My son’s bed is something of a gauntlet. At the foot of his top bunk, ejected like rubble from a small earthquake, lies a pile of books I periodically clear away, only to find it restocked within a week or two. At seven, he’s thankfully too short for it to make much difference to his sleeping arrangements, and part of me finds his bibliophilia so charming I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I’m wary of fetishising reading for its own sake, since I find a lot of that conversation mildly puritanical. I was a bookworm, but several of my siblings were not, and all that taught me was that there are many different types of intelligence. That being said, child literacy numbers make for stark reading. In June last year, the National Literacy Trust surveyed 114,970 children and reported the lowest numbers ever recorded, with only 39% of girls and 25.7% of boys stating they enjoyed reading in their spare time. The reasons for this are likely to be multifaceted, and I’d imagine the tabloid bogeymen of YouTube and video games have had something to do with it. It’s just that when certain journalists bemoan a decline in reading for pleasure among children, I recall them having enthusiastically cheered on the very same government that’s shut one in five libraries in Britain since 2012, and ushered in a cost-of-living crisis that has made buying books prohibitively expensive for a huge swath of Britain’s population. Maybe they’re right, and today’s coddled tots are just illiterate morons poisoned by smartphones. Or, perhaps, their parents’ and grandparents’ generations set fire to every bedrock of literacy they themselves enjoyed, in a spree of vulgar ideological vandalism for which they now refuse to take responsibility. Who knows?

Friends sometimes ask me how my seven-year-old boy became so enamoured of books. I tell them I don’t know

Friends sometimes ask me how my seven-year-old boy became so enamoured of books. I tell them I don’t know

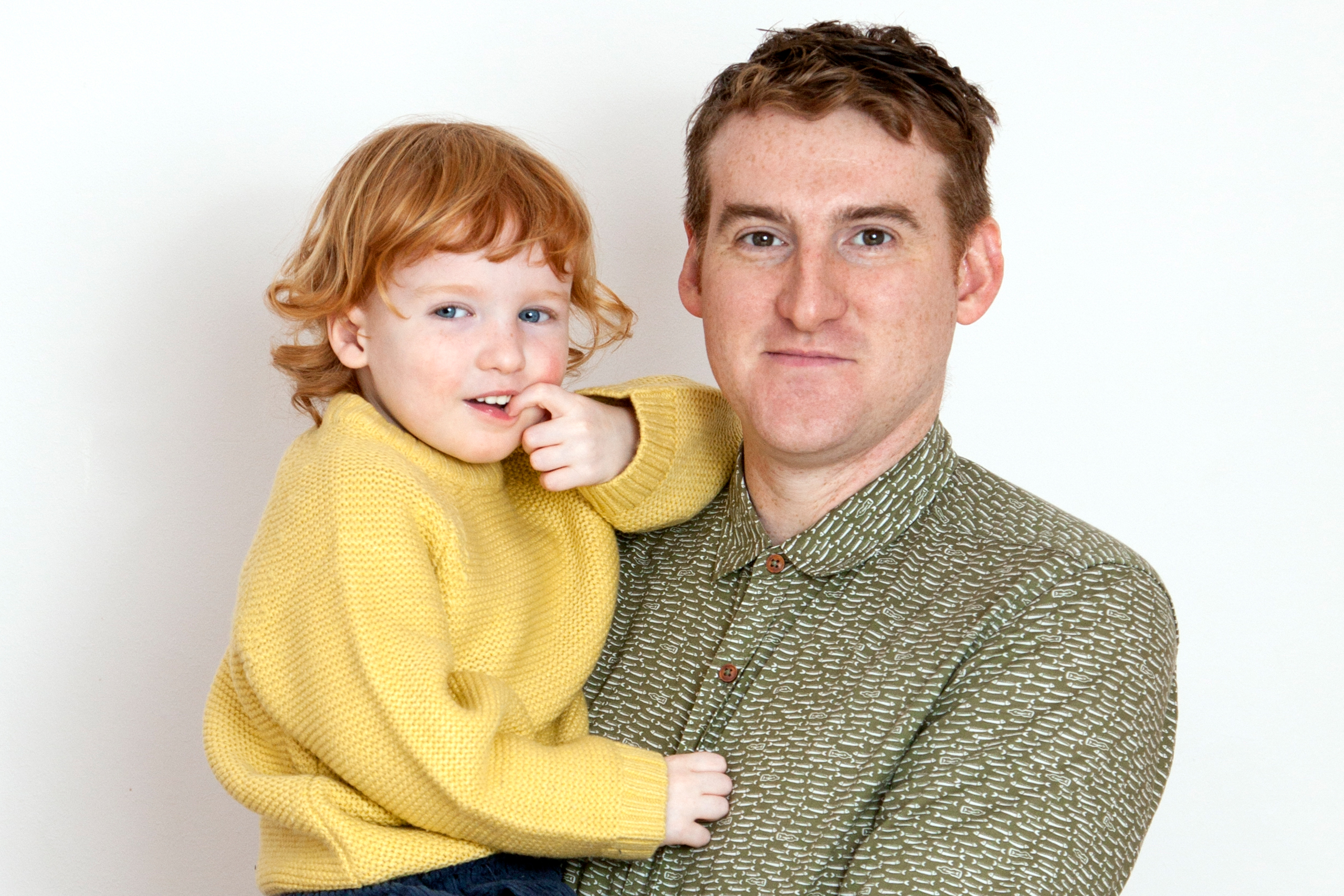

Whatever the case, when friends see my son reading so avidly, they sometimes ask me how he became so enamoured. I tell them I don’t know. I made a point of reading to him every night until he started grabbing the books off me, but he certainly enjoys screen time as much, if not more, than he does reading (a trait, incidentally, he shares with every writer I know). What I do tell them, however, is what books he’s loved most this year, in the hope his recommendations might spark that love in someone else.

A big favourite for 2025 was Loki: A Bad God’s Guide to Being Good by Louie Stowell, a retelling of Norse myth that brings the trickster God Loki down to Earth to live as an 11-year-old boy. There are currently three more books in the series which my son reports he is “1,000,000%” going to read next. He says it’s “very funny and very cartoony”. His favourite bit is when “Loki made a deal with the bad guys. Because he’s a bad guy. But he’s also a good guy.”

The duality of man is present in his favourite classic read of the year, too; Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. “I like that there’s bad and good characters,” he tells me. “Wonka is a good character, but sometimes bad, there are even half-good-half-bad characters, like the sugar girl who got captured by the squirrels… Veruca Salt. I said Sugar instead of Salt.”

His love for comics legend Jamie Smart has remained undimmed and he considers Bunny Vs Monkey: Intergalactic Monkey Business to be “the best yet” of the 11-book series, “very, very funny and based in space.” He’s also spent much of 2025 reading all of Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid books, the blockbuster series chronicling the life of American pre-teen Greg Heffley. His favourite was 2023’s No Brainer which “literally has scenes where his brain goes to school. I mean, literally, his brain can go into school, but he stays home, and then he can pop it back inside of his head so he can learn everything. his brain learned in school.”

Finally, he refused to co-operate on this list unless I included a perennial favourite from this year, the Pokémon Super Duper Extra Deluxe Essential Handbook. It resides not at the foot of his bed but under his pillow and, frequently, in his arms while he sleeps. When I tell him that this is, effectively just a book-length list of Pokémon and their stats, he replies, “But it has loads of facts and so many Pokémon – 1,008, to be precise.” What would you say, I ask, to those who think that sounds boring, or not particularly literary? “I’d say: ‘Do you even want to win a Pokémon tournament?’ You will with this book, because of all its stats!”

Touché, I guess.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy