Hundreds of children were kidnapped by the state and placed in orphanages during the Syrian civil war. One charity, SOS International, helped disappear them, colluding with military intelligence to break their parents. SOS was able to keep their complicity a secret – until the regime fell

The first time Abdulrahman Ghbeis held his son, Mohammed was already three years old.

The dark-eyed, black-haired boy was stolen by Syrian intelligence from an incubator in a Damascus hospital just days after his birth.

For the next three years, he lived in the care of strangers. In an international orphanage on the city’s outskirts, the infant was bottle-fed, surrounded by children he didn’t know, never knowing his mother or the warmth of her arms.

But day and night, in the darkness of her cell, his mother Iman whispered his name. She had never held him, never kissed him. Every night, silence pressed in. Where is he? Is he alive?

Thousands of children disappeared during Syria’s 13-year civil war. But Mohammed is one of hundreds not taken by bombs, but by a quiet, bureaucratic violence, carried out through files, signatures and sealed envelopes. As his mother and six other members of his family were arrested, he was left in an incubator and then spirited away.

Mohammed’s story can now be told as a result of a nine-month investigation by a consortium of Syrian and international journalists coordinated by investigative newsroom Lighthouse Reports. Their findings show how President Bashar al-Assad’s regime weaponised the children of political detainees to break their parents – and how the orphanages meant to protect the children became instruments of that abuse.

The investigation involved more than 100 interviews with families, orphanage employees, government officials, whistleblowers, activists, lawyers and other witnesses, and obtained hundreds of classified documents from Syrian intelligence. It uncovered a coordinated system of child abduction.

Many of these children were hidden for years, their identities buried beneath false names and forged documents. Others were quietly separated from siblings, adopted out, or secretly deported

Our database has identified more than 300 children of detainees –including newborns – who were placed in four orphanages across the Syrian capital. Their parents had disappeared into prisons; the children, labelled “security cases”, were used as leverage in prisoner exchanges for regime soldiers.

Many of these children were hidden for years, their identities buried beneath false names and forged documents. Others were quietly separated from siblings, adopted out, or secretly deported. Some children were handed to the military. With records often chaotic or incomplete, the true number is almost certainly higher.

This system wasn’t upheld by the Syrian regime alone. SOS Children’s Villages International – the world’s largest non-profit for children without parental care, headquartered in Austria – was complicit. Behind the gates of SOS-run facilities, children suffered emotional, physical and sexual abuse, including invasive virginity tests.

We have discovered that for years, the Austria-based leadership knew about the unlawful transfers and abuse – and stayed silent. They didn’t think anyone would ever find out. Then, in December 2024, the regime fell.

In spring 2011, Syria’s streets filled with chants for freedom, carrying on the winds of the Arab Spring. In Daraa, the arrest of teenagers for anti-government graffiti sparked protests against ruler Bashar al-Assad. The regime responded with brutal crackdowns. Men, women and children were swept up in midnight raids, dragged from homes, or seized at checkpoints. Prisons filled with protesters, activists and bystanders.

By autumn, Syria was at war.

Anti-government forces took control of eastern Ghouta, near the capital, Damascus, and its towns and villages were soon put under siege by the regime. Inspired by the protests, a young man, Abdulrahman, joined the Red Crescent aid organisation— not just to help, but as a means of quiet resistance. He drove an ambulance and smuggled medical supplies. Government hospitals were deadly traps for protesters, so they turned basements into makeshift clinics. “We treated everyone – soldiers, rebels, civilians,” he said. “That’s why the regime targeted us.”

Anyone who aided the wounded risked being shot, beaten or disappeared. When in 2013 a sarin attack killed 1,400 in the city of Douma, Abdulrahman gathered evidence.

The siege worsened, aid collapsed, there was no electricity, water or food and with no safe place to give birth, in the spring of 2015, Abdulrahman sent his pregnant wife, Iman, to Al-Tall on the outskirts of Damascus, where they both had family. His sister, Omama, and her family also joined her – but Abdulrahman couldn’t risk it. He’d be arrested on sight.

