Between 1980 and the mid-2000s China increased its exports dramatically. This year, its trade surplus passed $1tn.

For most of us the China shock – the surge in US imports of Chinese goods – was good news. It meant things got cheaper. The developed world is typically about £1,000 per household better off as a result. Lower inflationary pressure also allowed lower interest rates, encouraging investment in the economies of developed countries.

At the same time, the proportion of people in China living in extreme poverty fell from almost everyone in 1980 to almost no one today. These really were good times, and the world needs more big economic shocks like this.

Thankfully the next one may be upon us. This year, India will outpace China on growth for the fourth year running – something that hasn’t happened since at least 1960. Although it’s worth being a little sceptical about reported growth rates (the Chinese example should not be followed there), India is now 30% richer than it was before Covid and is growing at a pretty stonking 6% a year.

Indian inflation has collapsed – it is now close to 0%, down from about 5% a year ago. The Indian central bank cut interest rates from 5.5% to 5.25% this month, surely the first cut of many. Lower interest rates will spur investment and growth, and will probably make the rupee more competitive in international markets, encouraging exports further.

In the past decade or so India has made two significant moves: developing a pro-manufacturing industrial policy under the slogan “Make in India”, and deregulating the economy. Although “Make in India” has led to some successes – for example, getting Kia to build a full-scale car plant in Andhra Pradesh – it has not achieved much in aggregate. For example, the plan was to double the proportion of people who work in manufacturing to (almost) reach Chinese levels. That has not happened – it remains about 12% of the workforce. Indian manufacturing is on the low side for a country with its level of development.

In contrast, deregulation has worked. India’s position in the World Bank’s now-discontinued “ease of doing business” rankings improved from 142 in 2014 to 63 in 2020. This has spurred growth, and the Indian government is rightly doubling down on this approach. Although the deregulatory plans announced by the prime minister, Narendra Modi, have many elements, by far the most important will allow women to work more hours, undertake more factory roles, and work at night.

This matters because only a third of working-age Indian women have paid jobs. That compares with about 45% in Bangladesh, 60% in China and 70% in Vietnam. Matching Bangladesh’s rate would, arithmetically, raise Indian GDP by about 7.5%, taking into account the Indian male-female wage differential. Matching Vietnam would add a quarter to India’s national income. Both figures would be larger if better female job prospects persuade families and local governments to spend more on girls’ education, equipping women for better jobs.

Related articles:

All this is good news for India, but it will be good news for us too. Indian women are currently far less likely to work in factories than women in other Asian countries. A new workforce for Indian factories will not only raise local incomes, but also means competitively priced products for us. That is directly good for our standards of living, and ameliorating inflation here will also lead to lower interest rates, lower mortgage rates, and higher investment.

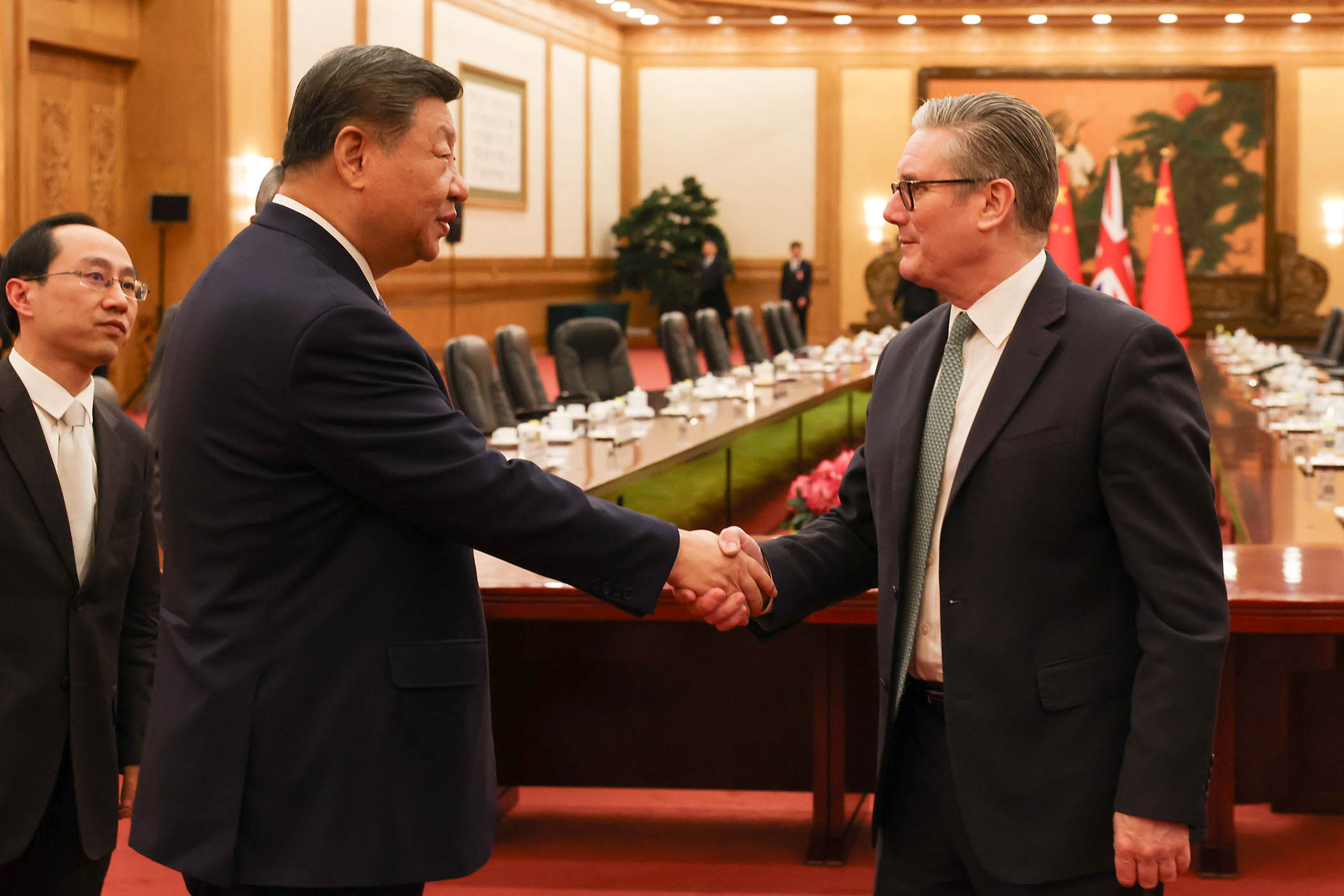

A more affluent India means there will be more Indians rich enough to buy things from Britain. The UK sells more than twice as much to China as to India – the potential for increasing exports to India as it gets richer, and an aspirant class emerges, is obvious.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

A more dynamic Indian economy is just what the world needs right now. It will be good for Indians and good for the rest of the world.

Photograph by Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg via Getty Images