My personal goals for 2025 were platitudinously straightforward: to work harder and to get outside to fix my growing screentime. Since the pandemic, the hours I’d spend staring at my phone had started to creep up and up, to the point where I’d begun to dread the Monday morning summary of my average for the previous week. It’s a story you’ve heard before. A study from 2024 found that 45% of Gen Z and 39% of millennials were actively trying to reduce their screentime, a number I can only imagine is increasing daily. My rationale had less to do with being anti-phone – I don’t think every second spent on a screen is inherently harmful – but more to do with the free time I was losing. There was a richer life being sacrificed for what was mostly a mind-numbingly bad habit.

The prevailing argument for how to resolve phone addiction is that all you need to do is just stop. Find a way to put it down, embrace the silence and feel your brain cells magically regenerate. We’re told it’s a matter of grit and discipline, something most of us simply lack. There is now a thriving industry of apps and technology dedicated to getting you off your phone, which operate on this vague assumption. Companies such as Brick, Minimalist Phone and Opal promise to switch off your social platforms or lock you out of your phone entirely. Our actual devices and social media apps also offer screentime limits where a notification will appear telling you your time is up (one that’s easily dismissed). This, they say, is the way to reclaim hours of your life and undo the brain rot that’s making you more stupid.

These interventions do work for some people. (The effectiveness of going cold turkey can be seen in the rise and popularity of dumb phones.) But for most, they serve as a Sisyphean torment: that, even if you do briefly log off, you find the nothingness excruciating and are struck with how badly you are itching to return. You’re also confronted with frustration and shame – left wondering how, as a fully grown adult, you’ve ended up with a child’s attention span. These apps might know what gets you off your phone, but rarely do they offer something that kills the desire to keep going back.

My experience this year wasn’t dissimilar. Using blockers and time limits, I initially succeeded at trimming an hour, then another 30 minutes. But the remaining time that stood between me and my two-hour goal was being clawed down minute-by-minute. What got me there in the end had nothing to do with willpower or self-flagellation – and especially not with notifications that came with an option to snooze. It was an accidental leap: when my aunt came to visit in October, she gifted me needles, yarn, her expertise and a new rhythm of life.

Despite a severe allergy to most things trad and twee, in knitting I have found what I can sincerely call a passion. It has me up early before work, stitching in the dark, often in happy silence. It’s how I fill every idle moment; often feeling the click of needles in the time in-between like a phantom pain.

What I didn’t mean to find was a way to decimate my screentime. After two weeks, the time I spent scrolling had halved. My keenness to check emails or Instagram had, in all seriousness, evaporated. The time I spent online became more enjoyable, increasingly taken up by knitting Subreddits and YouTube tutorials, scrolling essay-length posts debating yarn quality (no acrylics or superwashes here) or critiquing the new Tom Daley knitting show (lengthy, detailed work doesn’t seem to make great TV).

The value of knitting can be found in the growing evidence that creative activities slow down brain ageing – or in the fact that it is a practical skill that may benefit me the rest of my life. But the real appeal of knitting, for me, is that I wouldn’t care if it was secretly poisoning my body or damaging my personal life (other casualties do include my reading list and professional productivity). It’s that, most of the time, I want to do it more than anything else. I’ve found an obsession where any self-improvement perks are secondary to the draw of pleasure and fun.

In all the discussions about how to resolve our reliance on screens, an austerity mindset has drowned out a far more effective argument that, rather than punish ourselves, we should pursue the thrill of something new – an activity that effortlessly reshapes our attention without us even noticing. When you train a dog, you learn bad habits are resolved by incentivised alternatives. Barking at the door? Teach them to grab a toy. Jumping on guests? Hide treats in their bed. This animal logic applies to us, too. You’re not going to create fulfilling routines only through cutting back to zero, but by reaching out into the world and finding a thing that leaves you with no choice but to make room. This discovery may involve trial and error, and not giving up when the answer isn’t obvious. Good luck has meant I can’t claim this kind of dedication. (Friends reading this will laugh at how badly I’ve managed to disincentivise my own dog’s rambunctiousness.)

