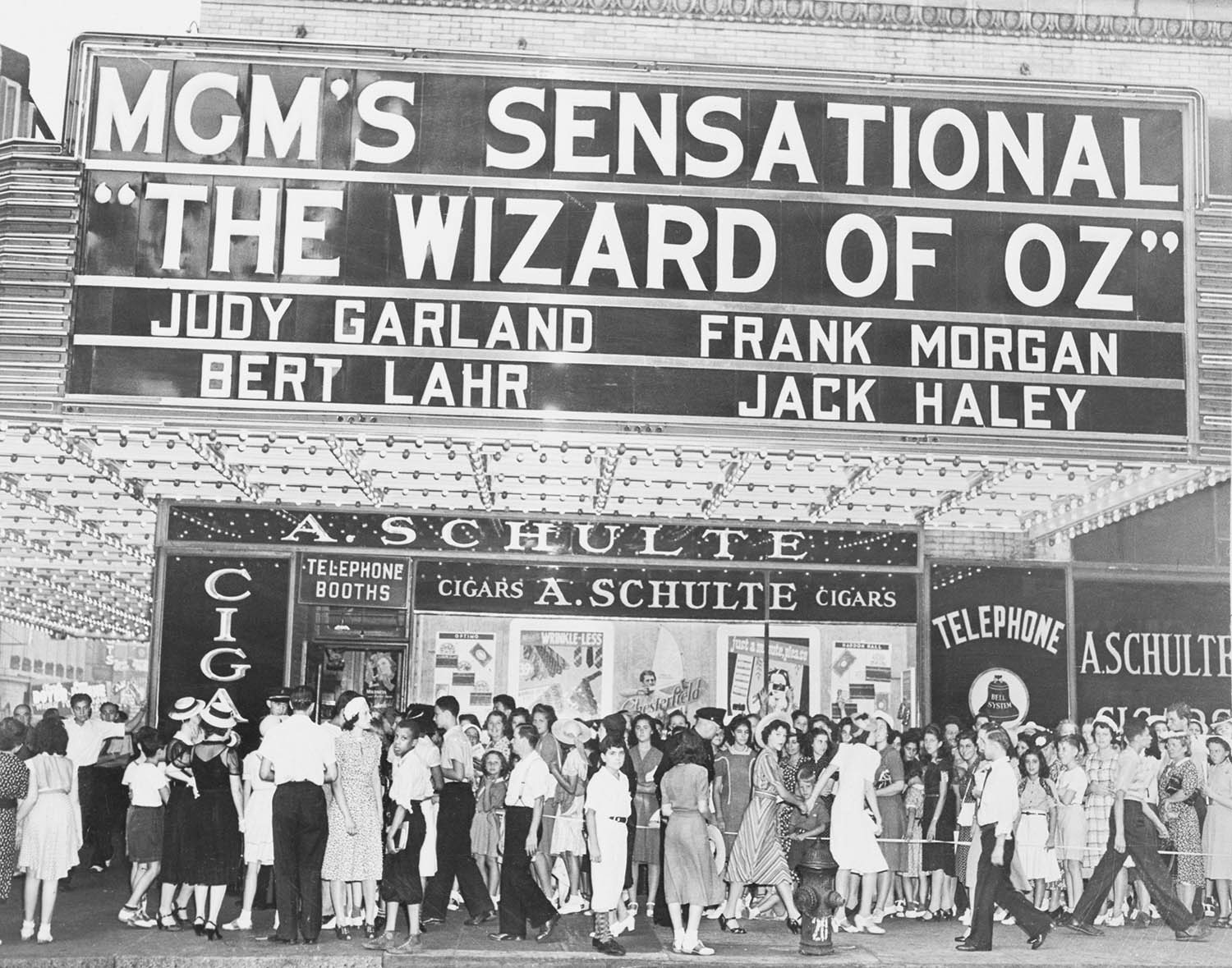

Who will speak up for the critic? After all, it’s so much fun to point out when we get it wrong. What film weighed “like a pound of fruitcake soaking wet” on its release? Why, The Wizard of Oz of course, that famous dud. (Thank you, Otis Ferguson of The New Republic.) Here’s the Spectator raising a venerable eyebrow – “the incidents are too coarse and disagreeable to be attractive” – in considering Wuthering Heights at the time of its publication.

The list of art in any form that has been ill-received or misunderstood in its day is an endless one, and criticism must always be subjective. But critics and criticism are increasingly under threat, and we must come to their defence.

Last month the New York Times announced that four of its sharpest and most respected critics – Margaret Lyons, TV; Jon Pareles, pop music; Zach Woolf, classical music, and Jesse Green, theatre – would be “taking on new roles”. A memo to the paper’s cultural staff announced that “our readers are hungry for trusted guides to help them make sense of this complicated landscape, not only through traditional reviews but also with essays, new story forms, videos and experimentation with other platforms”.

A few days ago, Associated Press announced that it would not be running any book reviews after 1 September. Its book reviewers received this bleak reasoning from Anthony McCartney, AP’s global entertainment and lifestyle editor: “The audience for book reviews is relatively low and we can no longer sustain the time it takes to plan, coordinate, write and edit reviews.”

I’m not here to make an argument about economics. I’m not even here to argue against essays, new story forms, videos and experimentation – hurrah for all of those things. I’m here to argue in favour of – well, being human. Knowledgeable and expert critics give context for the culture in which we live; at their best they understand what came before and they consider what might come after. They appreciate form and relish novelty. People make art to express themselves and comprehend the world: critics build bridges between that art and those who would expend their time and money engaging with it. This is itself, and in the world we live in now, priceless.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

It’s shocking to me that in some quarters expert criticism has come to be viewed as “elitist” when in fact it is just the opposite. A great critic opens up worlds for readers, viewers, listeners, and makes them feel less alone.

We can all express our opinions these days. That’s fine. But a great critic can inform those opinions and enrich them. I learn more about how I can think about the Scottish landscape artist Andy Goldsworthy by reading what Laura Cumming writes about his work in this very paper. And much as I’d love to travel to Edinburgh to see his show there, if I can’t make it, her knowledgeable words give me a true taste of what I might find.

Although I’m a literary critic myself, I struggled to put my finger on what really bugged me about Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life; Parul Seghal, in The Case Against the Trauma Plot, a fabulous essay in the New Yorker, allowed me to understand the novel – and myself.

It is a truism now to say we are bombarded from all sides by information and opinion. The critic is the filter, separating signal from noise. They help us value what we make. Let us value them, in turn.

Photograph by Bettmann Archive