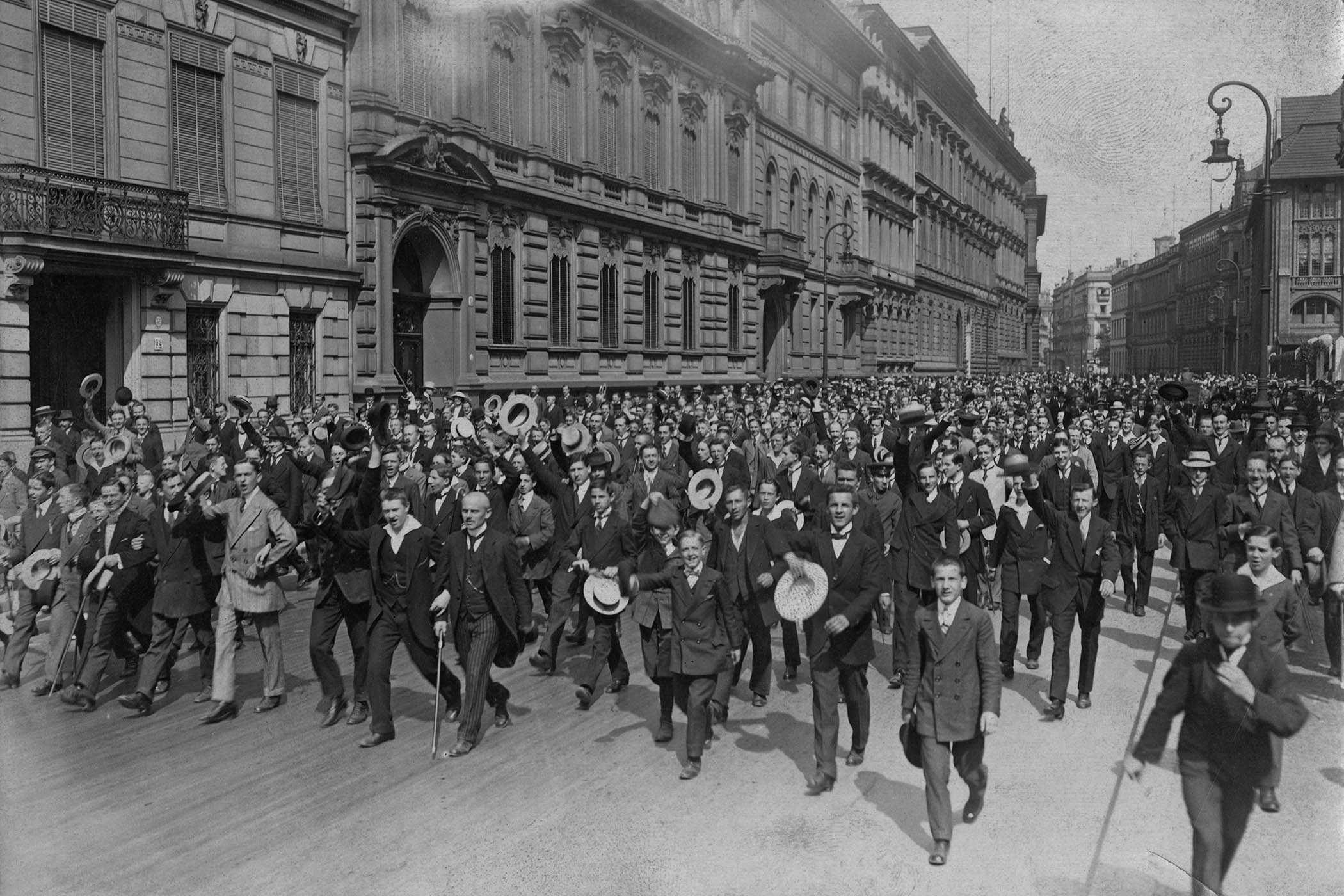

This article was originally published on 26 July 1914 under the headline ‘European peace in danger’. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia two days later

Experienced critics of foreign affairs have long been convinced that the Great War, if it ever came at all, would come with utter unexpectedness. Suddenly in the Near East a cloud that seemed no bigger than a man’s hand threatens the blackness of tempest that overwhelms nations.

The peace of Europe, menaced above all by Servian passion and conspiracy, may yet be saved at the last hour by the submission of Belgrade, or may be wrecked by Servian contumacy.

