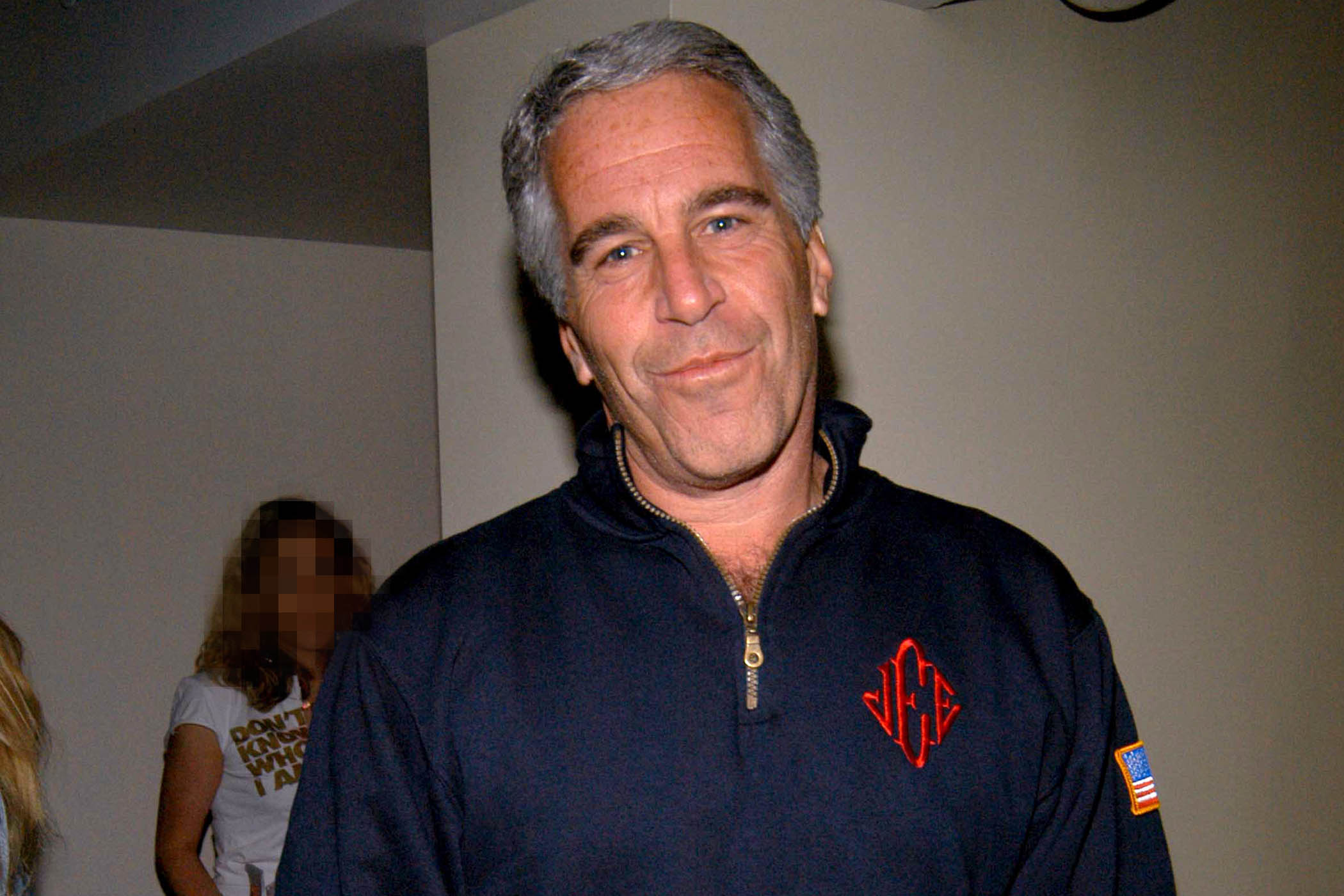

Open up TikTok today and you might see a video of Jeffrey Epstein dancing in the snow, dressed in a navy blue, quarter-zip sweater that features heavily in the newly released Epstein files. Scroll, and you might see him hands on hips, in the same sweater, gyrating to the sound of Sir Mix-A-Lot’s Baby Got Back. Then you might see him, again in the same sweater, sitting in a big leather chair, telling his audience: “The worst thing she can say is no.”

None of these videos is real. They are AI-generated memes posted on “tryunredacted”, a new account on TikTok that posts daily clips of Epstein dancing. It has almost 50,000 followers and sells a version of Epstein’s sweater for $54.99; in September, a similar sweater sold for $11,000 at auction in Miami. It produces a drop in the ocean of Epstein memes.

This week, the Epstein files have returned to public view, flooding social media as content.

Screenshots of Epstein’s emails are posted across X, Bluesky and Instagram with punchlines. His name trends next to jokes, reaction GIFs and ironic captions. These reactions come from high-profile non-profit groups such as the Lincoln Project, set up by a group of anti-Trump Republicans, which shared a Sesame Street-style video in which the lyrics of Kendrick Lamar’s Not Like Us are replaced with references to Epstein. “Spill the tea on your besties from the Lolita Express,” a puppet sings to a felt version of Trump. It also shared a photo of Brett Ratner, the director of the Melania documentary, with Epstein, both of them hugging women: “This guy had two terrible pictures come out this weekend.”

Conspiracy theorists are using the files to reignite the “pizzagate” furore, a made-up story about high-profile politicians involved in the widespread satanic abuse of children. “Epstein documents mentioned pizza 900 times,” one tweet reads. “THERE ARE NO COINCIDENCES.”

Something chilling is happening here: Epstein’s grotesque, extensive sexual abuse network is being processed by the internet as a meme.

This is not an accident; to become a meme is to become unreal. Memes flatten reality into irony and disintegrate consequence. When Epstein becomes a punchline, the crimes attached to him and his powerful friends – rape, trafficking, the systematic abuse of girls and young women – are abstracted. The bodies of his victims, abused and exploited, photographed while they were abused, discussed casually in emails by powerful men, are transformed into something laughable. Irony creates distance from horror.

And distance breeds popularity. AI-generated videos of Epstein dancing are proliferating across TikTok. One AI-generated TikTok video of him in the sweater, gyrating and miming slapping a woman, has received more than 100,000 likes. Another video shows Epstein walking down a red carpet, making eye contact with Sean “Diddy” Combs, the convicted sexual abuser, that has garnered 40,000 likes. A video of an Epstein rave has 62,000 likes. A “looksmaxxing” account even imagines how Epstein might look if he “locked in” – incel-coded language for maximizing sexual appeal – revealing the crossover between Epstein meme culture and the manosphere.

Related articles:

But this phenomenon extends far beyond any single subculture. On TikTok alone, #JeffreyEpstein is linked to more than 64,000 videos, many of them memes. And it’s not only AI: the real material cuts through too. One email has become a popular object of online analysis and commentary. In it, Epstein asks a mystery correspondent “are u ok” and goes on: “I loved the torture video.”

The meme-ification of the Epstein files seems to function as a pressure-release valve: it allows public engagement without moral reckoning. You don’t have to sit with horror if you’re laughing. You don’t have to ask who enabled him, protected him, benefited from his silence or joined in on his abuse when the story itself becomes a joke.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

This dynamic mirrors a broader political logic. It is a classic Trumpian move, perfected by the present govern-by-meme administration: overwhelm the public with volume and performance until that internet-culture tone replaces truth as the primary signal. The sheer amount of information released – thousands of pages, names, emails, fragments – exacerbates this shift. When everything is shocking, the shock dissipates and nothing is actionable. When every revelation arrives wrapped in irony, accountability dissolves.

The victims dissolve too. Back in July, Arick Fudali, a lawyer representing several of Epstein’s victims, warned that memes “undermined” these women. “It’s enough,” he said, “let these victims rest. At least acknowledge that they’re the ones that are suffering here.” Their actual, living bodies have already been circulated among abusers. Now they circulate online – their faces covered in black, bodies vulnerable, sometimes in minimal clothing or naked – as internet fodder.

Emma Connolly, a social media researcher at University College London, says memes of Epstein’s abuse “obscure the severity and reality of the crimes… taking the focus away from his victims”. According to Connolly, this is a larger consequence of meme culture, which “spreads quickly and normalises harmful topics by presenting them in humorous and engaging ways”.

Some images shared tens of thousands of times are impossible to forget: a woman’s foot inscribed with a quotation from Lolita; Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor pressing his hands leeringly into a young woman’s body. Another image is even more disturbing: a child with her hands taped and cuffed, so horrifying it barely registers as real. It isn’t real it’s AI – but meme-ification means the difference between real and generated is fatally blurred. Why not dismiss the real as we dismiss the artificial?

The circulation and meme-ification of such images produce a visual salaciousness that crowds out what remains unseen and unshared. This aesthetic of irony conceals insidious truths. The domestic, everyday realities of Epstein’s crimes are obscured by this torrent of images, even as that shock resurfaces in unforgettable fragments, such as one of Epstein’s many disturbing emails, dated 2013, that reads: “I like buying you school books.”

The Epstein files document a system: one in which wealth insulated abuse, institutions failed children and powerful men relied on the expectation that they were untouchable. Don’t fall for the trap: the algorithm is trying to destabilise the truth of this system. Laughing can help us process the horribly traumatic, it’s true, but in this case it further exploits the victims of Epstein and his friends.

What is required instead is sustained attention and moral clarity, an insistence on seeing these crimes as systemic and unresolved. Without that, the noise does exactly what it was always designed to do – protect power, erase victims and ensure that nothing truly changes.

Photograph by Neil Rasmus/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images