To celebrate turning 18, my nephew enlisted in the US Army. Six months later – after the last presidential election and so much else had been decided – I travelled to Fort Moore in Georgia (now called Fort Benning) to watch Giovanni graduate from bootcamp. Giovanni did not yet know me on testosterone, and I could only guess at the kind of man he had become. I walked past the packed bleachers in my purple sunglasses and flamingo shirt, craning my neck for a glimpse of my nephew, and was keenly aware of all the eyes on me – of the unavoidable softness of my body. I have a beard. My jaw is square, like a man’s. I wear makeup and earrings. My voice is deeper than you’d expect, but I mostly still go by Annie, especially around family. No one at the base – or anywhere I had been in Georgia – looked anything like me.

The troops came in marching to the theme from The Last of the Mohicans. My nephew was the tall one at the front of a column. Most of the boys were white, not quite out of their teens, and they reminded me, in their rows of shorn heads, of Lego figures. When they began the Soldier’s Creed, I heard Giovanni’s voice, or thought I did. I felt a ripple go through the stands, the audience straightening up, as if to be more worthy of these boys.

To start the formalities, the military fired off green and purple pyrotechnics that, for any gay person, conjure the musical Wicked. Then a squad jogged out to display a muzzle-loaded mortar system capable of firing 30 rounds a minute “indefinitely”. The soldiers raised their weapons towards the audience; the announcer repeatedly used the word “enemy”. When he explained that the cannon had a range of almost two miles, I tried to peer through the hazy future to the person who would stand at that distance from Giovanni. They were starting the Turning Blue ceremony, which marks the moment when a recruit completes their training and is inducted into the infantry. My nephew, like every other soldier here, wore a blue cord on his left shoulder to announce what he had put his body through during these intense months of training and, I suppose, as a promise of what he might yet endure. Now, one of us would have to pin the cord on the right shoulder while he stood to attention – a symbol of how the US Army is built on family. I heard them announce all of this, but I was surprised to find myself moving with the crowd towards Giovanni. Awash in siblings and cousins and veterans shouting and crying, people in uniforms or sweatpants or jewellery, I kept telling myself: “He loves you. You’re his Aunt Uncle.”

D/Annie Liontas and their nephew Giovanni Burke

Giovanni and I had texted while he was away and talked on the Sundays when his disorderly company was given phone privileges – so I knew all about the bunk searches, the skirmishes in the barracks, the scuffle with the kid over bread rations that led to mop duty, the marksmanship test he passed and, how on a 16-mile ruck, Giovanni carried his M4 assault rifle until mile six and then switched to the M249 light machine gun. “This is hell,” he had joked. “I can hardly walk on my feet!” I knew, despite all of this, that he aspired to come back for ranger training. I saw how proud he was, that he had achieved more than he thought possible. I also sensed that he admired certain aspects of my life, including that I was a writer and had published books, even though he had never really read a book in its entirety. But I did not know what Giovanni’s face would do when he saw me. If we would now be strangers to one another, across enemy lines.

The night before the ceremony, the women in my family and I met at a nearby seafood joint whose motto is: “When life hands you lemons, squeeze them on a piece of fried fish.” The locals at the fish fry – that is, everyone eating dinner – turned their heads to stare at my wife and I: me in a burgundy pleather jacket, she in bright trousers, both of us looking like we had just stepped out of To Wong Foo. Homesickness overcame me – that old ache for familiarity, belonging. I avoided looking anyone in the eye. I tightened my face, as I often do in such moments, as I imagine Giovanni does whenever he presses the barrel of a gun against his chest.

Then a server came by and gushed: “I love your style.” The woman who took our drinks order smiled at me, too – her eyes saying, welcome – and added: “Don’t sleep on the key lime pie.” In Trump’s second presidency, I found myself stunned yet again that Georgian hospitality extended to someone like me. Sure, there were plenty of hard looks, scowls on the airport bus and in public bathrooms, but at the car rental centre, at the military base’s thrift store and Starbucks, I had been touched by how friendly people were.

Only a week ago, in my home city of Philadelphia, a mother yanked her child away as I passed by on the narrow pavement, glaring at me. Not long before that, a man in Philly saw my wife and I holding hands and yelled “faggot” so aggressively into our faces that I instinctively pulled her closer to me on the busy street. Another time, when I was walking my dog in my neighbourhood, a religious woman shouted: “Are you a man or a woman? Do you have a dick or a vagina?” When I tried to talk, she said: “What you are, it’s disrespectful to women.” She believed I was a man masquerading as a woman. She didn’t know how right she was.