Related articles:

It may be that the promise of white space is enough to get you off your phone. Practising that discipline – even embracing boredom – is a worthy ambition. But if, in 2026, you want to do less of what makes you feel bad, the solution won’t be found in punitive acts of self-control. It will be in the abundance of answering: what’s out there that makes you want to do more.

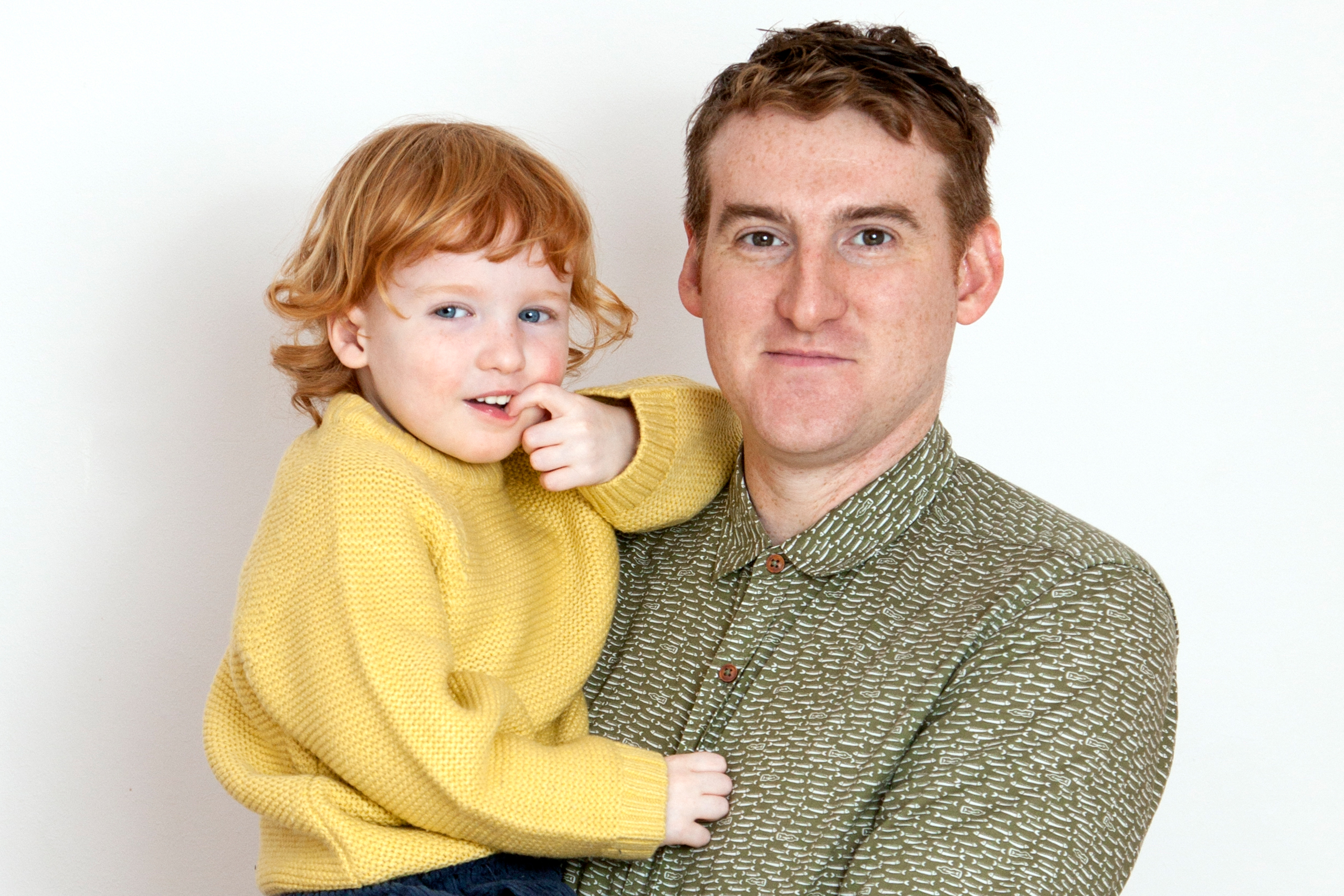

Photograph by Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy