Related articles:

A flash of brilliant yellow feathers, from the wing of a bird in the Hawaiian hills, came to rest in London in the spring of 1812. Rare and precious, they were from an otherwise raven-black bird. Men with sap-baited poles lured honeycreepers from the sky, plucked their tufts and then released them back into the air. Weightless, bright, their plumage would become part of political history.

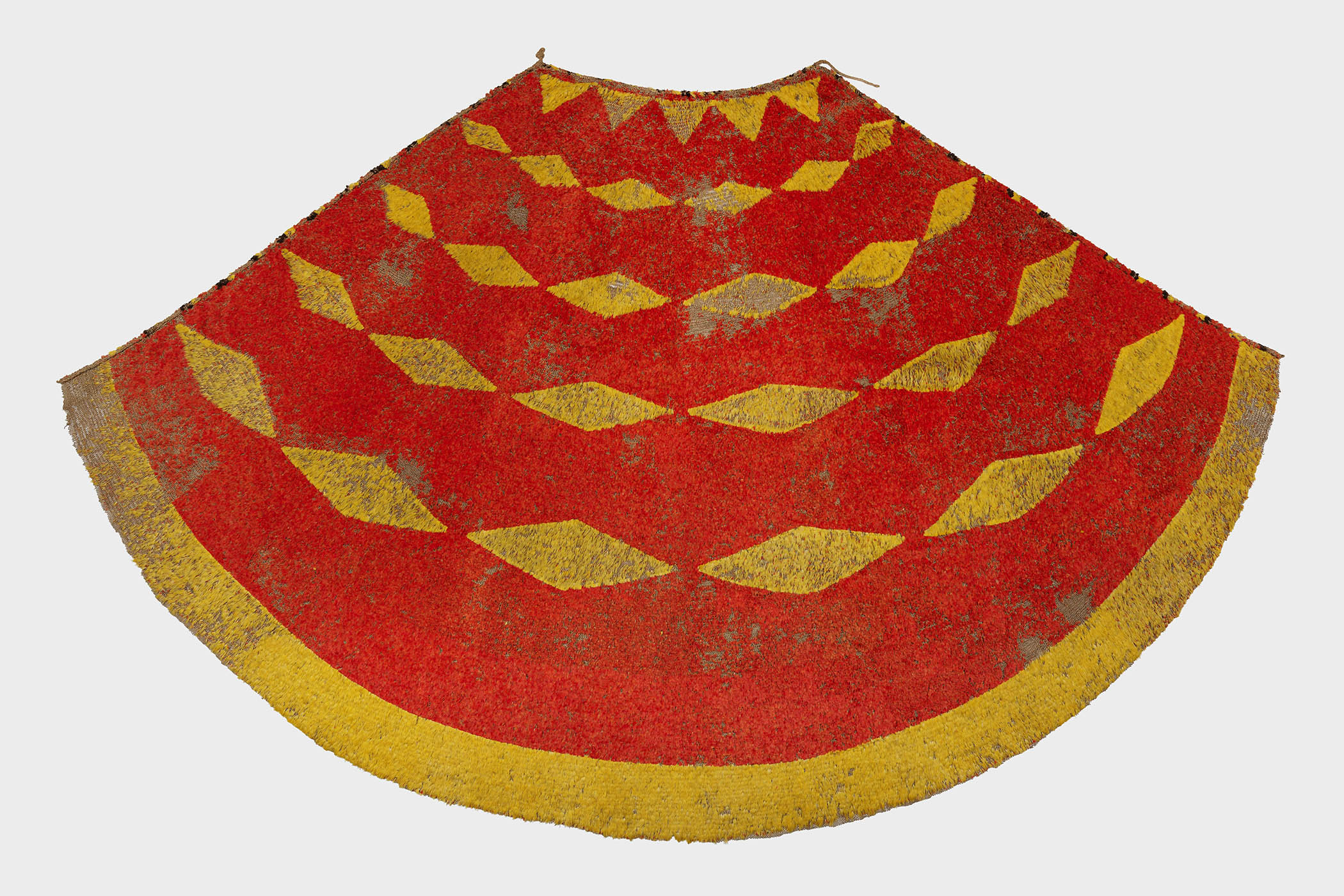

The king of Hawaii had a cloak made from these yellow feathers, radiant as a sunrise. It is said to have taken almost half a million of them. Weavers stitched them on to netting of plant fibre to create a garment as soft as swan’s down. There were other patterns too, involving scarlet and black feathers: diamonds, triangles, crescents, ribboning stripes. A magnificent diamond-patterned cloak, in all three colours, was commissioned by this king, Kamehameha I, for a leader more than 7ft tall.

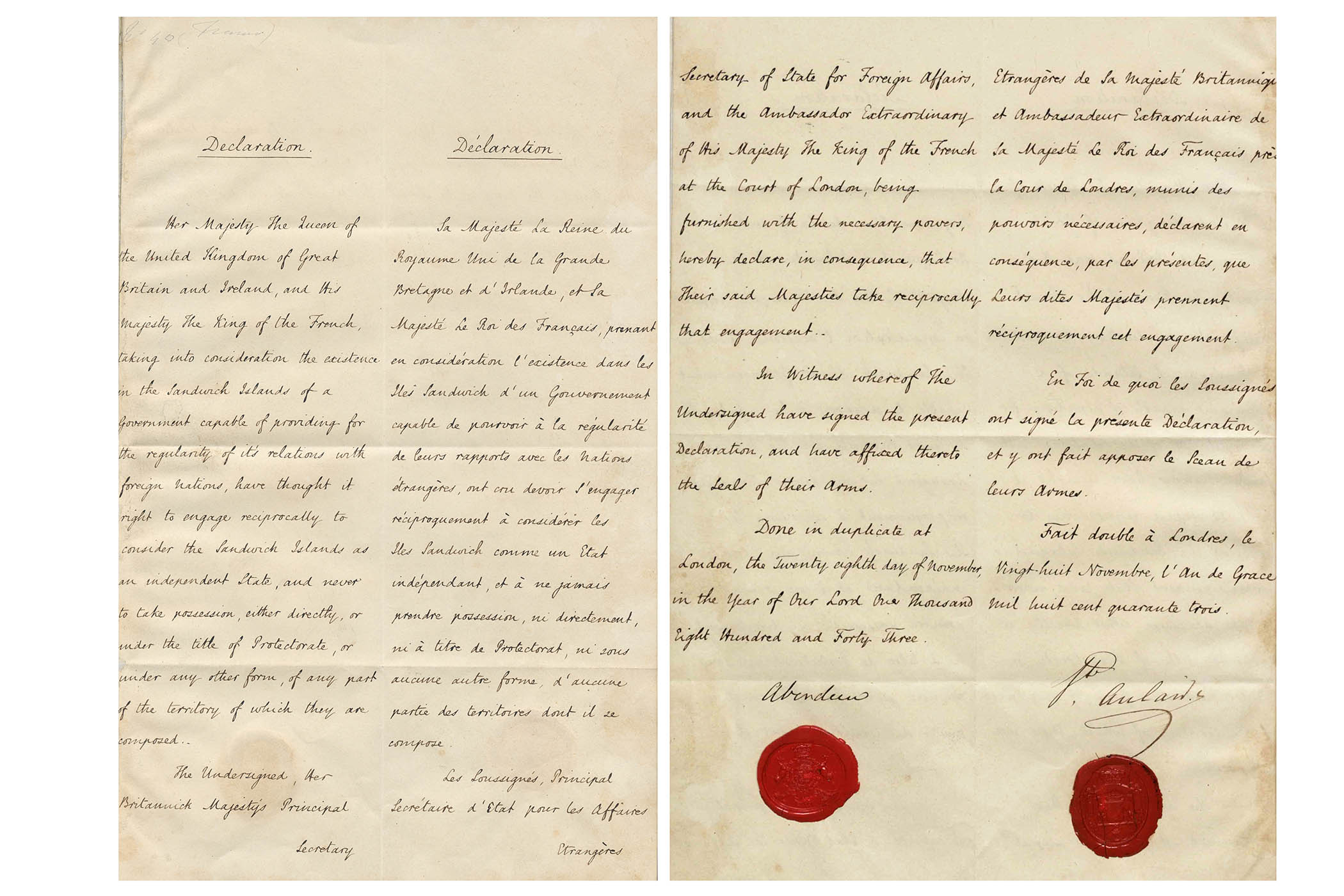

Whether this was pure fantasy, or generosity, will never be known, but its recipient was certainly much smaller. A gift for George III of England, the cloak was sent to London by Kamehameha in 1810 with a letter appealing for British protection against foreign powers. The voyage took a bewildering two years, by which time George III was so insane that the gift was received on his behalf by the Prince Regent, who had it displayed in Carlton House as a “Curious Feather Coat… Sent… by... King of the Sandwich Islands”. A letter was sent back to Hawaii with vague promises of support and a gold-laced cocked hat, which is roughly where those promises seem to have ended.

Years pass and both kings die, succeeded by their eldest sons. The young King Kamehameha II of Hawaii – henceforth Liholiho – begins to welcome Christian missionaries to the islands. The harbours are open. Some traditional temple images are destroyed. When George IV sends a schooner across the Pacific to Liholiho in 1822 for his ever-growing collection of sea-faring vessels, Liholiho writes to thank him with a new request for the unified Hawaiian archipelago to be placed under British protection. “The former idolatrous system,” he writes, “has been abolished in these islands, as we wish the Protestant religions of your Majesty’s dominions to be practised here.”

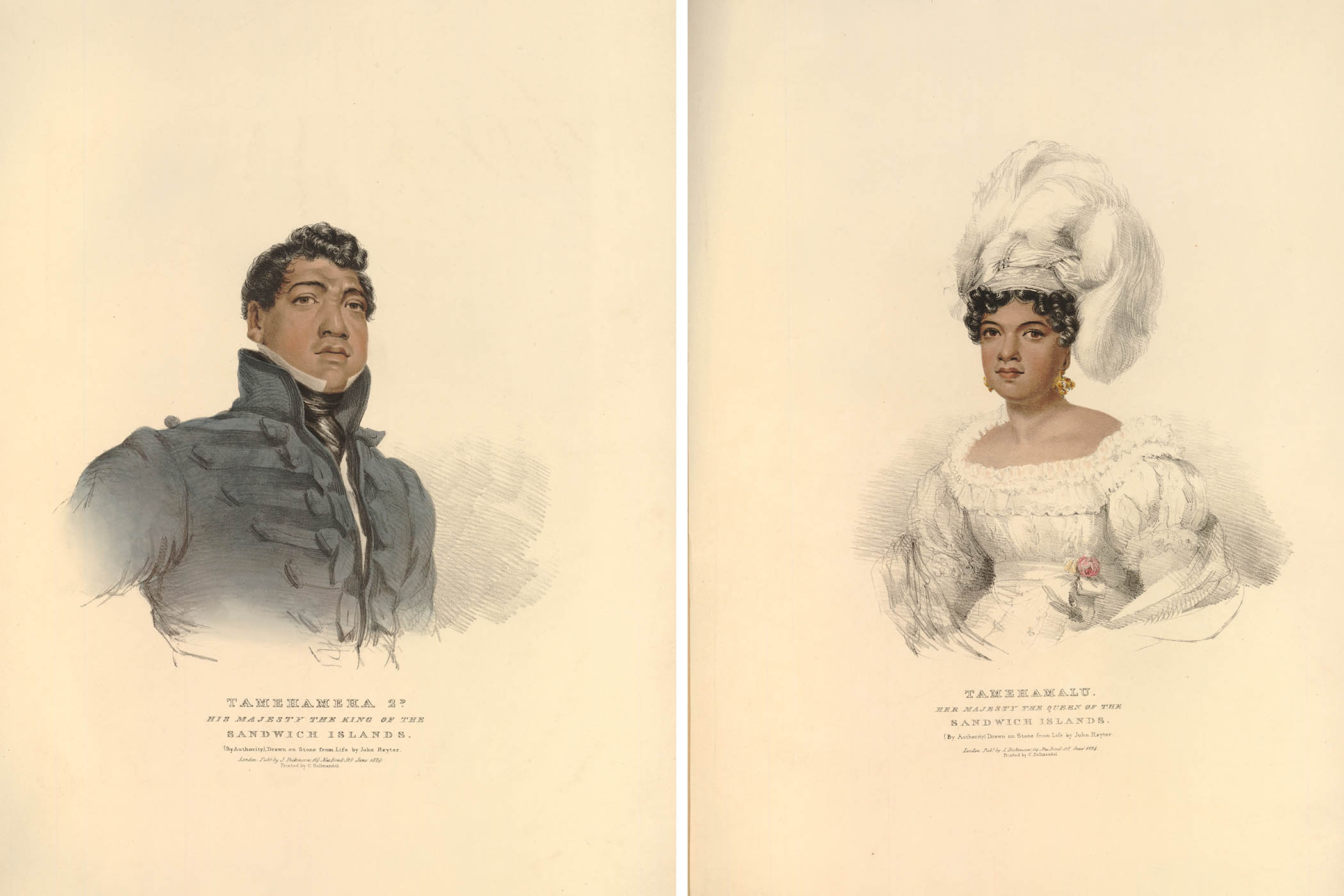

A ‘stupendous’ cloak is on show at the British Museum. Main image: King Liholiho (Kamehameha II) of Hawaii and Queen Kamāmalu

George IV’s ‘surprisingly puny’ coronation coat

Liholiho, having waited for a reply that never came, decides to set sail for London, where the cloak has long since disappeared into George IV’s massive costume collection. He will see other Hawaiian creations on display in the British Museum. He will visit the Royal Academy’s annual show at Somerset House, take in musicals in Covent Garden, cheer on the horses at Epsom. But he will never see the spectacular cloak his father sent to George III, nor will he ever meet George IV – the mad king followed by the bad king, as the old saying goes – because of the desperate tragedy that awaits him.