All of this was a jumble inside me on Giovanni’s graduation day as I made my way through lines of soldiers, the smell of sulphur hanging in the air, the sound of training grenades in the distance.

We are not a US military family – we are immigrants – but we all guessed that Giovanni would enlist one day. When he was five, he showed up at my house for a sleepover in fatigues and dog tags, head shaved, as if bootcamp had already begun. At the coffee shop in the town where I lived, not far from the university where I worked, my nephew drew looks. An older woman tutted, and a couple evaluated me, wondering what kind of parent would put a child in a uniform.

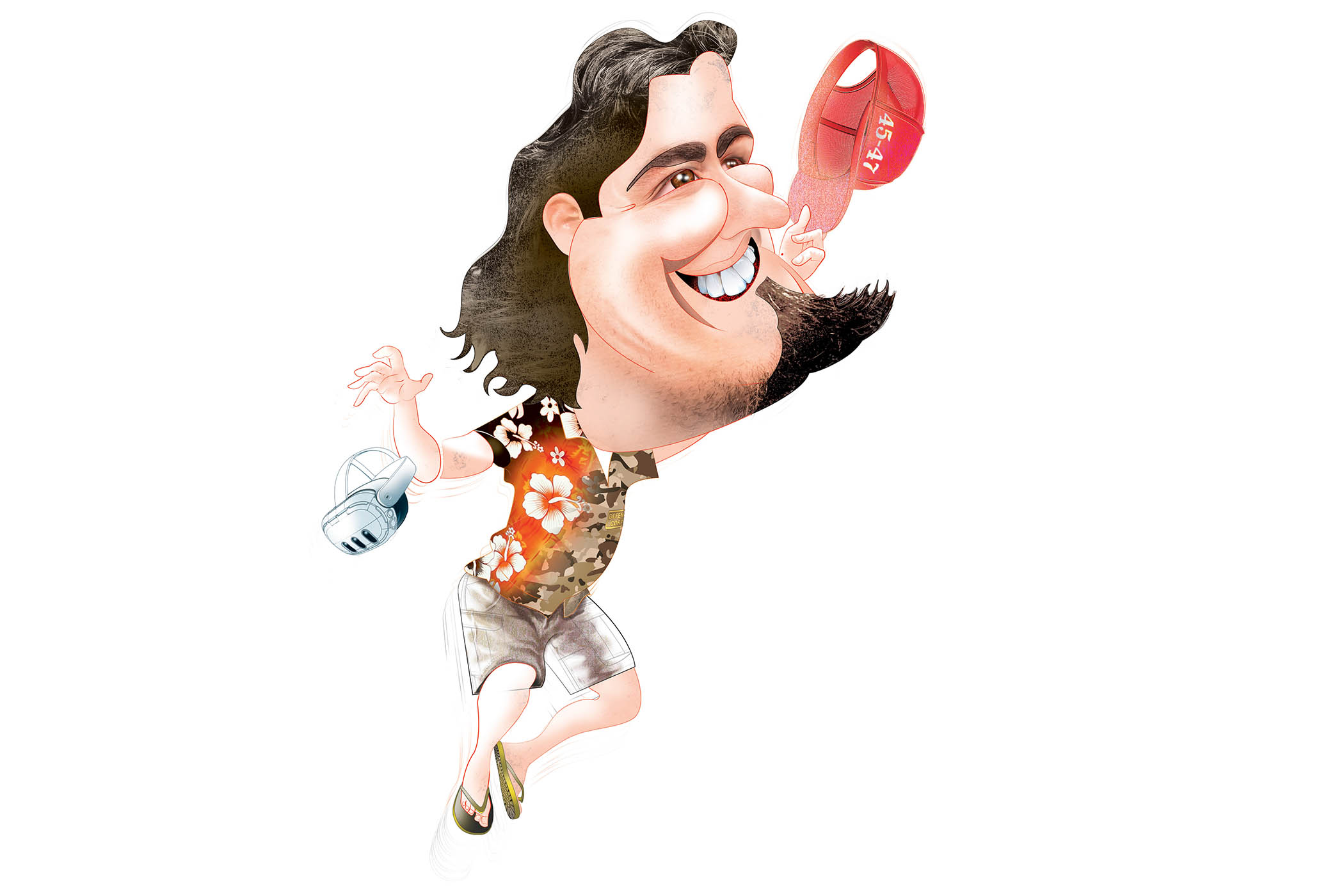

A relaxed D/Annie Liontas

“Why do they keep staring at me?” Giovanni asked, his little blue eyes widening.

