Photographs by Karen Robinson for The Observer

It is Mother’s Day 2025, and in honour of the day, my two sons and my husband agree to come for a walk with me on a beautiful hilltop near our Dorset home. Normally, everyone is too busy, and I walk the local chalk hills alone (except for the dog), but today we are five. We park at a nature reserve and drift southwards along an ancient trading path, with the boys throwing a stick for the dog.

I keep one eye on the ground as we walk along the edge of a ploughed field, out of habit. I have been collecting prehistoric stone tools from this area for 20 years, and you never know when one might gleam up at you. We have found things that may be as much as 10,000 years old on these hilltops, and sometimes the flint comes up so clean and fresh it might have been dropped yesterday.

My husband abruptly reaches down and picks up a large stone. He holds it out to me. I am the arbiter of flint tools in our family; I am the one who decides whether they are worth lugging back home.

It’s dusty and quite yellow. The patina on it – the pale, outer layer – is strangely thick. The tip is gone, but it looks as if the break is old.

The stone reminds me of pictures of old axes I have seen in news stories from Africa and the Middle East. Then again, I know that more recent neolithic tools of, say, 6,500 years in age, were “roughed” out before being chopped down to size.

“Let’s keep it,” I say.

The flint goes into one of my husband’s large coat pockets and is forgotten for the walk, but in the car, on the way home, I ask to see it again. I hold it in my lap for the rest of the drive. It is very heavy. It is, somehow, palpably different from anything we have found before. I am not a “woo-woo” person, but I have a woo-woo moment. A prickling under the skin, if you will. Could this axe, if it is an axe, be something very, very old indeed?

I am a collector of flint tools, and not to toot my own horn, but I am good at spotting them. Or at least, as in this case, I am good at training my close family to spot them and thereby snatch all glory from me.