Soon, he received a call from his mother that he would never forget. “Congratulations, you have Mohammed.”

He posted his newborn son’s photo online with a caption: “God willing, he’ll grow up to protect Syria and live in freedom.”

Later, he blamed himself for his son’s disappearance. “It was my fault.”

Baby Mohammed entered the world by caesarean – weak, jaundiced, struggling to breathe. Diagnosed with severe hypoglycaemia, he was placed in an incubator. “Iman was in pain, desperate to know if he was OK,” Omama recalls. “I told her: ‘Mohammed will be in your arms in a couple of days.’”

But then the arrests came.

Four days after Mohammed was born, on 4 August 2015, Omama, her husband, and their two daughters were arrested at a makeshift checkpoint near Damascus. “It was clear – they were waiting for us,” she said.

Two days later, they took Iman too, still recovering from her C-section.

Eight members of their family ended up behind bars, targeted because the regime had labelled Abdulrahman, the ambulance worker, a terrorist.

That night, Abdulrahman texted his wife in panic: “What happened to you? What happened to Mohammed?”

No reply.

He called his sister Omama – nothing.

He called everywhere for help. No one knew anything, or maybe they were just too afraid. He was being monitored, his Facebook, his phone calls. “I was too known, too involved. The regime saw people like me – who stayed to help – as the real threat.”

Days later, the Red Crescent confirmed to Abdulrahman that baby Mohammed was alone in the hospital incubator in Jobar, a village on the outskirts of Damascus. But when a member of the Red Crescent, joined by the local mayor, went to the hospital to check, staff warned them: “Leave now and never ask again, or you’ll disappear.”

Abdulrahman, desperately searching for his son, found the number of a hospital security officer tied to Syrian intelligence. He messaged, offering money for the return of his son.

The officer never replied.