No wise man can approve wholly the unmitigated violence of the Hapsburg ultimatum and the tremendous hazards of its indirect challenge to Russia. Yet we hope that the public opinion of this country will be very slow to condemn altogether the harsh determination of Austro-Hungarian policy. It is extreme. It is dangerous. It sets the whole fabric of Europe in peril. It runs within a hair’s-breadth of precipitating a world-war. It aims deliberately at inflicting an unexampled humiliation in punishment for one of the basest and most cruel political crimes that have stained the reputation of a race. We cannot defend in theory a procedure on the part of Vienna which seems designed to make a peaceful accommodation impossible and to open a sure path to military vengeance swift and overwhelming. On the other hand, it is quite doubtful in all the circumstances whether any much less bitter and peremptory method would have had any fair chance of securing a proper result.

***

We recognise that Russia cannot tolerate the destruction of Servia and is bound to stipulate as to the limits of Austrian intentions. But let no one, on the other hand, lift a finger or raise a voice to encourage Servia in obstinacy or even to save her from the due measure of immediate punishment which the passions and follies of her extremists have deserved, and the negligent presumption of her statesmanship has courted.

The psychology of Serb megalomania has been inflamed to a most mischievous degree since the successes of King Peter’s subjects after the recent Balkan wars. These achievements were partly due to skill and bravery, but largely to the efforts of others and to an astonishing good fortune. Since then Serb aspiration and ambition have been heated to a mad temperature. At the same time, the seizure of the Bulgarian portions of Macedonia and the subsequent persecution of the Bulgarian churches and schools have made ridiculous the claim to Bosnia on purely racial grounds.

Belgrade has been a hotbed of dreams and plots against the very existence of the Hapsburg Monarchy; therefore against the conditions which are indispensable to the equilibrium of Europe and the maintenance of its peace. Of this moral atmosphere the double assassination at Serajevo was the direct result. Considering all the circumstances, the whole state of things which led to these infamous murders ought to be condemned and repressed with uncompromising sternness by every principal Government in Europe, and, above all, by that of the Tsar.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo on June 28 1914, five minutes before they were assassinated by Gavrilo Princip. Photo by Bettmann

Let no man think for a moment that the evil consequences of such crimes, due to unbridled agitation and desperate fantasy, can be confined to any one country. The Servian Ministry and people were not responsible for the murders. The agitation they indulged and covertly encouraged was responsible. There has been at Belgrade in the last few weeks no sufficient activity either of the moral sense or of practical judgment. In no adequate degree was there either reprobation or reparation. Servia had a month to ponder the matter and Servia, of herself, did nothing.

****

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Meanwhile any student of European politics must have marked that the tone of Austro- Hungarian warnings was ominously smooth. The problem was sternly studied from the political point of view. Every military preparation was quietly made. Then an irrevocable ultimatum in the most ruthless form conceivable came like a thunderclap. Forty-eight hours, ending at six o’clock yesterday, were allowed for the acceptance of demands which would mean the moral annihilation of the Servian State, followed by its relapse into political anarchy.

The ultimatum may be enforced even at the hazard of Russian intervention and a European war. Such a struggle would involve both France and England in moral difficulties of a very painful kind. They cannot desire to take part in the hugest conflict the world has ever seen in order to defend and encourage an aggressive and subversive agitation which seeks to shatter the integrity of Austria-Hungary and to overthrow the existing European system by destroying an element of balance which nothing thinkable could replace.

***

That can be no part of the policy of the Triple Entente.Though the name of Russia has been unwarrantably used in support of such plans, we refuse to think them part of the policy of the Tsar’s Government, sane and measured as it has been in recent years and adverse to all schemes of violence and adventure. No journal is more loyal than we are to the Triple Entente. But that combination exists for large and just purposes indispensable to the equilibrium and stability of Europe. The Triple Entente must not be made either the tool – or even the shield in the sequel to such episodes as the Serajevo murders – and of agitation which attempts to combine pure idealism in Bosnia with rank cynicism in Macedonia, and could not succeed without general overturn. It is high time that the extremists in Servia were brought to their senses. Belgrade, which has not fully accepted the strongest possible ultimatum, would assuredly have fenced more with a weak one. Then whatever the eventual compromise, the requisite moral impression could never have been created upon the pan-Serb agitators.