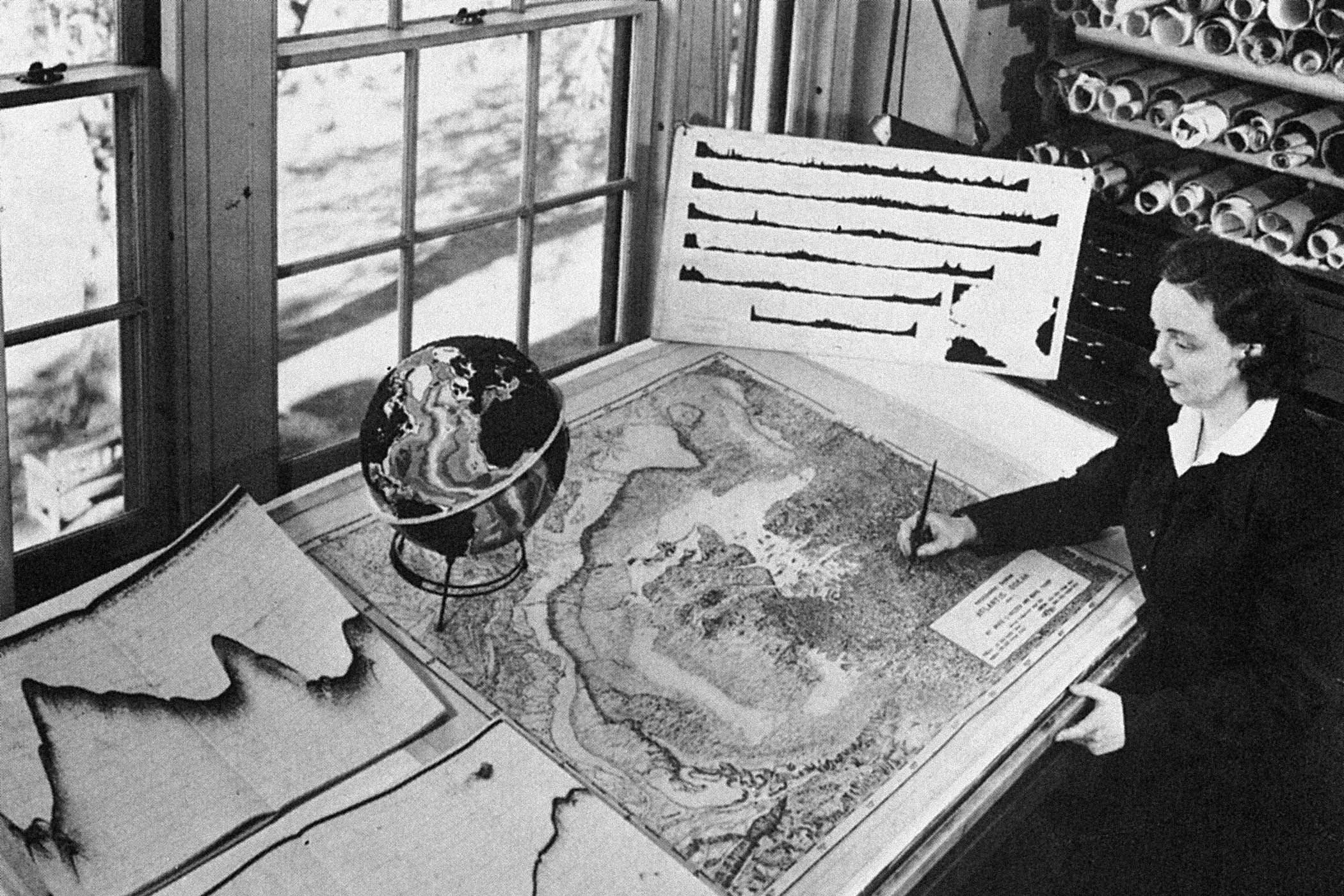

The hand axe found by Emily H Wilson and her family

When our planet warmed up after the last ice age, about 11,000 years ago, these islands were gradually transformed from icy tundra to temperate forest. That’s when our species, Homo sapiens, came north from mainland Europe (there was a land bridge then) to make a permanent home of the British Isles. In those first millennia, as we moved from being mesolithic hunter-gatherers to neolithic farmers, we lived on the hilltops in areas such as Dorset. The valleys were boggy places, wetter than they are today.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

On these busy hilltops, people used stone tools for thousands of years. It is not surprising that if you know what to look for, it is easy to find the tools they left behind, even in fields as full of natural scraps of flint as ours are. (By the way, we do not own any fields: I am merely claiming Dorset in a general way as my own country.)

Over the years, my family and I have found many beautiful objects. A delicate, leaf-shaped, neolithic arrowhead (with just a bit of its base missing); a stunning polished discoidal knife that may have been used for skinning large fish. A perfect polished neolithic axe. We have two display cabinets of flint tools and every one of them was dropped or lost or thrown away by a person of our species in the past 10,000 years.

Now of course I knew that before we settled these islands, other people came. Our own species made forays north, from about 35,000 years ago, always retreating when the ice returned. But long before that, other kinds of humans came to these islands: more ancient and more mysterious types of hominins, about whom we still know fairly little.

Those archaic humans, during what is called the palaeolithic era, used stone tools. But I knew that their tools were only found deep in quarries or caves, or perhaps they might occasionally be coughed up by a river or the sea. Amateur flint hunters like me were not going to find them just sitting about on hilltops in Dorset. Or that’s what I had always thought.

Normally, when I find what I think is an interesting ancient tool, I message a man called Nick Hando on Instagram. He is based in the Midlands and has always been very kind in helping me identify things, although we don’t know each other beyond those interactions. Now I send him pictures of the maybe-axe.

He immediately types back: “Palaeolithic hand axe with a broken tip. A bit rough but unmistakable. Now go back and look for the missing piece. It will be there. ps That’s an important find. Check the area VERY thoroughly.”

The palaeolithic is divided into chunks, and the lower palaeolithic is the oldest bit.

I am immediately heavy with a new sense of responsibility for the axe. It is wrapped in a shrunken jumper and hidden in a drawer.

That afternoon, my husband and I return to the hill. We stand in a field that is essentially a sea of flint rubble with a bit of soil in it. How can crops even grow here? We cannot see how we will ever find the tip.

