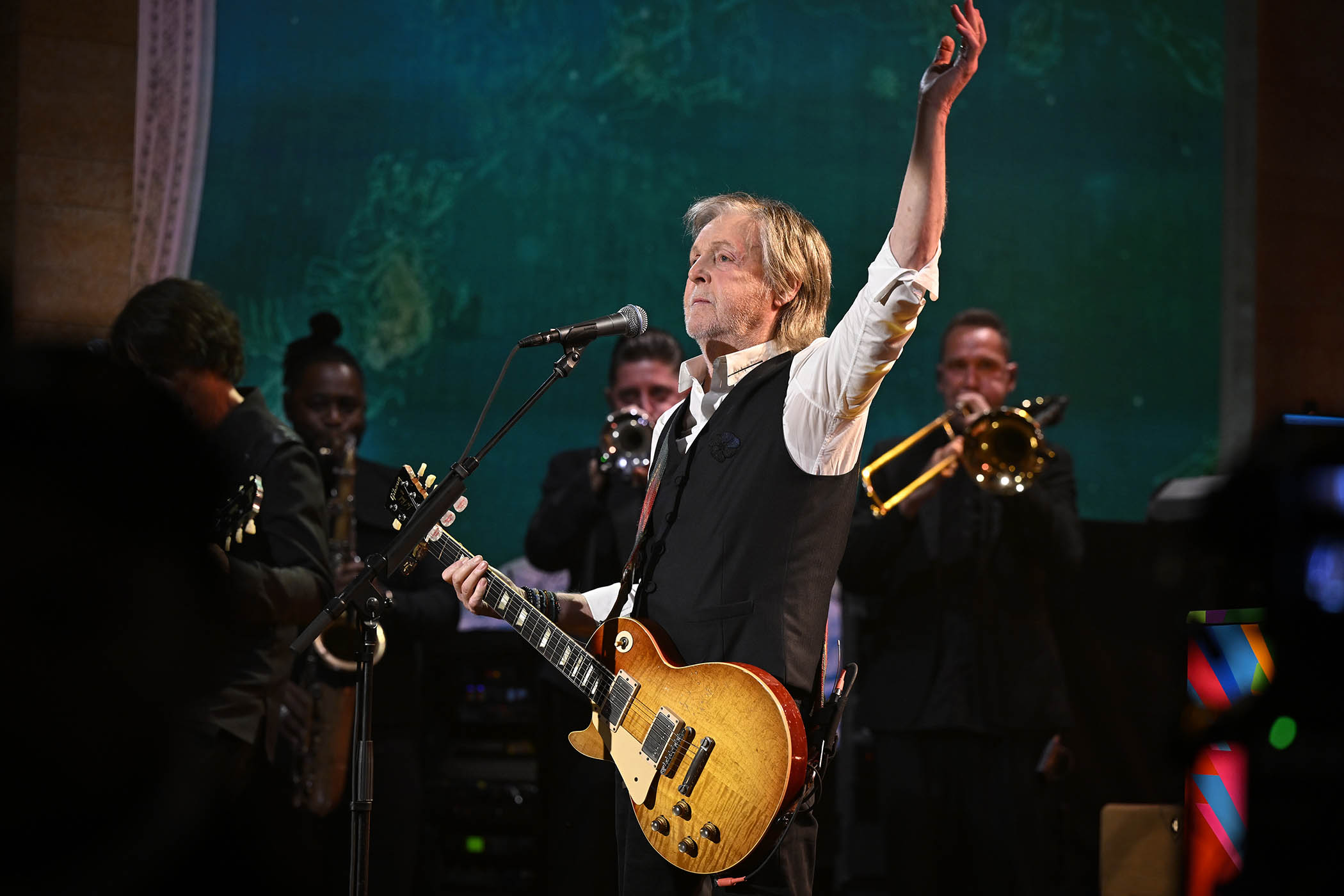

Have you heard Paul McCartney’s latest song – his first in five years? No? What a pity. It’s a silent song. All you can hear is a faint hissing sound and some background noise. It’s part of an intriguing new album, Is This What We Want?, embodying part of a groundbreaking protest against AI by releasing the release of a silent album featuring recordings of empty studios, involving more than 1,000 musicians.