I did not say that these adults were not accustomed to seeing children in camouflage, or that, in their eyes, he teetered between “fringe militia extremist” and “child soldier”. I did not know how to explain that people only scrutinise your appearance as a way to clock what’s hidden from view – that which they have failed to domesticate – and that with these sideways glances, they were trying to get a glimpse of the wildness in the boy. For these liberals – these women in their colourless colours, these men with their tendency to look over everyone’s heads – my nephew was as disposable as the paper sleeves on their cups. They marked him like so many other young American men, expendable precisely because he was not one of their own. I told Giovanni: “People often stare at what they don’t understand, especially when that’s other people.”

And what answers would I give him now, when I crossed the field and we met eye to eye? Who would we be to one another?

Giovanni knew I had started testosterone. I had confided this to him when we last saw each other six months earlier, at the dusty playground where we hung out to celebrate that his youngest sister was cancer-free. That day, as a family, we had rung the bell that announced our good news to the world: the three-year-old we loved was not going to die.

While my feral nieces, Sage and Charli, ran from swings to bright green climbing bars, Giovanni eyed me up, asked: “Why is your voice so deep?”

“Why is yours?” I joked.

I was alarmed. While most of the changes my body was going through weren’t visible, it seemed that he could hear somebody new in my voice. I tried to brush it off, not wanting this day to be anything but easy celebration, but Giovanni pressed me. Here was the one person in my family who saw who I really was long before I was ready for any of them to notice. I confessed that I was undergoing hormone replacement therapy.

“T?” he said.

“You know about T?”

“Guys at the gym,” he replied. “They go off.”

I had heard about these men, could easily picture them in bulging shorts and tank tops so loose they looked like rags hanging from their thick necks. I imagined one of them sticking a needle in his thigh so he could put on more muscle: to defeat all traces of weakness, humanness. The bursts of rage Giovanni was alluding to would follow the guy home to his wife or kids or job, or to the office of US Secretary of Health and Human Services.

“Why?” Giovanni asked. When I didn’t reply right away, my nephew shook his head as if I had just shoved him for no reason. He looked over at the yellow slide where his little sisters were playing, and I could see him trying to work it out. He said: “I didn’t know you were one of they-them.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Giovanni didn’t quite get it – or maybe didn’t get me like he once did. He’d had, at his last job, some conflict about using the right pronouns for a co-worker. Like his father, he listened to [the rightwing podcaster] Alex Jones, was curious about conspiracies, scrolled daily through a social media feed that was full of violence and beheadings. The dusty playground, where he had played as a child and where I had played, was not far from the high school in South Jersey we had both graduated from. It sits in a town that is 95.2% white and in 2023 was cited for excluding nonbinary and gender nonconforming people from applying for marriage licenses – which, if I look back to my childhood, actually feels like progress.

At the playground I could see in Giovanni’s eyes there were more questions than denials – how he was working towards something, rather than against it. Once, when we were painting his room, he’d asked: “Why are gay people the fun ones?” He had meant me, my wife, but also our chosen family – those queers with the instinct for looking more closely at one another for undisclosed danger or affection, and who see what Giovanni often tries to override: the real him, curious and gentle, desperate to take care of the world so he can be sure of his place in it. That Giovanni was here with me, playing tag with his little sisters, making sure neither of them fell off the swings. At the top of the yellow slide, before Giovanni went down and I followed, I told him that I hoped I could help him better understand people like me. In my voice, a plea to give us time.

That night, he texted: “It’s just the whole voice thing. [I know] it’s weird but I miss your voice.”

At the parade ground, weaving between all of the families taking photos and crying, I thought about what it would mean to lose my nephew. In the phone in my pocket, in my favorites album, there was a photo of us eating the breakfast cereal Fruity Pebbles together; another of us in a photobooth, me pretending to eat his ginormous head. In my heart, the memory of him kicking his long naked legs into the darkness as I lifted him out of his cot, a child that never could stay still. Sitting in the back seat of a car in our hoodies, listening to the rapper J Cole. Trying to train my cat to be more like a dog. The time he revealed he was a little in love with tap dancing. The afternoon we went to the nautical museum and he encountered an exhibit on slave ships and asked: “Why would someone do that to another person?” The funeral for my father, the grown-ups trying to convince each other how good he looked laid out in the casket, how sympathetic death had been to a welder, until pre-teen Giovanni said flatly: “Pop looks awful.” Also, that terrible fight we had, when Giovanni kicked the door off its hinges. I stared him down, almost two feet shorter than this sixteen-year-old boy, proclaiming: “I’m not afraid of you.” I had taught high school, I knew that teenage boys were creatures whose eyes flashed in the darkness, but who really just wanted to curl into your lap. I was not afraid of Giovanni’s anger, nor the violence coiled inside him, nor the hot tears that followed when he shook in my arms, but I trembled thinking of the long, winding future: how manhood might eventually come between us.

Burke received a special pass for the US Army’s 250th anniversary parade on 14 June 2025

When I finally reached Giovanni on the grounds, it was all over: he was a soldier now. My sister touched his shoulder – the “tap out” that was the military tradition that ended basic training. Standing in the sunlight among the cut of uniforms, he was brimming – as was I. My nephew was thinner, sharper, his upper body taut as a bridge, but his eyes were melting. He closed them when he hugged his mother. He had missed her, as all the boys had longed for home. Then my nephew – this new man still not quite recognisable to himself – took me in: my changed body, my unexpectedness, looking at me as if I stretched into the horizon.

He winked and said: “You look badass.”

Later, when we were eating chicken and waffles at the diner near the base, he told me how jealous he was that I could already grow a better beard than him.

After Giovanni comes home, we go to a gun range together; I’m one of those queers who shoots a weapon for the first time in 2025, convinced this is something I will have to know now. In our shooting lane, a paper body zips 50 feet back, recognisable as human only by the shape of the head, the ears. The heart, surrounded by concentric circles, is an oblong with an X through it. I hardly believe it when my first bullet goes right through the chest. Other shots miss. Fighting the recoil of the gun, I think how the next hundred days – and the hundred days after that, and the ones after that – will require not only imagination but more tender, perhaps startling, acts of connection. Our allies may not be the people we believed them to be; our enemies may surprise us by being more like us than we ever thought possible. My nephew is one of the people teaching me this. He lines up behind me, showing me how to position my fingers along the handgun’s barrel, where to tighten so my arms stop shaking. I watch him riddle the body with holes. I watch him sweep up the casings for the men behind the counter, thank them on our way out.

Afterwards, over pizza, we talk about all the old stuff – God, country, women. He describes how he made it through basic training, saying: “In order to keep pushing, you need to remember who you were back home and never want to be that person again.” He confesses to having startling dreams, wherein people who love him come after him saying he doesn’t belong here any more. He talks about actively enlisting, excited by the chatter around Syria. He tells me more about ranger training, which entails mountaineering and jungle/swamp survival. He confides his plans to toughen up his brother, a 10-year-old high-achieveing student who is the equivalent of a hermit crab searching for its shell. Make Benito into a man, like him.

Our enemies may surprise us by being more like us than we ever thought possible

Our enemies may surprise us by being more like us than we ever thought possible

But this last point, I fight him on.

“I don’t want to live in a world of people exactly like me,” I tell him. “No one would have any skills and nothing would ever get built. But I also don’t want a world that’s only people like you.”

Giovanni thinks for a moment, then concedes. “If there’s only me in the world,” soldiers, he means, “we’d just go around killing everybody.”

In time, National Guard troops will fill US cities. These soldiers, walking in twos and threes, will be some of the first people I see on my morning commute. They’ll be on the campus where I teach, walking among the students. When I encounter them, my first impulse will be to look away; my second, to search their faces for my nephew.

When I wrote about Giovanni in a poem entitled From Aunt Uncle to Private First Class, Delta Company, I wasn’t sure how he would receive it . Giovanni texted: “I am truly speechless and may or may not have a few tears in my eyes.” He later tells me: “Out there, I don’t get people like you, but I want to hear what you have to say.” He uses the word love. I cannot say it will always be this way with us, this closeness between brothers, but I hope so.

The day the president throws a $45m military parade on his own birthday, Giovanni will be at the front of the crowd, somehow having scored a special pass. He’ll send me a photo of the people behind him, crammed against the metal barricades. He’ll send another of the Washington Monument, pale and lit up at night – his first time seeing it. When I tell him you can spot it from my school – that often I look out of the windows, and there it stands, grey and unconquerable – he’ll call me from DC. He’ll be with friends, eating on a street corner, but we’ll talk for a while. His voice will go off like fireworks, my nephew excited to tell me about his first road trip, the tanks, the honours for the military, how close to the president he got, and I’ll be miles away in Philadelphia, listening.

Photographs courtesy of D/Annie Liontas, Bomb Magazine, Getty Images