***

Infatuated and insolent as has been the pan-Serb agitation against the integrity of the Hapsburg monarchy, vile as was the murder of the Archduke and his hapless wife, the humiliation aimed at Servia is unexampled. In reparation for the crime "hatched in Belgrade," humble apology must be published on the front page of the Servian Government journal, and issued as an order of the day to the Army. The ultimatum names officers and officials to be dismissed. Above all, Austro-Hungarian agents are to be allowed to supervise the work of rooting out, as far as possible, the whole agitation which aims at the disruption of the Dual Monarchy in order to create, by the seizure of its present Serb and Croat provinces, a Greater Servia of some ten million souls.

Some of the conditions in the ultimatum may well seem brutal, excessive, and calculated to defeat their own purpose in the end, perhaps to increase in the long run the very dangers against which they are directed. On the other hand, Servian temperament in its recent exalted mood has been very difficult to deal with, and it is quite doubtful, as we have said, whether any feebler procedure would have been effective.

The moral point to remember is that in this business Austria-Hungary is fundamentally justified and Servia is fundamentally wrong. For no light reason has the old Emperor sanctioned a step attended by the imminent risk of a European conflict. A more timid and uncertain policy would have meant either, at no very distant date, the same risk of war, in perhaps more adverse circumstances — with constant unrest and apprehension in the meantime — or increasing pessimism throughout the Dual Monarchy, the fading of Hapsburg prestige, the decay of all security on the Southern frontier, the slow subsidence of foundations, and eventual collapse to the peril, as we think, of the whole existing structure of old-world States. By a merely passive policy in these matters Austria- Hungary cannot exist. The Ballplatz must be cautious. But from time to time it is driven by hard necessity to act, and when it acts it must act boldly.

*****

That is the moral point, but the practical point raises quite opposite considerations. There is no doubt whatever that Austro-Hungarian policy in calculating this blow had to make up its mind to hit hard. But the immediate force of the stroke after falling full on Servia carries beyond the mark and touches Russia.

At the meeting of the Russian Cabinet yesterday the ultimatum was unanimously regarded as an "indirect challenge," and with the approval of the Tsar a decision was taken to mobilise at once five Army Corps. Nothing else could be expected. If Austria-Hungary had a large moral balance to her credit as a result of Servian conspiracy and the recent assassinations, it will be well understood, by this time even at Vienna, that the Ballplatz has not only taken out by a single cheque, as it were, its whole fund of justification, but has over-drawn the bank.

European peace could never bear a repetition of the experiment, which may be disastrous even now. Yet, let us still remember the grossness of the provocation and the absolute necessity of calling Servia to order.

Again and again we have defended Servia in the past against the system of political pin-pricks and economic strangulation which had been employed against her. Against any wanton renewal of such a policy we would protest as firmly. But Servia on her side would do well for the next decade to consolidate, if she can, her very large and even excessive gains from the second Balkan struggle, and to recognise once for all that she must either face Austro-Hungarian hostility pushed in the end to war, or must honestly suppress a Chauvinistic agitation which avowedly seeks to sap and undermine part of her great neighbour’s political foundations. Otherwise a lesser Servia will be just as probable a result as a greater Servia.

****

Again, though we cannot be surprised by the support which Germany and Italy, for different reasons, extend in this emergency to the action of their ally, it must not be forgotten for a moment in any capital that the Triple Entente, morally embarrassed by the particular question now at hazard, must stand together with the whole of its power if other and larger issues should gradually be raised. Then, indeed, Austria-Hungary, with every opportunity to put herself in the right, might prove to have put herself disastrously in the wrong by the suddenness and violence of a stroke which, as we have said, amounts to an indirect, but extreme, challenge to Russia at the risk of the world's peace. We may best sum up our comment upon the procedure against Serbia by saying that if you could be entitled to burn down the house of a man who was himself an incendiary you would not be justified in setting fire to the whole street.

At the moment of writing the Government of M. Pasitch — which lives in dread of its unruly officers — has evaded the ultimatum, as was fully expected; Vienna has refused the request of Russia for an extension of time; the Austro-Hungarian Minister has left Belgrade. If Austrian troops now cross the frontier of Servia supreme efforts will still have to be made to quench the flames before they envelop a continent.

The duty of this country, in the first place, whatever it may be in the end, is to mediate, mediate, mediate. We must aid Russia on the one hand to secure guarantees against the annihilation of independent Servia without seeking, on the other hand, to save that culpable State from sufficient and memorable punishment. Sir Edward Grey, in his long and eventful term at the Foreign Office, has never had a more anxious task. His course will be adopted with due regard to all the vast interests at stake, and, despite the unmatched gravity of our own domestic crisis, the foreign policy of the King’s Government must be supported by the whole nation as one.

Latest Observer views: