Portrait by Suki Dhanda for The Observer

The Syrian film-maker Hasan Kattan knows that taking a decision to leave your homeland to see the world is a kind of luxury. Like the many others who have, instead, been forced out, he understands that making a choice would have been very different. A strong sense of exile means he longs for the sights and smells of Aleppo – for the everyday life he once knew.

“Behind the words ‘displacement’ and ‘refugee’, there’s always a huge story. If people ask me why I decided to come to Britain, I’ll tell them there was no ‘decision’. I am still stuck in that moment,” says Kattan, who worked on the Oscar-nominated short documentary Last Men in Aleppo (2017).

“Maybe because I’m a film-maker, it is all constantly rolling through my brain, even with everything else happening around me now in Britain. We had all accepted living and dying under siege in Aleppo, until we were forced out.”

Kattan, 33, began his career as a citizen journalist, filming in the ancient streets of the city he loves. He later became a cinematographer on The White Helmets, which won the best short documentary Academy Award in 2017 for its depiction of the rescue efforts of the Syrian civil defence force.

He now lives in Slough, Berkshire, with his wife, Rama, also from Aleppo, and their two children, Kamelia, six, and his eight-year-old son, Thaer, which means “rebel” in Arabic.

The hand held out to him in Britain by the transformative charity Counterpoints Arts has been a lifeline, he says, not just professionally but emotionally. It helped him cope with acutely painful memories and with the beleaguered state of seeking asylum, especially in the year and three months before his family were able to join him.

The charity, set up in 2012, supports, produces and promotes creative work made by and about migrants and refugees, allowing their stories to alter perceptions of international displacement. This year, The Observer has made Counterpoints the beneficiary of our annual Christmas appeal.

“They build a network to support you. You are alone, but they are standing with you,” says Kattan. “You just want to be accepted and dealt with as a human being. Not as a number, not as dangerous – just as one human to another.”

Counterpoints offers advice to individual artists, but also runs significant arts programmes, including its film arm, Counterpoints Productions, the Platforma festival, which presents work by, with and about refugees, and Refugee Week – now in its 27th year and the world’s largest festival to celebrate the creative contribution of refugees.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The charity’s work is concentrated on areas of high migration and low arts investment, and its access schemes include a pioneering initiative, PopChange, which sets up influential creative networks among migrants and came along just in time for Kattan. “It was a unique experience that I needed and it healed me a lot,” he recalls.

“I was invited to a PopChange retreat. I didn’t know what a retreat was then, but I had two or three days of talking to lovely people who really understood. It was heaven, really, being with about 50 people from different backgrounds, all talking about the big issues: immigration, social change and climate change.”

Kattan’s next film, Allies in Exile, is being made with a grant from the new Displacement Film Fund, launched this year by the actor Cate Blanchett, and will follow the story of the asylum seekers housed in British hotels.

“Inside those hotels, it was destructive and harsh. The system destroys you from inside because you don’t know how long you will spend in it. It was a terrible time,” says Kattan.

His British film project was made possible by the connections established through Counterpoints. He now offers assistance to other migrants, doing everything he can to help them: “I can’t say how much I am trying to pay Counterpoints back. I don’t know how I would have survived without them.”