Later in the day, I tell Hando that I will have the flint formally identified first thing in the morning.

A Homo heidelbergensis skull from Spain

It turns out, though, that having an old lump of dusty rock identified is not as straightforward as you might think. Our local museum tells me they no longer do identifications. They point me to the local finds officer.

Thanks to the Portable Antiquities Scheme, we have a finds officer in Dorset dedicated to recording finds (be they stone or gold or anything else) discovered by members of the public. I email but get an automated response; I imagine the officer’s inbox is stuffed to bursting. I should just be patient, but I am not patient.

A week later, Hando messages me to ask how the flint identification is going.

“No luck so far,” I say.

We speak, for the first time, on the phone. I had always assumed, from his expertise, that he was an archaeologist, but he is a university librarian. He used to hunt for fossils in his home in southern England, but when he moved north to Leicestershire, he began to spot flints in the lush fields around his home.

He did not just wander around on dog walks, picking up tools at random and putting them in his pocket, as I always have. Instead, he took an academic approach to the flints he found. His local village was not meant to have any prehistoric settlements, but with a local archaeologist, Hando proved that to be false. He gave his village an ancient history it didn’t know it had.

Learned as he is, though, he is not an archaeologist; I should get the flint formally identified. He points me to two Facebook groups that he says are heavily populated with flint experts: Stone Age Finds, and Flint Finds of History. I join both groups, and after being allowed in, I spend quite a long time photographing and videoing the mystery axe. I post the images to both Facebook groups. “Congratulations,” says my youngest son. “You have found a new way to waste time on your phone.”

Comments start to come in about my axe. People think it’s a rough-out of a neolithic axe. That woo-woo moment, that prickling under the skin, was just a fantasy, and nothing more.

Twenty four hours later, everything shifts the other way. A man named Nick Murphy leaves a detailed comment on Flint Finds of History and he does not think the axe is a neolithic rough-out.

“Wowzer,” he begins. “A Portland chert lower palaeolithic hand axe … the ‘holy grail’ to a collector like me.” He goes on, in convincing detail, to explain why he thinks it’s that age. Murphy, I quickly learn, is an acknowledged expert in the group.

I am buoyed up by his confidence in the age of the flint. But on the other hand, no one has handled the axe in real life outside our immediate family. To be absolutely sure about it, I need an archaeologist to hold it, and not just any archaeologist. I need an expert in the lower palaeolithic.

I decide to go right to the top.

The curator of the lower palaeolithic at the British Museum is a man called Prof Nick Ashton. (Why is everyone who hunts flints, apart from me, called Nick?)

Ashton has dug at every major palaeolithic site in the UK, as well as overseeing the museum’s vast collection of ancient stone tools. He was on David Attenborough’s mammoth graveyard show. He is the real deal, and then some.

I email him a picture of the axe not knowing that he is abroad on holiday. He quickly responds, however, and we arrange to meet when he is back in the UK.

My excitement levels move up to defcon 15.

On a beautiful spring morning in early May, I report, rather nervously, to the British Museum’s offshoot base in east London. In two large, nondescript buildings in Shoreditch are held the many thousands of ancient stone tools owned by the museum but not actually on display. This is where Ashton works.

England’s forests then were home to straight-tusked elephants, rhinos, lions and bison

England’s forests then were home to straight-tusked elephants, rhinos, lions and bison

We sit in his office, and I unwrap the axe from its cocoon in my old shrunken jumper, and hand it to him.

He is a quietly spoken, unshowy man, and he handles the stone carefully. “It has all the hallmarks of a really big hand axe,” he says, turning it over and around. “It’s a shame it’s so patinated… it would originally have had a much longer tip.”

I explain it was found on a flat plain on top of a chalk hill. “It’s unusual in terms of its location,” he says, “but I would have little doubt that this is not neolithic, but palaeolithic, and I think the size of it is interesting because we’ve had a series of ice ages and periods between the ice ages, and there’s one particular period that we call ‘stage nine’, which dates to about 300,000 years ago. And there’s actually a recent paper on giant hand axes from this period.” (A post-doc colleague of the professor’s later gives us the same estimate for the flint’s age.)

I think we can now safely say that my axe is roughly 300,000 years old. It is lower palaeolithic, as Hando immediately guessed. The last hands to touch it, before my husband picked it up, were not even of our species, since our species did not arrive here for another quarter of a million years. In the days when modern humans were only just emerging, somewhere in Africa, other kinds of humans walked Dorset’s hills and one of them abandoned or lost this axe. And now it sits, heavy, on Ashton’s desk.

People had suggested to me that Homo heidelbergensis, a type of early human, might have made it, but I knew that trying to identify and separate the different human species from this “messy middle” period of human evolution is complicated.

“It’s probably safer to say ‘early Neanderthal’,” says the professor.

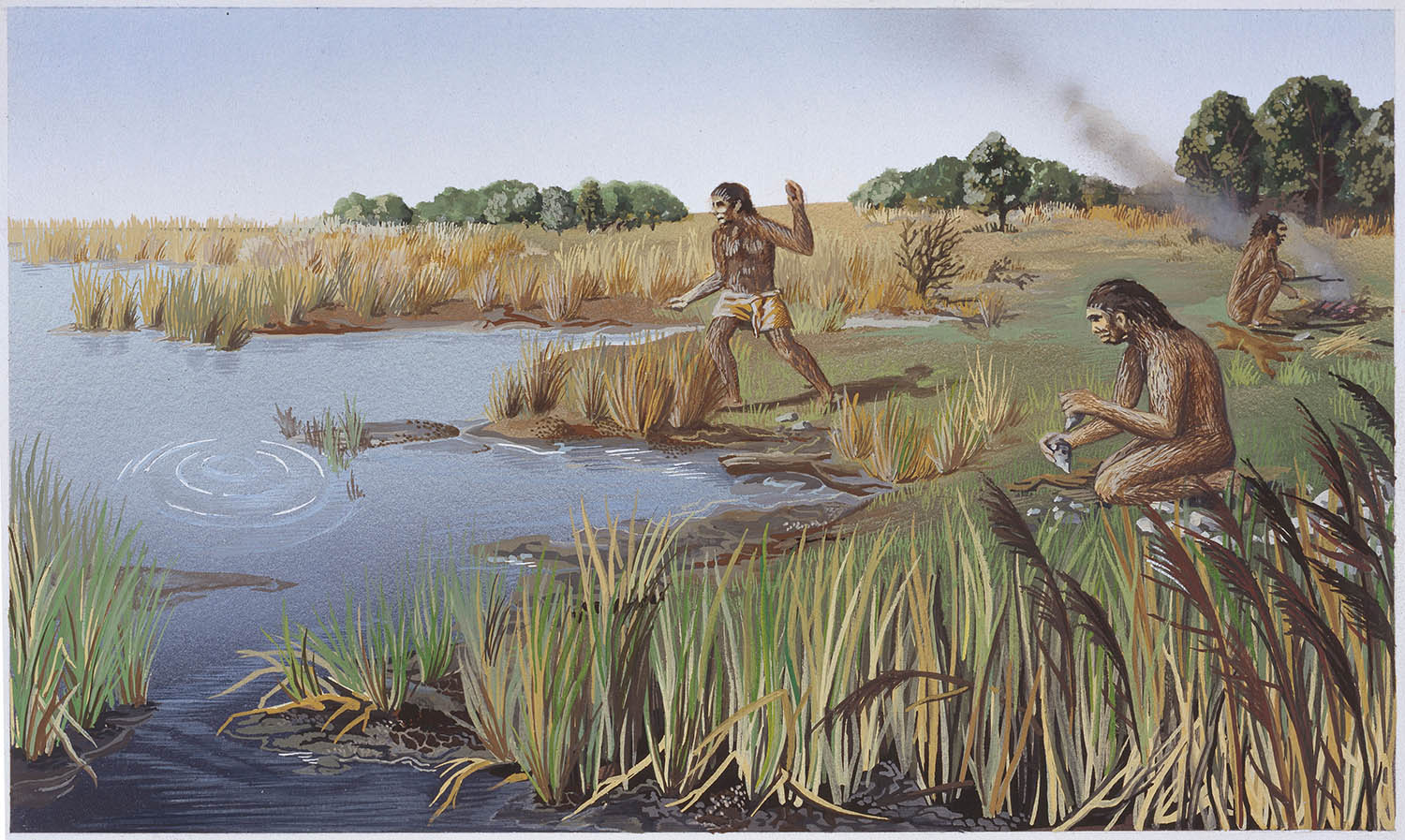

So what do we know about them? “They’re hunter-gatherers, efficient hunters,” says Ashton. “We know from sites in Germany that they had two-metre-long spears. We know from cut marks on bones they were very efficient butchers.”

They were beginning to control the use of fire, he adds. They removed hides from animals, to use the leather for reasons as yet unknown.

England, in those days, was not so different in climate from England today, but in other ways it was vastly different, its forests home to straight-tusked elephants, rhinos, lions and bison, as well as the wild horses and deer these early Neanderthals liked to feast upon.

An illustration of hominins using stone tools

As to what my axe was used for, “generally speaking, hand axes are thought to be general-purpose butchery knives,” says the professor.

There’s a twist though. With these giant hand axes – which mine does appear to qualify as – sometimes they were “designed beyond their function”, he says. After all, they did not need to be so big and symmetrical to do the job. “You get the impression there is something else going on,” he says.

“Do you mean that they might be sacred objects?” I ask.

“We tend to be very reluctant to say so,” he says, “but I’m sure they held meaning beyond everyday utility.”

So how rare is it to find an axe like this just sitting in a field? Ashton says that since the Portable Antiquities Scheme was introduced at the turn of the millennium, more and more palaeolithic surface finds like mine have been found by members of the public out walking.