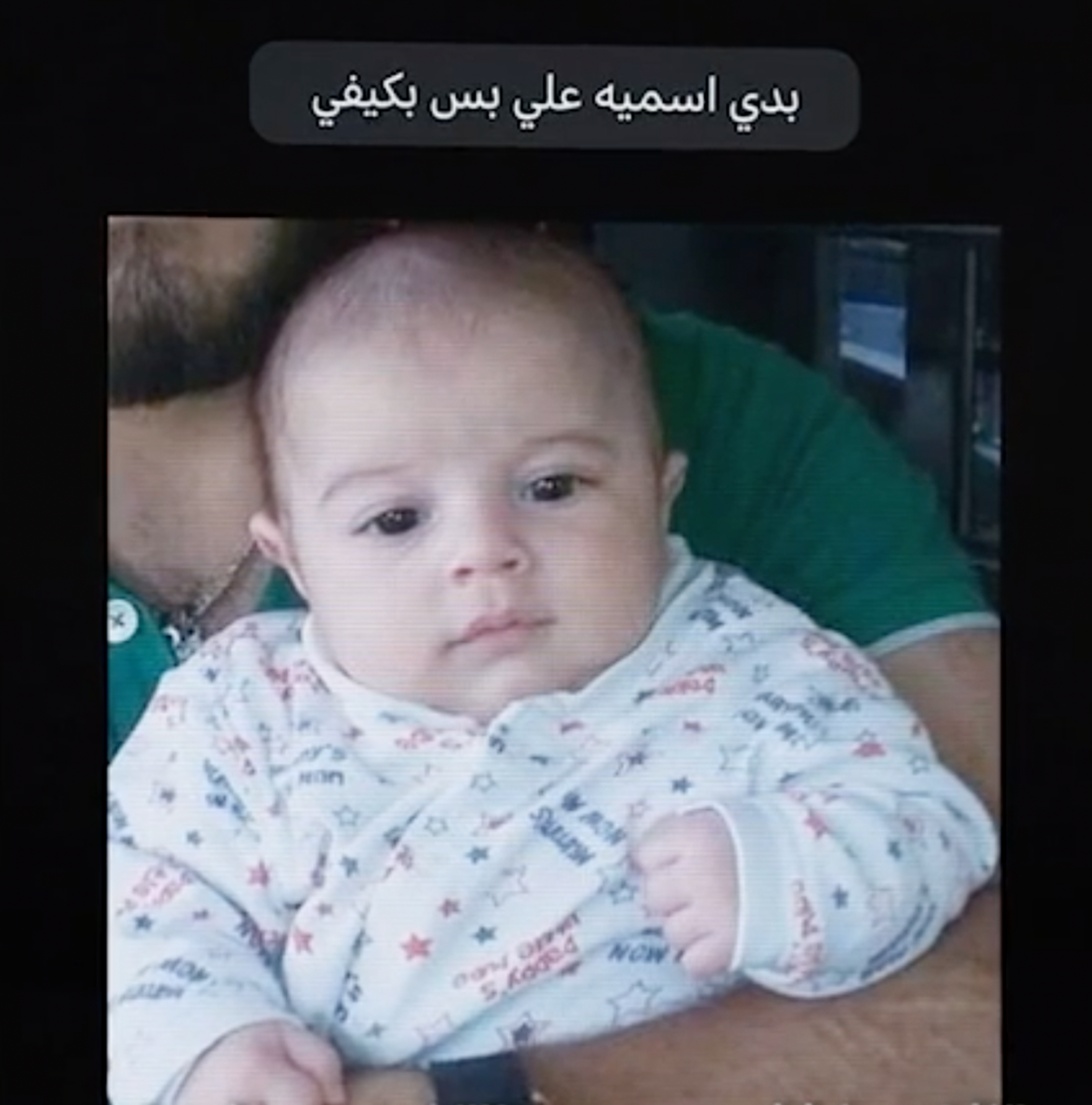

Instead, the officer posted a photo in his WhatsApp status of baby Mohammed on his lap: “I’ve named him Ali.”

The photo of baby Mohammed posted on WhatsApp by the hospital security officer.

Leaked Air Force Intelligence documents and messages exchanged with Abdulrahman reveal what happened next.

On August 15, an intelligence officer sent him a Facebook message—a photo of baby Mohammad, and an impossible demand. “If you want your family, give us prisoners.”

As was often the case: the regime was demanding the release of government fighters held by the rebels.

“I froze,” Abdulrahman said. “For days I stared at it, terrified, consumed by guilt. Someone had taken him.

“If he’d been with me, he’d have been safe. They stole his freedom—his childhood. The chance to be held, breastfed, to know his mother’s scent. That bond shapes a life. They took it all.”

Weeks turned to months and the messages from the regime continued – on Facebook, Skype, WhatsApp.

“One man demanded a prisoner swap: ‘Three for one’.” Abdulrahman asked for the names of prisoners that the regime wanted, and pushed for proof of life of his family – his wife, his sister, his son—knowing he had no real leverage.

Abdulrahman tried to buy time, even faking his own death in a Facebook post. “If they thought I was gone, maybe they’d let my family go.”

It didn’t work. The demands for prisoners kept growing. He nearly turned himself in, but friends worked in shifts to make sure he stayed at home. “I blamed myself. [My wife] Iman had begged so many times to leave for Turkey. I wish I’d listened. I wish they’d taken me instead.”

He imagined Iman bleeding to death after her-C-section, and their only child, crying in the dark alone.

He reached out to anyone released. No one had seen her. Then a rumor claimed they were dead. “I collapsed—but felt relief. At least they weren’t being tortured anymore.”

My wife had begged so many times to leave for Turkey. I wish I’d listened. I wish they’d taken me instead.

Abdulrahman Ghbeis

By now, it had been several months since Mohammed had been born, several months since he and his mother had been abducted.

