Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures

Caroline Walker: Mothering

Both at Hepworth Wakefield; until 27 October

Helen Chadwick was at the peak of her fame when she died, suddenly, in 1996 at the age of 42. The loss of such a superbly original mind remains incalculable to British art. Whatever killed her seems to have been the kind of stealthy virus that might have been the subject of one of her own works.

Tough, forensic, unflinching in her focus on sex and death, flesh and blood and the strangeness of the human mind, Chadwick was the metaphysical poet of contemporary art. She left not quite two decades of work, much of which can now be seen in all its extraordinary variety at the Hepworth Wakefield.

Here are stunning lightbox sculptures: three vast eyes, in Perspex, each iris formed out of wreaths of wild flowers, each pupil opening on to a glowing green chamber behind. What we see, and what we think: the link between them is so beautifully conveyed here, in this Marvellian vision of a green thought in a green shade. Above them, an upended oval of radiant buttercups has a vulval oyster at its centre. What we see, and what we desire.

Here is her 1974 Face Mask, exquisitely stitched from more than 40 pieces of fabric, including Lurex and sequined vinyl for the lips, and fur eyebrows. Chadwick was only 21 when she made and wore this self-concealing couture. One of her earliest works involved casting her own face in jelly and then inviting the public to eat it. Bodies, mainly her own, were a lifelong medium.

And consumption was a perpetual theme from the start. Chadwick’s now fabled degree show in 1976 featured an ensemble piece titled Domestic Sanitation, which combined live performance, installation and video. A digitised film is on show at the Hepworth. Four women, in exaggerated costumes of transparent vinyl and latex, hoover and scour the premises of what appears to be some sinister combination of beauty parlour and gynaecologist. A silken voiceover advertises “Because you’re worth it” type products.

One of her earliest works involved casting her own face in jelly and then inviting the public to eat it

One of her earliest works involved casting her own face in jelly and then inviting the public to eat it

But what is it worth, all this endless drudgery? Chadwick makes a vicious circle of labour, reproductive health, cleanliness, female beauty and money. And the Hepworth is also showing the horrifying yet delicate costumes she made for a performance titled Bargain Bed Bonanza.

These include a superbly made see-through bikini, with battery-operated lights in strategic positions and a ticking mattress, which she herself wore, coming slightly unstuffed, a matching pillow over her head. Rape Mattress, as it is called, now has additional overtones of Abu Ghraib.

