On a rare escape from Whitehall, back when he used to be chief civil servant at the business department, Sir Alex Chisholm took part in mandatory helicopter escape training before a visit to an oil rig in the North Sea.

Participants are submerged in a pool in a mock helicopter cabin, often inverted, and must escape. The full course takes three days. Two of the other participants didn’t pass muster. The precautions required to visit a nuclear plant are less adrenaline-fuelled, but no less rigorous. As chair of French state-owned EDF UK, the main operator of Britain’s existing nuclear reactor fleet, Chisholm is familiar with the security checks, safety briefings and full ensemble of personal protective equipment needed to access the site at Sizewell B.

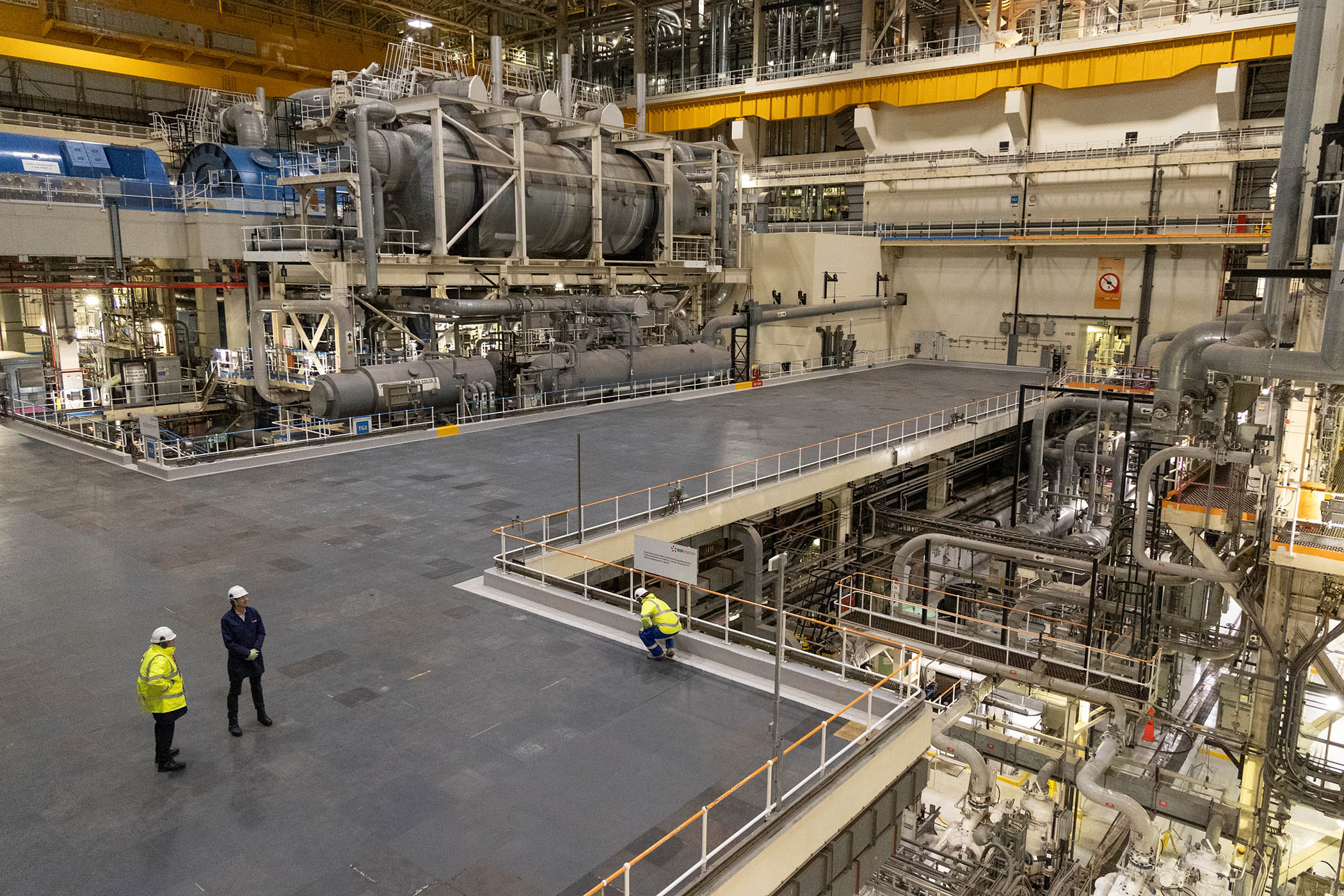

It’s a brisk, clear day on the Suffolk coast. We’re greeted by Niki and Gavin Rousseau, a couple who each had a parent working on the original reactor at Sizewell A, built in the 1960s, and who have been involved in running the current site since before it first started generating energy on Valentine’s Day in 1995. That day, more than 31 years ago, was the last time a nuclear power plant was completed in the UK.

Why the hiatus? Since the discovery of fossil fuels in the North Sea and the “dash for gas” in the 1990s, the UK’s nuclear capacity has shrunk, accounting for about 13% of the UK’s electricity today, down from 26% in 1997. Four existing stations, including Sizewell B, are now approaching the end of their lifespans, raising the risk that Britain could enter the 2030s without enough base-load power to meet surging demand from artificial intelligence and a growing population.

Part of the challenge, Chisholm claims, has been Britain’s sclerotic attitude to getting things built. “It has become harder to do business in this country,” he says, pointing to the example of a 55,000-page development consent order (DCO) that was required to get the go-ahead for EDF’s nuclear plant at Hinkley Point C in Somerset.

Late last year a review by John Fingleton, a former chief executive of the Office of Fair Trading, caused uproar by highlighting Hinkley’s £700m programme for protecting local aquatic wildlife – including an acoustic deterrent or “fish disco” – as an example of over-zealous regulation holding back growth.

“Of course, we want to take appropriate measures to reduce harm to fish. But £700m? It’s just way too much,” Chisholm says. “And the total amount of fish at stake is the equivalent to one trawler a year,”

Hinkley, which is majority-owned by EDF and is due to come online in the early 2030s, will produce 3.2 GW of power when built, enough to supply 6m homes and ideally providing a stopgap as other nuclear plants are decommissioned.

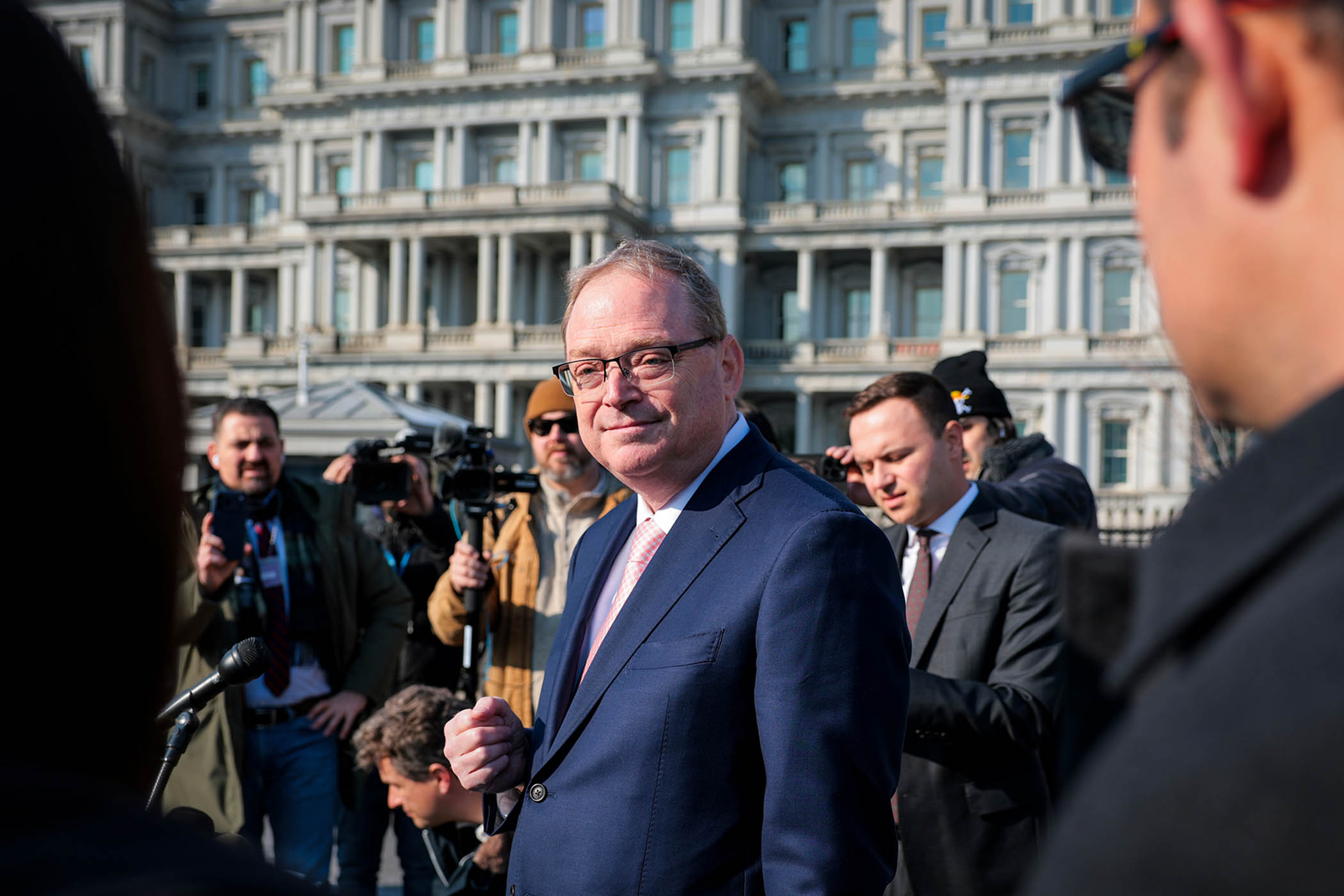

Alex Chisholm

But the project has faced numerous obstacles; running four to six years late and 2.5 times over budget at an eye-watering, inflation-adjusted cost of about £48bn. A former CEO of EDF, Henri Proglio, has described Hinkley’s design – the European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) – as “terrifying” and “almost unbuildable”. EDF points out that EPRs have been built and are operational in France, Finland and China.

In 2017, the National Audit Office released a report that found Hinkley Point C had “locked consumers into a risky and expensive project with uncertain strategic and economic benefits”, because of the government’s deal to pay a guaranteed electricity price of roughly £127 per MWh, adjusted for inflation.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But Chisholm is adamant that the worst is behind. He admits that “what it took to bring a fully capable supply chain back to life in the UK was probably greater than the company at first estimated”, but also says there is a “benefit from the fact that this has now been proven, and we can replicate the design and bring down the costs”.

EDF’s annual results on Friday revealed EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) last year of £1.9bn, down from £2.9bn the year before, as well as plans to invest another £15bn in the UK over the next three years. It is expected that much of that will go into Hinkley, which started construction nearly 13 years ago.

The lessons learned will be applied at Sizewell C, a project that was finally greenlit last summer. It will be built next to the existing Suffolk “B” site and will use much of the same design, supply chain and expertise as Hinkley. But there will be one key difference: this time it’s the taxpayers that are on the hook.

Under a pricing model agreed between the government and Sizewell C’s other shareholders, which include EDF at 12.5%, the typical UK household is already paying £1 a month on top of their current bills towards the plant’s construction. The government says the mostly debt-funded project will cost an estimated £38bn in real 2024 prices to build, but financial modelling used in the fundraising process suggests that could balloon.

For now, the view of the site from neighbouring Sizewell B leaves a fair amount to the imagination – it is mostly excavated earth and porta cabins. Sizewell C is likely to be operational by the mid to late 2030s, at the earliest.

What to do in the interim? UK domestic electricity prices are now among the highest in Europe, and it’s even worse for industry. Better battery storage and grid flexibility will certainly be required. But Chisholm also argues that a system reliant on nuclear and renewables will be less expensive than a “renewables only” path. This is due to “intermittency” – the dependence of wind and solar power on favourable weather conditions.

He says that future renewable auction rounds by the government, after the most recent in January, AR7, won’t have the same uptake. “I just don’t think we’re going to need much more renewables capacity. There is an upper limit on that. I don’t think we’re going to see another auction round on the scale of AR7.”

Britain’s dependence on natural gas could well increase by the end of the decade, he says, but the geology of the North Sea makes the economics of extracting much more oil and gas domestically difficult: “We’re not like America.”

Not surprisingly, he argues that the fail-safe answer is to eke as much out of Britain’s existing reactors as possible. That means extending the life of Sizewell B beyond 2035 to 2055.

Extensions have been approved for other reactors of a similar design. But an update to the kit to keep the reactor running beneath the iconic white dome of Sizewell B will be costly. EDF and co-owner Centrica have offered to invest £800m, but only if the government guarantees a long-term price for the electricity it produces.

Chisholm says this price would be “considerably less” than the £91 per MWh average “strike price” agreed for offshore wind developers at AR7, and that the company is keen to reach an agreement “pretty soon”.

How the government sells that to the taxpayer is another matter, especially at a time of pressure on the public purse. So, can nuclear projects ever really happen without the hand of state?

“Even for the very biggest funds out there, nuclear is big time. But do I think that in the future, there will be wholly privately funded plants, small plants? Yes.”

Although a “gigawatt” man at his core, Chisholm is surprisingly open to the role that small modular reactors (SMRs) of the type made by rival Rolls-Royce SMR could play in Britain’s nuclear future. EDF has even started its own SMR project on the old site of the Cottam power station in Nottinghamshire.

“Trying to look at it at the national level, and not selfishly at a company level, what’s the lowest cost way of providing that nuclear power? At the moment, I would say the jury is out.” Much depends on SMRs being proven at commercal scale.

And what about foreign stakes in Britain’s energy system? Ever since the government buyout of China’s state nuclear company, CGN, from Sizewell C in 2022, that has been an increasingly fraught question in the industry.

‘Even for the biggest funds, nuclear is big time. Do I think in the future there will be wholly privately funded plants, small plants? Yes’

‘Even for the biggest funds, nuclear is big time. Do I think in the future there will be wholly privately funded plants, small plants? Yes’

Chisholm says it is possible for Britain to have a “sophisticated relationship” with China, “where you don’t have to approve of 100% of what they do, it’s probably unrealistic that’s going to happen for any country. In some areas you say, look, we’re going to have an arm’s length relationship, and in others, you’re prepared to work closer together.”

As we carefully tread our way through the heat and hum of the turbine hall; an Escher-like maze of steel and warning signs, Chisholm’s enthusiasm for producing energy is plain to see. Gesturing with one wiry arm at one of the turbines, he yells: “One million homes, each of these!”

His interest was kindled during his tenure as head of the competition regulator and its investigations into the energy market. After that, in 2016, he took on roles as permanent secretary in the climate change and energy and business departments, before rising to become Cabinet Office permanent secretary in April 2020.

At a tumultuous time for the civil service, with strikes over pay and Chris Wormald having been recently forced out as its chief, Chisholm points to external stresses, rather than issues with the service itself. “The Cabinet secretary is very close to the centre of power, and that power has been extremely challenged in the UK. People speak about a ‘crisis of the British state’; we’ve gone through the financial crisis, Brexit, Covid, energy crisis. There have been a lot of challenging situations.”

He sees the churn in government reflected in the private sector. “The average tenure of the CEO or CFO has been getting shorter and shorter. That’s also telling you that in the modern world, running large organisations under pressure with a lot of expectations and scrutiny is a tough gig, so people are going through that a bit faster.”

Chisholm’s time as a mandarin taught him the value of “strategic patience” – few projects in government yield quick wins, with the notable exceptions during his tenure of the furlough scheme and the vaccine rollout.

A long-term perspective is needed at EDF, too, and one suspects that such a capital-intensive beast would not have fared well on the hasty public markets. For every £1 of profit EDF has generated since 2018, £2 has been invested.

As the post-industrial landscape outside Ipswich passes by on the journey back to London, the conversation turns to jobs – and the impact of Brexit. “The extent to which our model, when we were part of Europe, depended on importing labour and capital means that now we need to strengthen our ability to invest in our own workforce,” Chisholm says. He describes the UK as an “extreme outlier” in this respect and close to the bottom of the table in Europe. But EDF, as a European company, seems to have done a better job than most.

Owing partly to the scale and complexity of the project, more than 14,000 workers have passed through EDF centres of excellence at Hinkley, while apprenticeship schemes at Sizewell B and C are well-subscribed.

On the same day as figures released by the Office for National Statistics showed that UK unemployment had reached a decade-high outside the pandemic, while young people out of work number close to a million, Chisholm offered a diagnosis of where Britain could be heading.

“The combination of a higher skilled workforce and higher level of automation is going to mean that our productivity is going to go up. But there is an adjustment cost for the economy, because the number of new jobs being created is low.”

For all its challenges, there’s no denying that nuclear is an industry that has offered long-term stability to its workforce. There is at least one industry, it seems, where humans remain indispensable. The question is: how much are taxpayers willing to pay for it?

Photographs by Andy Hall