Leaked documents show airforce intelligence officials discussing over several months what to do with newborn Mohammad. In August 2015, officials proposed detaining him and his cousins “to benefit from them” in a prisoner exchange. By early October, orders directed him to be placed in an orphanage.

“Is it reasonable for the child to stay with the mother?” one official asked. A week later, the reply: “he should remain in the hospital, then be handed to his grandfather – under supervision – as part of negotiations led by Unit 17” – a shadowy security branch that secretly handled hostage deals for the Syrian investigation branch.

The next day, another order came: Mohammed was to be moved to “a secure hospital under supervision.”

On 10 November 2015, intelligence informed Al Mabarrah, a Damascus orphanage, that they would deliver Mohammed into their care. A week later, the director signed a letter confirming his arrival.

He was three months old.

When Assad’s rule collapsed on 8 December 2024, the gates of Syria’s secret prisons, airbases and intelligence branches swung open. Grieving families poured in, desperate for answers.

Those who’d waited years for news of their children taken by the regime began to search, often on their hands and knees, tracing names in fading ink, combing through boxes of IDs and passports, hoping to find a familiar face or name. Some turned to orphanages, clutching photos. A few were shown archives of documents, and scanned them for a resemblance – eyes, a hairline. But how would they look today? Others were turned away at the door.

Inside these buildings, answers sat unsorted in silence: banker boxes stacked high, filled with documents tying state intelligence to the transfer of detainees’ children into and out of the orphanages. Stacks of brown envelopes marked “top secret” held the truth in plain sight: hundreds of memos from top security officials listing women and children by name, each stamped: “Decision: Approved.”

I flew to Damascus. In the first week alone after the fall of the regime, I visited prisons, air bases and four intelligence branches including air force intelligence, and photographed nearly 7,000 documents at these sites. Among them were letters from air force intelligence with children’s names, followed by instructions to keep them confidential.

These weren’t random arrests. Documents collected over multiple trips I made to the Ministry of Social Affairs, orphanages, and from an air force intelligence leak revealed a pattern: detainees and their children had been held as bargaining chips, to be traded in prisoner exchanges.

Since December, a “special investigation team” inside the Ministry of Social Affairs – responsible for the orphanages – told me they’ve been sorting through the files. So far, close to 320 names of children forcibly separated from their parents and sent to orphanages have surfaced. The numbers are incomplete – some orphanages hid records to cover up their involvement. The new head of Syria's orphanages told me “everything they have” will be handed over to “the relevant security apparatus”, now run by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, the Islamist group that leads the new government and that toppled dictator Al-Assad.

But what I was hunting for was more than the names of the disappeared. I wanted to know the extent of western complicity in this system of torture

But what I was hunting for was more than the names of the disappeared. I wanted to know the extent of western complicity in this system of torture. In December, days after the regime fell, I had seen an Instagram post by a charity called SOS. It is a well-known organisation, operating orphanages worldwide since 1949 and in Syria since 1975, and which has – over the past 12 years of Assad’s regime – been supported with €29,592,000 from international donors and partners.

Their mission globally is simple: provide stability for children who had lost their parents – or whose parents could no longer care for them.

The post said that during the civil war, the regime had placed children in their care, an extraordinary admission. “They received support in line with our principles of safety and wellbeing,” they said .

The dilemma is familiar: should international charities work in places where they must cooperate with oppressive regimes – risking complicity – or stay away, perhaps leaving those in need behind?

After seeing that Instagram post, I wanted to investigate exactly what bargain SOS had made – with itself, with the regime – while it operated in Syria during the civil war. How could a large international non-profit argue that it was operating within the parameters of international child protection laws and in the best interests of the children while simultaneously keeping parents and their children apart at the demands of a dictator?

Government documents and shell casings litter an abandoned Syrian Air Force intelligence base.

During a trip to Damascus in December, I went to a quiet office tucked away across the city, and met Samer Khaddam, the national director of SOS Children’s Villages Syria. I asked him how many children taken from their parents by the regime had the charity accepted.

“It’s not many, maybe 30… 35… not many,” Khaddam said, claiming that SOS had no choice, and urging me to instead focus on SOS’s “good work”. He handed me a pamphlet titled “We work to keep families together.”

But for years, families have accused SOS of withholding their children. When relatives did manage to trace them to orphanages, intelligence officials often refused to give their children back. When some mothers freed from prison went in search of their children, they were detained again for years.

After the regime collapsed, a Syrian man posted a video accusing SOS of helping the regime disappear his sister’s children. SOS scrambled to respond. At first they acknowledged receiving 40 children who had been “unnecessarily separated from their families” since 2013. By February the number had risen to 139. Most of them – 104 children – were “returned to authorities” SOS said, and their whereabouts remain unknown. By July, SOS said they had no idea how many children were truly affected worldwide.

Leaked documents indicate the true number could be higher. We reviewed documents of five children at SOS whose parents were in detention but who were not included in SOS’s official count.

SOS claims it stopped accepting more children of detainees in October 2018, but official records indicate that intelligence agencies continued to refer several children to SOS as late as 2022. SOS denies receiving the documents or the children.

At the detention facility, Abdulrahman’s sister, Omama, and her two girls, Layla and Layan, eight and four years old, were separated from her husband and put in a cell with 25 women. That night, Omama didn’t sleep, watching her daughters in the dark. “I was terrified they’d suffocate in their sleep.”

The next morning, blindfolded and bound, they were taken to air force intelligence – the most feared arm of Syria’s vast security network and Assad’s prized tool of loyalty and repression. The girls were questioned alone about their uncle Abdulrahman. They were fed lies, manipulated, their fear twisted into false confessions, says Omama. “They told Layla she’d seen her uncle in Damascus. ‘The one with the big beard who kissed you and tickled your belly…’ She was eight. Scared, she said yes to make the questions stop.”

Layla and Layan before they were abducted.

Days passed with relentless beatings and questions about Abdulrahman. “You’re going to stay here for ever,” one interrogator said as he beat Omama. “Your daughters will be sent to an orphanage, and you’ll never see them again. We can take them – and do whatever we want.”

Two storeys underground, they were locked in a dark, damp cell no larger than a closet. Names were forbidden. Omama was number 446. Layla was 446-1. Layan, 446-2.

In the cell next to Omama and Iman – who was still recovering from her C-section – two sisters gave birth weeks apart. Each went into labour on the cell floor and was taken to the hospital in the morning. They returned weak, hungry, and clutching their newborns. Soon after, the babies were taken from the cells to SOS Children’s Village.

The cells were packed. Almost every woman had a child, sleeping on thin blankets on the floor. Some had been there for years. “None of them ended up with the detainee’s family,” says one mother. “Some were a month old, others three years. All were taken to the orphanage.”

The SOS Children’s Village outside Damascus.

They knew when SOS had arrived to take the babies, the mother said, and when they dropped them off for visits, because they heard the mothers crying. Sometimes SOS announced themselves. Other times the mothers were told nothing.

Omama knew she needed to prepare Layla – her eldest daughter – for what was coming.

“You need to memorise your name, your family’s name. You’re going to be taken far away and you’ll need to remember who you are so one day you can find your way back.

“You’ll have to be a mother to Layan. She’s little. Take care of her.”

Layla froze. “Mum, it’s too much.”

Two days later, guards came for the girls. Omama was put into solitary confinement.

When she asked about her daughters, the guards told her that the Ministry of Social Affairs had contacted her wider family and sent the girls to them. This was a lie.

Omama’s daughters were secretly taken to Qura al-Assad, an SOS Children’s Village on the outskirts of Damascus, home to 150 children behind locked gates.

The children, many just babies, arrived at SOS under the direct supervision of different intelligence branches, including air force intelligence, military intelligence branches 227 and 235 and general intelligence directorate, branch 251, with changed names and accompanied by ministry letters claiming “unknown parentage”. In other cases, their names were not changed, and SOS knew exactly who the children were. At SOS, Layla was told to use her father’s name instead of her real surname. Her sister was called Layal by staff, instead of Layan.

When she arrived at SOS, Layan didn’t speak for more than a month.

Some children came straight from the detention facility at Mezzeh air base and Adra prison in the company of SOS staff; others were transferred from different orphanages. They were placed in apartments with a dozen other children – some abandoned, others orphans from war – under the care of a designated “mother”, part of the SOS model meant to mimic family life. But these weren’t ordinary cases. SOS said that based on available documents and records, they cannot confirm whether SOS Children's Villages staff ever transported children directly from prisons to SOS facilities.

The women's detention facility at Mezzeh airbase.

Staff knew they were children of detainees with real names and documents on file. Still, no family could reclaim them. “All movements regarding the children were directed by security forces,” said one SOS employee. “No information was shared with relatives.”

As requested by intelligence, SOS kept the children of detainees' names and presence a secret, at times separating them from other children. The staff were told not to ask questions about the children or their background and in some cases were told to use different names for them while they were in SOS care. SOS said they have no records of such incidents which they say are not common practice at SOS Children’s Villages.

SOS staff said that they were strictly instructed not to photograph the children of detainees or include them in any fundraising and promotional media. The children of detainees were banned from activities and from going to the seaside with the others, says one staff member, and staff had to request permission from intelligence for them to attend school or go for medical checkups. “There was a great deal of security around them,” recalled one SOS ‘mother’ carer.

“Most caregivers were regime loyalists,” another said. “They saw them as terrorists’ kids.” The children felt that rejection daily.

After the Assad regime fell, troves of documents revealed how SOS had quietly colluded with Syrian security forces. It was not the only international organisation that had chosen to stay and try to do good in the rubble of the civil war: many, including Islamic Relief and Save the Children, tried to provide lifesaving aid. But SOS’s presence illustrates a level of complicity with the regime unknown until now.

SOS staff knew when the children of detainees arrived because they had to report it to HQ in Austria, one employee said. Another recalls the head of the SOS Syria board, Samar Daaboul, instructing them to receive the children, and if they arrived without papers they were sent to get new documents. When a whistleblower raised concerns, Daaboul reportedly told them not to get involved. Working in collaboration with a group of journalists, in May I asked Daaboul about this: and she said she couldn’t talk about the children of detainees: “It’s not my responsibility or my role to answer any question.” Days later, SOS announced she had stepped down –officially as of 1 May 2025 – “to allow investigations to proceed without any impediment”.

Samar Daaboul says Asma al-Assad only visited SOS once and denies her father’s position had any influence on her work at SOS.

SOS admitted security forces controlled everything: where children were placed, how long they stayed, who could see them, and when – or if – they were reunited with family

In August, SOS admitted security forces controlled everything: where children were placed, how long they stayed, who could see them, and when – or if – they were reunited with family.

Across Damascus, three Syrian orphanages: Lahn al-Hayat, Dar al-Rahma and Al Mabarrah, also took in these children. Some separated siblings, their files listing false backstories – found in a park, picked up on the street – to erase the reality of what had happened: they had been taken from their families by force.

Letters exchanged between air force intelligence, the Ministry of Social Affairs, local Damascus governors, and orphanage directors lay it out:

“Please accept this child… do not disclose his identity.”

“Find a suitable orphanage... and keep their names private.”

Between 2012 and 2024, the orphanages quietly did as they were told, taking in hundreds of children of detainees, from newborns to 16-year-olds. Seventy-two children were under the age of three. At least six were born in detention.

A third of the children went to homes run by SOS.

