Ken Caillat has a lot to thank his notes for. Before he was called up to be the sound engineer for Fleetwood Mac’s album Rumours in 1976, Caillat spent five years as an intern jotting down what the great engineers in front of him were doing as they recorded the music of artists like T Rex, Paul McCartney, Joni Mitchell and Crosby, Stills and Nash.

Twelve days before Caillat travelled to Sausalito, California, to start recording Rumours, he had no idea who Fleetwood Mac were, but, thanks to his notes, he felt prepared. “I had a whole thick manuscript of tricks,” he says. “So when I was ready to go, I unleashed them.”

This unleashing took place over the turbulent 12 months during which Fleetwood Mac recorded what would become one of the biggest-selling albums in history, with Caillat’s sizable contribution resulting in him being credited as a co-producer.

Again, he made notes, a detailed record of every day of that year – the band’s guitarist Lindsey Buckingham walking into the studio rubbing his hands, which was a sign that it would be a good day; the temperature on the August afternoon they tried to trim down the song Silver Springs; keyboard player Christine McVie’s April Fools’ Day prank in which she told her attorney that the band were refusing to finish the album – these details form the basis of Caillat’s 2012 book Making Rumours: The Inside Story of the Classic Fleetwood Mac Album, which he co-authored with Steven Stiefel. And it was because of the exactitude of Caillat’s notes that, when he sat down to watch the musical Stereophonic on Broadway in New York last year, it felt uncannily familiar.

“I can tell you what I told a friend last night,” says Caillat, speaking on a video call from behind the console of his recording studio in Westlake, California. “My book is pretty much about me and my co-producer sitting at a console like this, looking through a glass window on to the studio. When I went to see the play, that’s exactly what it was.”