The idea was triggered by the realisation that the products of supposed generative AI have only been made possible by the largest case of corporate theft in history. The tech industry that began in a great burst of technical creativity in the 1960s and 1970s gradually morphed into what it is now: a purely extractive industry – just like mining and oil. Initially, it was content just to mine our time and attention, but now it has moved on to appropriating the intellectual property of creative artists on a global scale.

The strange thing was that, for a time, it looked as though the industry would get away with this larceny. Some corporate bodies such as the New York Times and Getty Images went to court, and the Writers Guild of America launched an effective strike against Hollywood studios salivating at the thought of getting rid of pesky human writers. But, for the most part, individual writers, artists and musicians huddled miserably and pondered vanishing incomes, and the difficulty and expense of taking corporate looters to court.

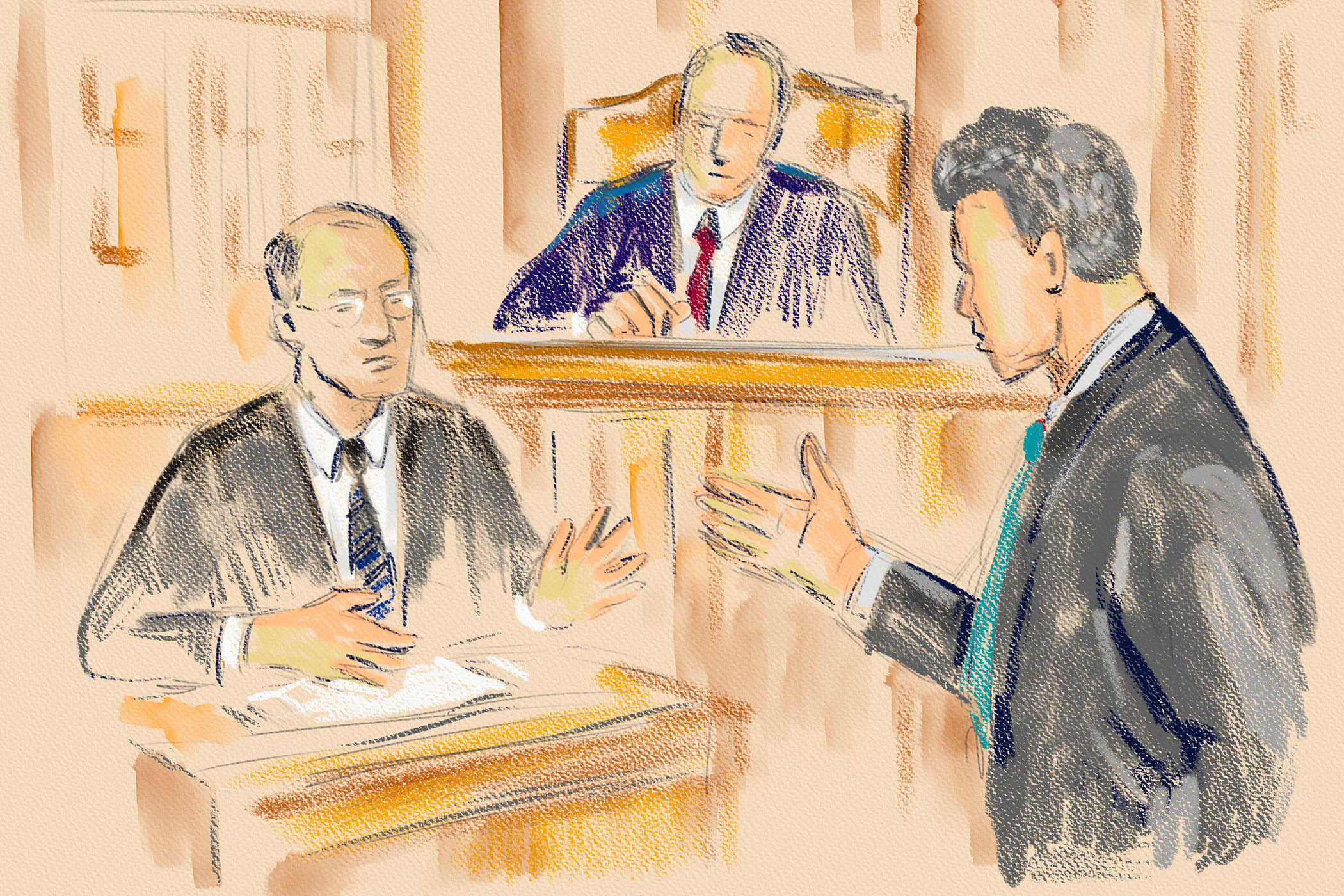

And then came an apparent breakthrough. In August 2024, a group of American authors filed a class-action lawsuit in a US federal court against the AI company Anthropic. They alleged that it had used hundreds of thousands of copyrighted books, many obtained without permission, to train its Claude large language model. They also claimed that Anthropic had acquired the books from supposed “pirate libraries” such as Library Genesis and Pirate Library Mirror, without licensing or consent.

In June, the judge ruled that using digital copies of the plaintiffs’ books to train the AI – namely, feeding them into a model that learns patterns rather than simply republishing the text – was permissible under the “fair use” doctrine in US law because the training was “exceedingly transformative”. But he also ruled that Anthropic’s large-scale downloading and storage of pirated books to build its central library was not protected by fair use and so should proceed to trial. At which point, Anthropic decided to settle for $1.5bn. The authors of the 500,000 pirated works (one of them this columnist) would receive about $3,000 each.

At first, it looked as if this case might set a useful precedent. Well, maybe it does for the US, but not for other jurisdictions. The UK, for example, allows only narrow, specific “fair dealing” exceptions. It permits unlicensed copying only for tightly defined purposes: research and private study, quotation, criticism or review, and caricature, parody and pastiche. And it allows text and data mining only for non-commercial research. Anything else requires consent of creators – and payment if desired.