These orphanages remained under the control of the regime and were regularly visited by the dictator’s wife, Asma al-Assad, who also toured SOS HQ in Austria in 2009. Her Syria Trust for Development partnered with SOS on projects, and the Assads were close to Daaboul – her father was a senior advisor in the president’s office and her brother was a business mogul with close ties to the state. In 2009, the then-SOS president, Helmut Kutin, met with Bashar al-Assad in Damascus.

When one manager raised concerns about Asma’s visits, HQ told her to stay quiet. “Most staff came through the palace,” said another employee.

SOS Children’s Villages – a federation with an annual income of €1.6bn, including donations from the EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), European Commission and the UN, operating in 137 countries through independent local associations – has been marred by allegations of corruption, abuse and systemic cover-ups since the organisation’s first orphanage was established in 1949.

Nearly eight decades on, hundreds of allegations of abuse have slowly surfaced across more than two dozen countries – through scattered media reports and a series of internal investigations. Despite this, the organisation has continued to grow in size and funding.

Across SOS global operations, there have been multiple allegations of widespread physical and sexual abuse, including the rape of young girls by staff – including a four-year-old mute girl in 2002 at an SOS home in Johannesburg, which was only investigated by police years later because the SOS failed to report it. One investigation into SOS operations in Panama described a pervading “culture of fear and victim blaming” with survivors dismissed as liars – even forced into meetings with their alleged abusers. In one case in Liberia, an SOS staff member who fathered a child with a minor was released from prison after SOS declined to pursue rape charges against him.

Despite hundreds of allegations of abuse, SOS has continued to grow in size and funding

One report commissioned by SOS in 2023 detailed pregnancies and abortions from sexual abuse within multiple SOS villages, and active cover-ups by senior leadership, concealing sexual abuse cases from authorities with a preference to “handle them internally”. It flagged widespread drug use, STIs, and accused SOS leadership of obstructing investigations.

Investigators found that SOS failed to screen donors, some of whom sexually abused children – one victim was even sent to visit an alleged abuser in Austria. The report accused SOS leadership of actively obstructing investigations – downplaying allegations, discrediting whistleblowers, and retaliating against them – citing a systemic failure to act on recommendations from previous investigations. And that was only the first half of the report – the second half was never released to the public.

In Syria, documents show that girls as young as one and a half years old were taken for virginity testing by an SOS staff member in 2016. Investigators also uncovered a pattern of child safeguarding failures, including neglect, survivor silencing and bribery attempts to force recantation, failure to trace and support abuse survivors, and mishandled complaints against senior staff. Senior staff members dismissed for child abuse were later rehired. Others were appointed to high-level positions, despite their records of child abuse at other organisations being well-known.

SOS said they have no records of girls who were subjected to virginity tests upon entering SOS Syria care, and said that “child safeguarding investigations have confirmed that several employees at SOS Syria were involved in serious safeguarding violations,” with allegations of sexual abuse investigated by the International office in 2017, 2018 and in 2021, all of which “found severe weaknesses in human resources practices, particularly in relation to safe recruitment.”

In 2015, media reports emerged that SOS was taking in the children of detainees in Syria, including in a German newspaper in which the National Director himself confirmed the practice. But SOS International said they first became aware in 2017, when five cases were reported to them.

The SOS leadership didn’t launch an internal review or stop forced placements until over a year later, after more complaints from whistleblowers. While SOS delayed, more than 50 children were separated from their parents and placed at SOS, according to the charity’s own records.

Yet the issue of detainees’ children remained buried from the wider public and SOS donors until 2023. A senior International SOS staff member told us that when staff from the Syria office raised the issue of children of detainees with SOS HQ, “senior executives didn’t want to know the details and hid away from concrete action and responsibility.”

Abdulrahman Ghbeis believes he was targeted by the state for his work with the Red Crescent.

From rooftops in besieged Ghouta, with no internet and faint signals, Abdulrahman chased every possible lead to free his imprisoned wife and child – begging various factions for help, sending the names of detainees the regime might want. But the regime’s demands kept growing –from four to 25 names. Abdulrahman couldn’t meet them.