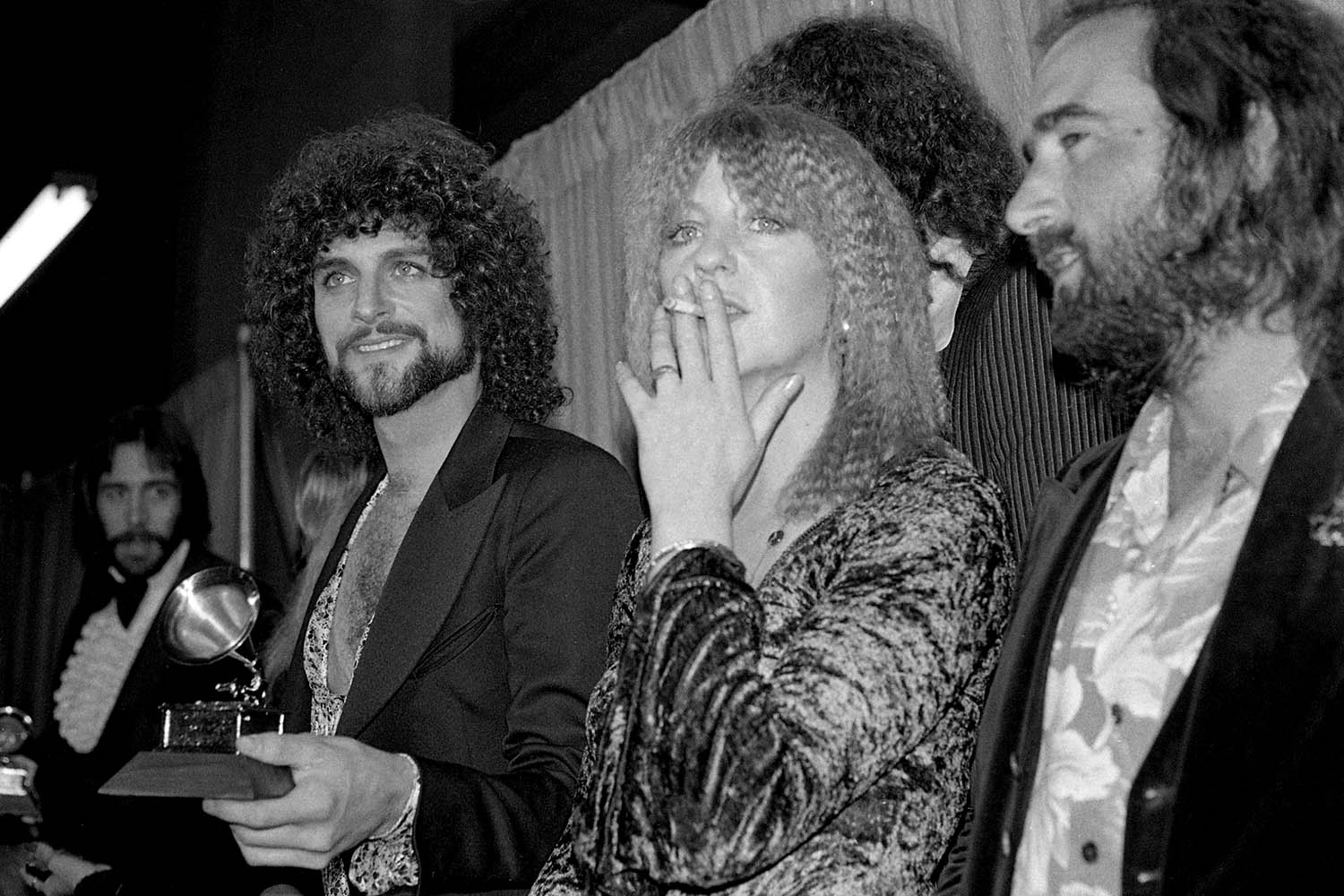

Lindsey Buckingham, Christine McVie and John McVie at the 1978 Grammy awards, at which Rumours won album of the year

Stereophonic opened in 2023 and transferred to Broadway last year, later receiving a record 13 Tony award nominations. In June it moved to the West End in London to rave reviews, recently extending its run until November due to demand. You won’t find mention of Fleetwood Mac during the play, in its programme or marketing material, but the fingerprints of Caillat’s book are all over the story.

As in Making Rumours, which begins with a chapter entitled Ken’s Wild Ride, Stereophonic is told from the perspective of a newbie sound engineer called Grover and his co-engineer. It places the audience right at the console with him as he frets over relentless late nights and the musicians’ mercurial temperaments. In terms of nationalities, relationships and genders, the composition of the band exactly matches that of Fleetwood Mac’s mid-1970s lineup, and the play takes place in the same time period and location in which they made Rumours.

In his book, Caillat walks us through the making of each track, embroidering the mechanics of production with dramatic behind-the-scenes stories. After two takes of Oh, Daddy, Caillat says that Christine McVie asked him which was better, but neither he nor fellow producer Richard Dashut wanted to answer her.

Related articles:

“We don’t want to have to come in and listen every time we try out something different,” Christine said firmly. “We want you guys to start paying attention to tempos and keys and tuning, and other important things, and help us out here.”

Later, while recording Second Hand News, Caillat recalls that Buckingham insisted on taping over a take of a complex guitar solo to make space for him to try it again. When he realised that the previous attempt was really gone, he called Caillat an idiot and throttled him.

Both of these incidents occur almost identically in Stereophonic, which has the same structure of guiding the audience through the making of an album and showing the blood, sweat and tears that went into nailing a particular piano chord or drum beat.

Ken Caillat, left, and Richard Dashut worked with Fleetwood Mac on their albums Rumours, Tusk and Mirage

Other striking similarities stack up as the play progresses. Grover’s catchphrase, “wheels up”, is what Caillat used to say when they commenced recording because there were commercial airline pilot seats in the control room. There’s a strange rant about the Sausalito houseboat wars that Caillat remembers hearing from a drunken John McVie; this also occurs in the play. Making Rumours also recalls that one evening the singer Tony Orlando came into an Italian restaurant in Los Angeles where the band frequently ate; in Stereophonic, one character says that she “had mai tais with Tony Orlando last night”.

These, and more repeated specifics that go well beyond mere coincidence, were detailed in a lawsuit that Caillat and Stiefel brought against Stereophonic last October. Two months later the production and its writer, David Adjmi, had settled the dispute confidentially. When approached for comment by The Observer, the production confirmed the case had been resolved but declined to comment on the terms of the agreement. The settlement comes after Adjmi was accused of copyright infringement in 2015 when the copyright holders of the sitcom Three’s Company sued his play 3C. In that instance, he won the case because his story, a parody, was found to constitute fair use.

“When I saw Stereophonic, I was a little upset that they didn’t come and ask me for it,” says Caillat. “But I can say that they did a fairly good job of mimicking what I said. I can’t really talk about it too much. If they were here, they’d probably be choking me right now, but you only live once.”

Naturally, after seeing the play, Caillat had some notes. In one scene, Grover pushes the drummer into using a click track because he can’t stay in time. “We don’t use click tracks in that manner,” he says. “You don’t arbitrarily say, ‘I’m going to turn it faster.’ He would have been fired if he was doing it like that.”

Another fabrication is the romantic interest between Grover and the keyboard player and vocalist Holly, who appears to be a stand-in for Christine McVie. “I didn’t have any affairs with the girls,” says Caillat. “I was so starstruck I thought, well, way out of my league.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The book opens with the line, “You never know when you’re going to be part of history”, and throughout there’s a sense of Caillat’s perspective, something he would have liked the play to explore in more detail. “I thought [Grover] was underwhelming as an engineer,” he says. “He didn’t talk much about, ‘let’s make this guitar sparkle more’, so that people don’t know how to make the record really, unless you read the book.”

Despite these grumbles, Caillat found it emotional to sit and watch the story after so many years. “I’m proud of the play, you know? I’m proud of the book, and it’s close enough for me. I tried to get the play to sell my book, [so there is] at least some sort of connection. They didn’t want to do that, but I can always stand outside the theatre and sell it myself,” he jokes.

In the lawsuit, Caillat and Stiefel claimed that Stereophonic had a direct effect on the opportunity to turn Making Rumours into a film given that Adjmi had spoken publicly about his intention to do the same with Stereophonic. Now, with the renewed attention that the play has brought to the story, Caillat is being approached about a possible film. “Yesterday I got a call from a big director. He wants to come here next week and talk to me about making the book into a movie,” he says, adding that it was being pitched as an Almost Famous narrative. “While we were recording, the people who worked at the studio used to whisper, ‘That Caillat, he’s such a lucky bloke!’”

The possible adaptation comes as Fleetwood Mac have authorised an Apple documentary about the band from director Frank Marshall, which will span the band’s 50-plus-year history and include previously unseen footage. “Fleetwood Mac somehow managed to merge their often chaotic and almost operatic personal lives into their own tale in real-time, which then became legend,” Marshall said when the documentary was announced in November last year. “This will be a film about the music and the people who created it.”

It will also offer the chance for the band to set the record straight on those tumultuous years, as the documentary includes new interviews with band members, as well as archival conversations with the late Christine McVie.

Caillat hasn’t had contact with the band since publishing his book, but he believes at least one of them wasn’t happy about it. “Lindsey didn’t like the book, and he told the band not to support it,” he said. “I think there was a sense that what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, but I looked at it like: hey, I waited 40 years! There’s a lot of stuff I didn’t tell. I thought it was more important to get the story out because it’s a great story.”

Stevie Nicks performing with Fleetwood Mac in 1976

When contacted, the band’s representatives confirmed they had issued no statement on Stereophonic and declined to do so, but Caillat says he’s heard about one reaction. “Mick [Fleetwood] thought he should be able to get a royalty from it, but his attorney said, ‘You can’t get a royalty from history’, or something like that.”

Caillat didn’t anticipate the success of Rumours, but, at the time, he could see that the band were giving their all. “They said to each other: we know we’re going to break up, but let’s make this record anyway,” he said. “They put everything into that music.”

The band’s legacy includes the delayed success of Silver Springs, which never made it on to the album. In Making Rumours, Caillat explains why: it was too long, and the band felt that without it, the album flowed better.

But in recent years Silver Springs has become an unlikely TikTok sensation, with young newcomers to Fleetwood Mac making fan edits of Stevie Nicks singing, “You’ll never get away from the sound of the woman that loved you”, while staring down her former lover Buckingham on stage. Stereophonic leans into the interband drama, with Buckingham’s supposed stand-in character Peter pressuring the Nicks-like character Diana to cut down her song, Bright, because he was threatened by her talent.

As with much of Stereophonic, it favours scandalous theatrics over the more nuanced, complex reality. Still, the heartache of Silver Springs was real for Nicks, who had dedicated the song to her mother, and was informed by Fleetwood in the car park of the recording studio that the band had decided without her to take it off the album.

Investing in a piece of that history, in 2020, Caillat clubbed together with a few investors to buy Record Plant, the rundown Sausalito studio where the album was recorded, and bring it back to life. “It’s taken us years to get the mould and rats out and rewire the place,” he said. “But it’s still as magical as ever to be where Dreams was written and recorded.”

His notes were important, but Caillat says the memories are vivid enough that they come hurtling back. “I still remember everything about it, every guitar lick and little thing that we decided to leave in that was maybe a mistake but turned out to be brilliant,” he says.

And while he is still publicly left out of the story of Stereophonic, he jokes about a way they could make amends, saying: “Maybe I should get one of the Tonys?”

Photographs by Marc Brenner, Herbie Worthington, Getty Images