, witty book to a narrowly polemical account of the notion and its myth-making boosters. For her, genius is “a rightwing concept”, offensive “because it champions the individual over the collective”. This special category, “somewhere between secular saint and superhero”, is not democratically open to all, and the prodigies it celebrates are for Lewis “misshapen figures”, monsters who typically mistreat their wives, neglect their children and deny credit to their collaborators. The geniuses are all men, since women, as Lewis suggests in a glance at Jane Austen, lack the requisite swagger. I think she underestimates Austen’s sense of her own importance: she described novels, her own included, as “works in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed”.

Prosecuting her case, Lewis disinters some nasty and nonsensical theorising by the pseudo-scientists who have contributed to the myth. Darwin’s half-cousin Francis Galton, for instance, thought that genius was a matter of eugenics: he therefore proposed banning those with low intelligence from breeding and badgering them to emigrate. More recently, statistics persuaded the psychologist HR Eysenck that geniuses were likely to be born in February and to have high concentrations of uric acid in their bodies; it also helped if they happened to be Jewish. Rather than attributing high achievement to genetic advantage, Eysenck mused about “extraterrestrial factors”. The most rarefied minds, he suspected, were electrified by emissions from magnetic storms in the upper air.

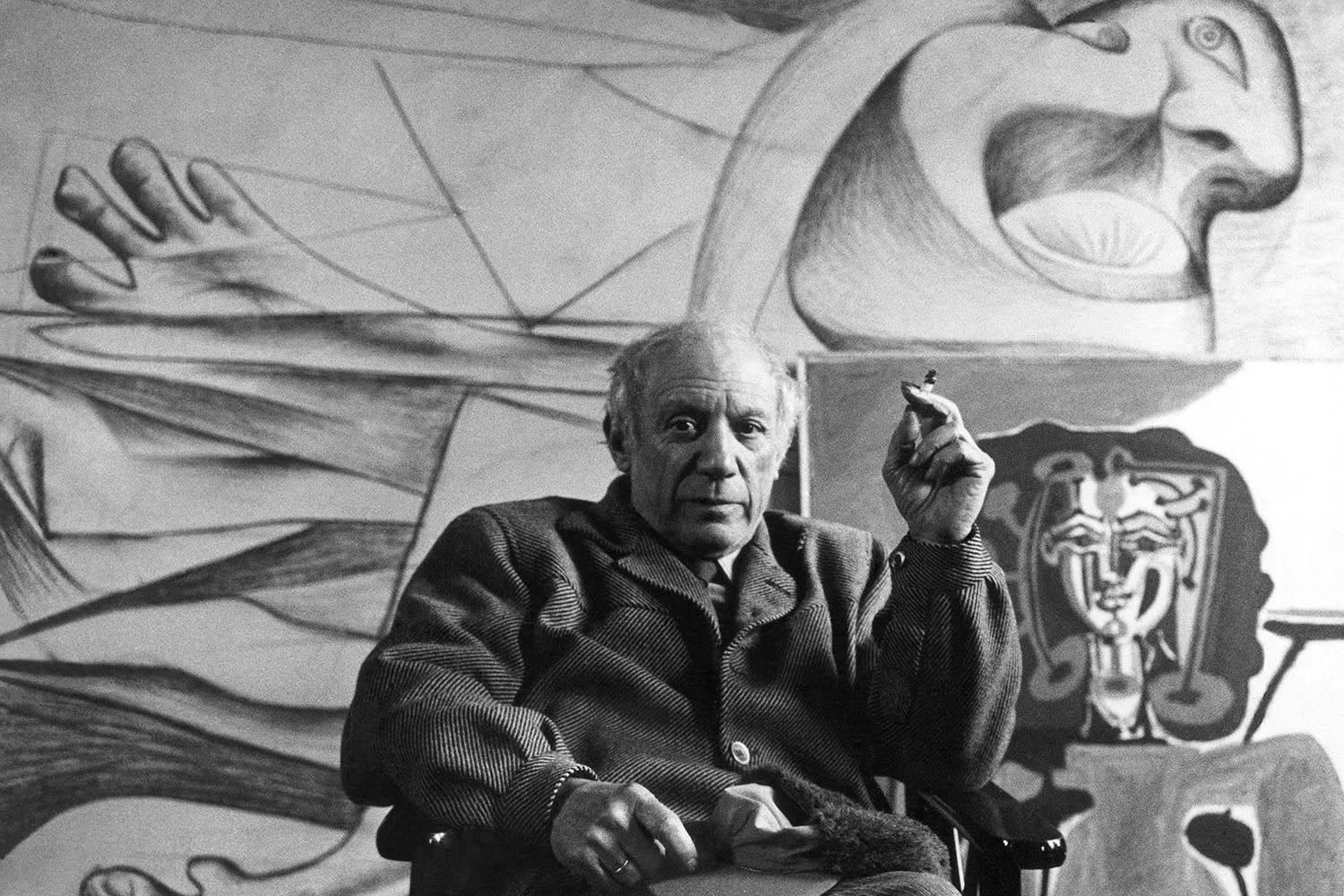

Lewis has fun with such cranks, but is less persuasive when dealing with artistic immortals. She complains that Giorgio Vasari, in his hagiography of Renaissance painters, hails Michelangelo as “il divino” and makes Leonardo da Vinci fit “another archetype of genius, the scatterbrained polymath”. But Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel is surely an almost cosmic spectacle, and Leonardo was more than a flustered ditz. She treats Picasso even more reductively. He appears here as a lucrative brand, requestioned posthumously to sell Apple computers and Citroën cars; he is also described – metaphorically, I hope – as a “cannibal” and “vampire”, which is what acquaintances called him when exasperated by his arrogance. About the visionary who painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Guernica, Lewis has nothing to say.