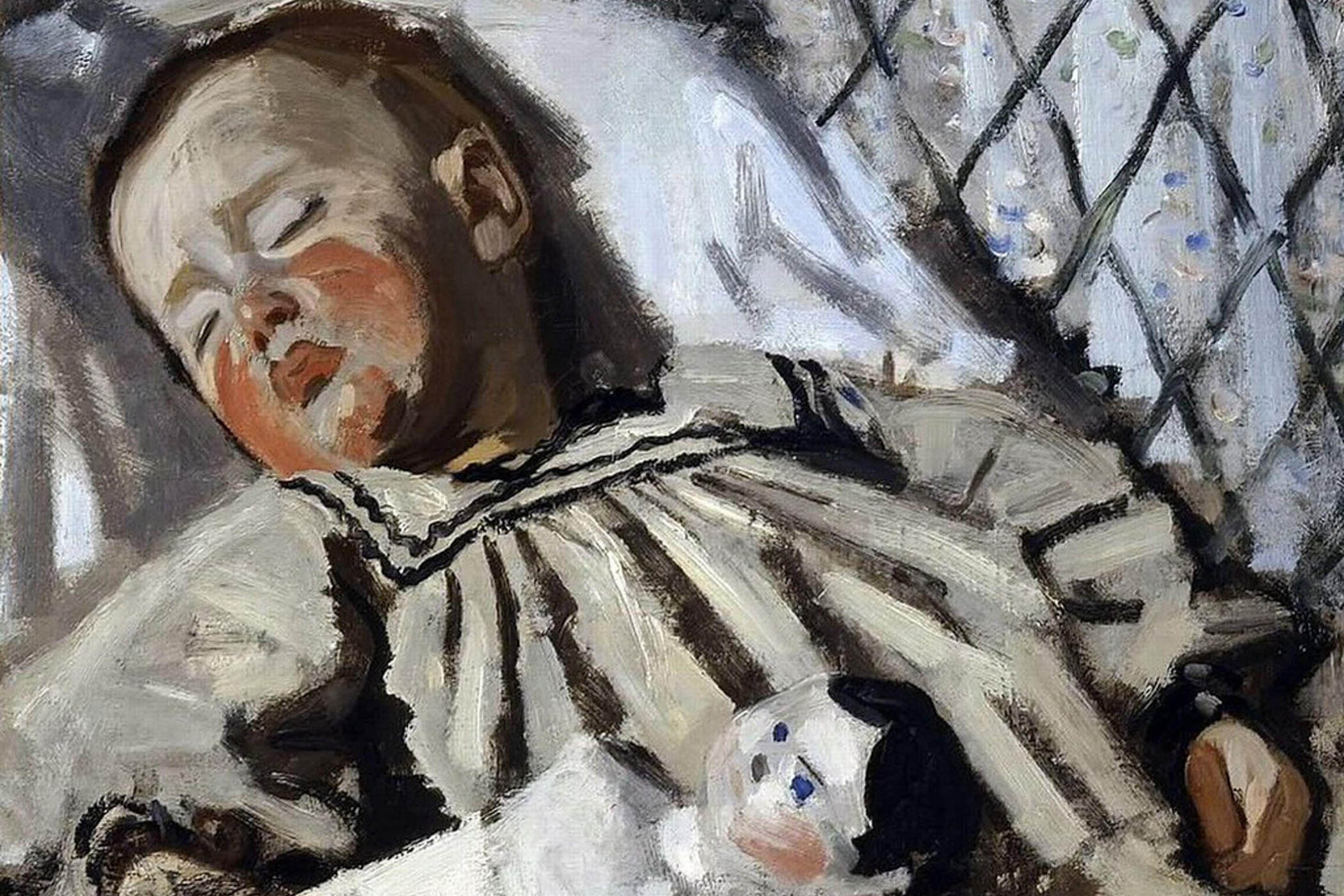

Parents and children in Aleppo, northern Syria, the home city of film-maker Hasan Kattan

Kattan was born in Aleppo in 1992, one of six siblings. His father worked in a clothing factory while his mother ran the home and educated her children.“It was a normal family, but I knew nothing of life outside Aleppo because that was life under [Bashar al-]Assad’s dictatorship. There was no real social activity. I studied law at university in the city and had a lot of dreams of changing things.

“I was insanely passionate about the law and could listen to a professor talking for hours. I had unlimited belief in it and planned to become a judge. But I didn’t get to graduate.”

As a student, Kattan first came up against the repressive regime when he suggested his university should set up a model parliament to run the campus like a small country, as a way of practising for a democratic future. “But I was told to shut my mouth,” he says. “I needed to get the approval of the ruling Ba’ath party.”

Kattan’s initial attempt to film political unrest in the wake of the Arab spring was an equally rude awakening: “Someone asked if anyone could film a demonstration. But I was nearly finished by doing it because the Mukhabarat, the security police, saw me and surrounded me.”

Luckily, a friend grabbed the camera and ran, so there was no proof. “I could have been ‘disappeared’ for that,” Kattan says. “But then everything I am now was reborn in the revolution in 2011.”

Even as he works on the new film, he is haunted by the question of whether to go back to Syria to build a new future, now Assad has been ousted. “But do I get to choose what I want? That struggle in Aleppo was an exhausting alternative life, but I want to return. My new film explains how telling the story has helped me to get through it all.”

To donate to Counterpoints, please click here.

Other pictures by Fadi Al-Halabi