Naturally, this infuriates tech bros such as Matt Clifford, the author of the UK’s government’s AI strategy, section 24 of which contains the preposterous claim: “The current uncertainty around intellectual property (IP) is hindering innovation and undermining our broader ambitions for AI, as well as the growth of our creative industries”.

Just for the record, there is no “uncertainty” about the UK law. It says: no copying for commercial purposes without consent and – if required – payment. And given that training AI models involves hoovering up data at an unimaginable scale, these kinds of niceties impose friction that would bring the machines stuttering to a halt. So the government, which has signed up to the Clifford plan, has embarked on a consultation (AKA cunning plan) to lull anxious authors into compliance.

Its favoured proposal is: “A data mining exception which allows right holders to reserve their rights, underpinned by supporting measures on transparency.” What that would mean is: “AI developers would be able to train on material to which they have lawful access, but only to the extent that right holders had not expressly reserved their rights.”

You can guess how this will pan out. UK copyright holders will have to devise ways of opting out that will deter American tech giants from stealing their property. It will be like the “robots exclusion protocol” that people put on their websites to deter web-crawling bots. It works sometimes – but only against polite scrapers. Against determined or commercial scrapers, it’s weak and easily bypassed. And it’s not legally binding. Any UK opt-out protocol will be just as feeble – unless it’s backed by legal enforcement.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Which brings us back to McCartney’s silent song. If legal protections won’t come from governments captivated by AI promises, perhaps the only power creators have left is the power to withdraw – to create silence where tech companies expect content. It’s a form of creative civil disobedience: you can’t train your models on what we refuse to create. The question is whether enough artists will join the protest before it’s too late.

What I’m reading

Ex machina

The Vatican Is the Oldest Computer in the World is a lovely metaphor examined by Andrew Brown.

Trying times

A nice essay by Arthur Goldhammer is Perseverance in Despair, which attempts to find light in the prevailing darkness.

Fall guy

Are We Doomed? is a masterly essay in the London Review of Books by David Runciman on population collapse.

Photograph by Todd Owyoung/NBC via Getty Images