There are 12 people in the Hawaiian royal party, including the king and his young queen, Kamāmalu. They embark on a whaling ship called L’Aigle, captained by one Valentine Starbuck of Nantucket. It’s a carnivorous voyage, with several hundred live pigs, cows and chickens on board as future meals. More precious yellow feathers are given as royal gifts when the Hawaiians land in Rio de Janeiro, along with another magnificent cloak, alas now lost to the fire that destroyed the National Museum of Brazil in 2018.

One member of the royal party dies at sea. Another is left behind in Rio, possibly because of Starbuck’s plot to become the principal interpreter in England. He is a dubious figure in this story. The Times, announcing L’Aigle’s arrival, reports that the captain “has brought with him one of the idols formerly worshipped by the islanders. It is as large as life, curiously carved, and is intended by Captain Starbuck as a present for the British Museum.”

The idol in question is almost certainly the towering wooden god, only recently rediscovered, that will stand sentry outside the British Museum’s Hawaii show from 15 January onwards. How it came into the collection – or Starbuck’s hands, if indeed it did – remains a mystery.

Related articles:

After 153 days at sea, the ship docked in Portsmouth on 16 May 1824. A carriage rattled the king and queen through muddy downpours to London, where they took up rooms in Osborne’s hotel on John Street in the neoclassical Adelphi development lately designed by the Adam brothers. (The hotel is gone, but the elegance of several other buildings survives.) Here the royal party would remain for several weeks, constantly hoping and waiting to see George IV.

News of their arrival at Portsmouth appears in the press the very next morning. The Times churlishly reports that they must be here to study British laws and appeal for British protection, both of which “might equally have been achieved had their Majesties stayed in their own dominions”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Other papers become fascinated by their appearance. “A person who visited them yesterday found their Majesties amusing themselves with a game at whist, the Queen having for her partner her female attendant… The ladies were dressed in loose robes de chambre, of straw colour, tied with rose-coloured strings, and on their heads they wore turbans of feathers of scarlet, blue and yellow.

The two men appeared in plain black coats, silk stockings, and shoes. These islanders are of a very large size. The men appear to be above six feet… the females… proportionably taller.” The party go to Westminster Abbey, to Fulham by boat, to witness a balloon flight in Islington.

An appointment with George IV is at last scheduled to take place on 21 June. But by then it will be too late

An appointment with George IV is at last scheduled to take place on 21 June. But by then it will be too late

Tailors arrive with more clothes. Crowds begin to gather outside the hotel. The owner applies to the local magistrate’s office for protection against “the crowds of idlers who throng the front of his house from morning to night, for the sake of getting a peep at their Sandwichean Majesties… No coach could approach the door of the hotel but it was instantly surrounded on all sides by a rabble of the open-mouthed curious, in search of copper-coloured Royalty.”

Vicious cartoons appear. One depicts King George having his way with Queen Kamāmalu. Another shows the Hawaiians in feather skirts and body paint, presenting a pair of feather breeches to Frederick “Poodle” Byng, a Regency dandy sent to escort them round town. He is hatching the idea of his own feather factory.

Byng had been sent by the foreign secretary and future prime Minister George Canning. For all the satirical jibes in the press, the official tone was beginning to change. Perhaps there is something in it for the British, after all, protecting these prosperous islands from marauding Spaniards, Russians and Americans.

Canning throws a grand reception for 200 guests at his Kensington house on 28 May, inviting several dukes to meet the Hawaiians. He is said to have whispered to Wellington that Kamāmalu was so graceful she would have been “the life and ornament” of London society had she only been a British queen. An appointment with George IV is at last scheduled to take place on 21 June. But by then it will be too late.

A feathered Hawaiian headdress

A letter from Liholiho’s father, Kamehameha I, to George III, appealing for British protection against foreign powers. It took two years to arrive

George IV, then 61, was already one of the worst monarchs in British history. He had blown a fortune on Brighton pavilion, commissioned ludicrously expensive clothes while the nation struggled with poverty, and humiliated his wife, Caroline of Brunswick, by attempting to change the law in order to divorce her, even excluding her from his coronation.

He was massively obese, addicted to laudanum and so despised by the public that when he died in 1830, the Times wrote: “There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow-creatures than this deceased king.”