She notes that Shakespeare's admirers once called him 'Avonian Willy', which now sounds like an emasculating joke. Genius is phallocentric, but Lewis seems unimpressed by Shakespeare’s spurting “fountain of creativity”. She compliments him for enriching the language with a glossary of cliches, but then questions who actually wrote “all this great stuff”. So little is known about the man himself that Lewis can’t accuse him of self-puffery, spousal abuse or other domineering traits she castigates others for; she therefore suggests that maybe “Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare’s plays”, in which case the obscure fellow who “had geniusdom thrust upon him” is an impostor, a fraud, or perhaps a hack who has “ended up working for the Warwickshire tourist board”.

For Lewis, genius is ‘a rightwing concept, because it champions the individual over the collective’

For Lewis, genius is ‘a rightwing concept, because it champions the individual over the collective’

The most disreputable of Lewis’s subjects is Chris Goode, a theatre director who required the young men he recruited for his company to masturbate during auditions; in 2021, he killed himself when arrested after an archive of child abuse images was found on his computer. The sad and squalid tale is out of place here: Lewis admits that Goode was no “world-bestriding genius”, and although she likens him to Francis Bacon, who also “felt an erotic charge from male violence”, she places the comparison inside a parenthesis because she knows that she’s stretching a point.

Much more convincingly, Lewis concludes with a slangy takedown of Silicon Valley’s tech bros. In the case of Steve Jobs, “the assholeness was indivisible from the genius”, while Elon Musk has lapsed “from talented innovator to inveterate bloviator and shitposter”. Despite these cloacal slurs, Lewis is brilliantly perceptive about these men and the cults that form around them: she sees them as modern versions of the tribal shamans who “deviated from normal humanness”, claiming to possess a private line to the gods that gave them prophetic foreknowledge of the future.

Related articles:

Yet Lewis at last startlingly succumbs to the aspirational energy that mutant, semi-cybernetic geeks like Musk embody. On a trip to Florida she drives her SUV to the Kennedy Space Center and witnesses a rocket launch, which she calls “one of the most humbling sights that the modern world has to offer”. As the shaft punctures the sky, she is “swept up in the romance, the ambition, the sheer unlikeliness of it all”. Then why, I wonder, is she earlier so sceptical about Vasari’s exaltation of Michelangelo, or about the 1769 jubilee in Stratford that set up Shakespeare as a god with the actor David Garrick as his high priest? The genius myth may be a flattering fiction, but it reveals a truth about our earthbound species and its dazzling, almost supernatural achievements.

The Genius Myth: The Dangerous Allure of Rebels, Monsters and Rule-Breakers by Helen Lewis is published by Jonathan Cape (£22). Order from observershop.co.uk. Delivery charges may apply.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photograph courtesy of Getty