My axe is not a first then, although it may be a first for our part of Dorset. The professor and I look through some old field surveys, but they do not include the area where I live, so the question of whether this is the oldest human-worked tool ever found in the hills around my home must remain an open one.

Ashton says that he is not annoyed by amateur flint hunters – quite the reverse. After all, it was a member of the public who picked up a 500,000-year-old axe on a beach in Norfolk, leading to the discovery of the extraordinary palaeolithic site at Happisburgh. Human footprints were later found there that may be up to a million years old.

I leave, clutching the cocooned axe to my chest. Not only is this axe very old, it is also, possibly, a glimpse into the minds of one of our long-lost ancestors.

As Hando later puts it to me, where this particular axe was found is also significant. It tells us that “the upland ridges were an important location for early man as routes across the landscape and places of habitation”, he says.

The next day I return to the site of the find. The crop has come in; we will not find the tip until the seasons have turned and the field has been scraped bare again. If we do ever find it, in this sea of flint rubble.

With or without its tip, though, the find will be recorded, in good time. I will be patient now. Meanwhile, what a thing to know that the history of my home village goes back not just 10,000 years, as I had thought, but 300,000 years, to a time when we still had lions and elephants roaming these beautiful chalk hills.

Meet the ancestors

The hominins are a taxonomic tribe that comprises two genera – Homo, the humans, and Pan, chimpanzees. It includes all the extinct human species from which Homo sapiens evolved. They are part of the broader designation hominids, which refers to modern and extinct humans and all the other great apes, including gorillas and orangutans.

Hominins first appeared around 6m years ago, during the Miocene epoch. Around this time, the fossil record shows humans diverging from all the other apes.

The subsequent early Neanderthal species date back to fossils from about 430,000 years ago. These early humans maintained and possibly created fire, and are believed to have fashioned and worn blankets and ponchos.

Early Neanderthals lived in hunter-gatherer societies, killing big game such as rhinoceroses and mammoths, as well as eating plants and mushrooms.

The earliest hand axe discovered in Britain to date is more than 500,000 years old.

Emily H Wilson is a former editor of New Scientist magazine and the author of The Sumerians, a trilogy of novels set in ancient Mesopotamia

Photographs by AlamyGetty