George obviously refused to drag himself away from the groaning table to welcome Liholiho and his wife – or so I imagine. But Alice Christophe, curator of the British Museum exhibition, tells me that nobody knew the Hawaiians were coming. Liholiho’s letter applying for a royal audience only reached London after he had arrived at Osborne’s hotel.

We are following the Hawaiians’ footsteps through central London. Here is the corner of John Adam Street, where the carriage waited to take them to Whitehall, to Hyde Park, to Westminster Abbey. Four blocks down the Strand is the Royal Academy exhibition, this year starring Landseer and Constable. On 4 June, Liholiho and his wife cross the Strand to the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, where the manager shows us the royal box reserved for them by George IV.

A contemporary lithograph shows the Hawaiians jammed in together: the king beaming at the stage next to his queen in pink, garlanded with roses. They are, it is said, watching Rob Roy MacGregor, adapted from Walter Scott’s novel with lyrics by John Davy, which is fitting, since the theatre is now owned by Andrew Lloyd Webber.

The Hawaiian royals were clearly the spectacle that night, there to see and be seen. (Legend has it that George III once had an identical box installed on the other side of the stage for George IV, father and son were so opposed; perhaps history repeats itself.)

The Hawaiians continue to wait and wait to meet the king. At the British Museum they see exactly what we will see in the forthcoming show: gods and idols, bark cloth that shimmers like watered silk, feathered figures and visions.

One tremendous installation brings many together, like a living crowd: feathered headdresses shaped like the helmets of Roman centurions, feathered necklaces and headbands, feathered standards that seem to explode like fireworks; above all, a sequence of stupendous feather cloaks.

One is patterned with yellow circles pierced with red dots, and gold bands pierced with double diamonds. Associated with Captain Cook’s final voyage to Hawaii in 1778, it was displayed at the British Museum as early as 1803 and seems to be the model for the Hawaiian coat of arms.

Another, with its descending panel of black and yellow chevrons against red, was surely created in response to the European military uniforms seen in Honolulu from the 18th century onwards. But its blazing op-art is far more radical.

Still waiting to meet George IV, Liholiho and Kamāmalu have their portraits made in Regency style. He is upright in a wasp-waisted jacket, hair brushed upwards; she wears white satin and lace. They visit Chelsea hospital and the Royal Military Asylum for the orphaned offspring of soldiers. It is here that the party might have contracted measles.

The queen became gravely ill, with no form of immunity, and died at Osborne’s hotel on 8 July. She was 22 years old. The king was moved to the Caledonian hotel, its premises still there on Robert Street by the Thames. It was hoped that the view of the Thames through its high windows might help, if not the seven royal doctors in attendance. But Liholiho died on 14 July, aged 26.

The room was hung with feather cloaks. Prayers were said. Crowds gathered in mourning outside. Liholiho’s body was embalmed and borne on a bier to the crypt of St Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square, where it lay alongside that of the queen until a ship was made ready to carry them home across the seas. They lie together still, in the Royal Mausoleum in Hawaii.

George IV at least paid the hotel bills and commissioned the ship. But his carelessness, and the casual racism of Regency London, gawping at these “curiosities”, is dramatically exposed in a climactic moment in this show.

Rounding a corner, you are confronted by the opposition of two cloaks. One is the original Hawaiian gift sent to George III, the other is George IV’s coronation coat. The contrast is shocking. George IV’s outfit is silk, velvet and fading bling. Slope-shouldered, it is surprisingly puny. You see him wearing it beneath about half a mile of ermine in Thomas Lawrence’s c famous oronation portrait. George had not yet acquired the girth – he is said to have been more than 127kg (20st) in later life – that made him seem so vast, but his clothes seem both cheap and small.

The Hawaiian cloak, on the other hand, appears superhuman in length. A soaring creation of scarlet, yellow and black, its hundreds of thousands – possibly millions – of feathers are each exquisitely tethered, with threads, to a fine fibre mesh. It is far more beautiful than brass buttons and gilt froggings, and its pure bright yellow is undiminished.

Towards the end of this show lies an open book. On one side is a tuft of brilliant yellow feathers. On the other is a 19th-century watercolour of the mamo bird, otherwise black as night, from which such feathers were taken. They glow, undimmed by time, or light, or politics, all the way through this show. As for the mamo itself, like all the dead kings of Hawaii, the bird is now extinct.

Hawai‘i: A Kingdom Crossing Oceans is at the British Museum, London, from 15 January to 25 May

Photographs by © The Trustees of the British Museum; Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd 2025/ © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 © Royal Collection Trust