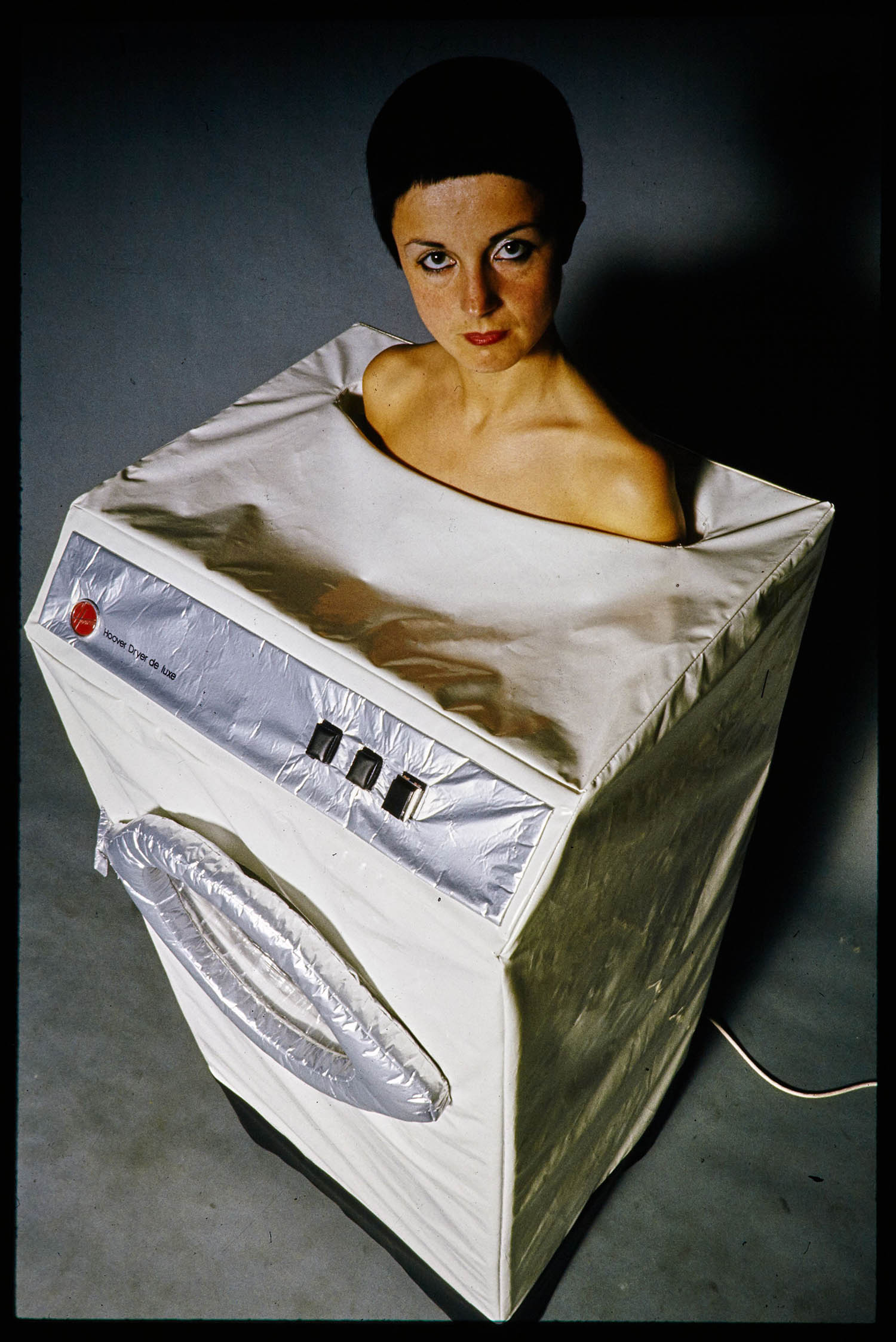

The elegance of these constructions is in exactly inverse ratio to the moral shock. Chadwick, so nimble, neat and orderly in many photographs through this show, had the most mordant intellect. Her seminal photographic series In the Kitchen fuses woman with white goods to the point that she has herself become a household appliance: laid out inside the open coffin of a fridge freezer, peering out from a hob, its circular plates two glowing breasts.

The Hepworth has all the classics. It opens with Chadwick’s notorious chocolate fountain, suggestively spurting in luxurious bubbles. A later gallery presents her famous meadow of white flowers, made by casting the space created by pee holes in the snows of Newfoundland in the 1990s, still fresh as a daisy. And the curators have given due space to that grand underwater ballet titled Of Mutability.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Using a colour photocopier, still novel in 1986, Chadwick created a blue sea teeming with white forms that spreads across the gallery floor. Rabbits, mermaids, goddesses, dancers, swans, flowers, heraldic creatures: it is a swimming fantasia of dream, myth and desire. And it is all created by the simple innovation of laying objects, and the artist’s own naked body, directly on the copying machine.

Chadwick’s influence on a generation of British artists is so tidal that associations come to mind, irresistibly, all through this show: with Sarah Lucas’s stitched and stuffed sculptures, with Marc Quinn’s blood head, with Anya Gallaccio’s slowly withering flowers. It is no surprise that Chadwick taught several YBAs. But still she remains so singular, and radical.

There is nothing to compare with the image-sculpture fusion of Ego Sum Geometria, for instance, made when Chadwick was 30. This tells the story of her life in wooden solids, each representing an actual object: a font, a pram, a vaulting horse, a cube (for her studio), an upright oblong (for her first front door). And over each, like shifting memories, are shadowy images of herself made with a photocopier in different sizes: tiny fingers on piano keys, a small self sleeping inside a pyramidal tent or trying, as it seems, to fit back inside that pram; a memoir, with all its yearnings, in three dimensions.

Chadwick’s preoccupation with women’s lives is paired, not incidentally, with a exhibition of paintings in the adjacent galleries by the Scottish-born artist Caroline Walker. A 20-week scan, a birthing ball, midwives circling a hospital bed, the half-light of a small hours feed: every familiar scene is made new through soft and painterly brushwork. Tellingly, Walker’s canvases are sometimes as large as an old master battle scene. But best of all is a small still life of infant bottles drying in a rack by twilight, humdrum reality made graceful and pale as a Morandi.