When UN delegations visited, he met them and explained his work with the Red Crescent, his missing wife and child. They listened, nodded, then said we can’t do anything. Desperate, he turned to bribes. The officers named their price: 30m Syrian pounds (£1,718.11). Abdulrahman scraped together 5m for the first instalment. After 20 days, the deal fell apart.

Over the years, several prisoner exchange deals rose and collapsed, one after another. In the meantime, Abdulrahman’s family was shuffled between prisons and orphanages.

One time, after nearly three years in air force intelligence custody, his wife and sister were moved to a different branch and briefly reunited with the children – Mohammed, Layla, and Layan. A prisoner exchange seemed imminent. But three days later, it fell apart. The children were taken from their mothers again, this time ending up together at the Saboura centre – another SOS village outside Damascus.

Over the years, several prisoner exchange deals rose and collapsed, one after another. In the meantime, Abdulrahman’s family was shuffled between prisons and orphanages

“By then, I was broken,” Omama said. “I’d seen my daughters – then lost them again.”

Weeks later, another deal was on the table. It was March 2018 and Ghouta was buried in smoke as Russian and regime forces launched a relentless assault. “We hid in basements and tunnels,” Abdulrahman said. “We thought we’d die there.” Amid the chaos, an evacuation deal to Idlib was arranged for Abdulrahman. He begged for his family’s release, and negotiators assured him that his family would be released: “Their file is ready.”

But on 23 March, the deal collapsed. Instead of returning Abdulrahman’s family to him, the regime sent his wife and sister to Isis-controlled Al-Hajar al-Aswad – to be traded for captured regime soldiers.

The children were not included in the prisoner exchange.

“Where are the children?” Iman and Omama pleaded.

Three days later, a Red Crescent officer was sent to help reunite them with their kids.

But at SOS, staff refused to release them. “We can’t release the children without orders from air force intelligence,” they said.

Finally, after waiting all day, Iman and Omama returned to SOS with the paperwork.

“Layla was overjoyed and hugged me and Iman, but Layan clung to her caregiver, crying,” says Omama, “She didn’t recognise me.”

Mohammed’s SOS “mother” collapsed to the floor, sobbing. “For God’s sake, take care of him,” she begged.

“Of course I will,” Iman told her. “He’s my son.”

When Iman stepped out of the car carrying Mohammed in her arms, he was wearing a red shirt – quiet, unsure. Abdulrahman studied his face: the nose, the expression. Was it really him?

Abdulrahman Ghbeis and his son Mohammed reunite after three years of forced separation.

Over three years, Abdulrahman had only seen his son twice – in photographs. The last came in 2017, when he learned Mohammed was at SOS. The alternative mother at SOS, who cared for Mohammed, sent two photos of him celebrating his second birthday: long hair, dressed neatly, a rose behind him. Abdulrahman clung to them, memorising every detail, tracing his nose and eyes. “He looked like me.”

Now, seeing his son in person for the first time, it was the dimples that broke him. “He was mine.”

Abdulrahman hugged him close, hoping he’d hold on, but three-year-old Mohammed pulled away. He understood: he was a stranger. It took six months for Mohammed to warm to Abdulrahman. “I had to show him, day by day, what it meant to feel safe with his father.”

Iman, meanwhile, withdrew – distant, closed off. She still can’t speak of what happened, says Abdulrahman. “It’s her nightmare more than mine.”

Across Syria, families remain scattered and searching. Many children don’t know whether they are children of detainees, or who their families are, while others who remember their real names are still denied access to their records.

We have found evidence that SOS repeatedly blocked reunions between children and relatives ready to care for them – turning families away, stalling with vague promises, or deferring to air force intelligence. In May, SOS launched a tracing channel. One man searching for his nieces submitted a request. No one replied.

Abdulrahman and Iman never received any support from SOS. Of 21 Syrian children of detainees reunited with their families, only one family got SOS psychological support – and only after the mother explicitly asked for help.

Civil society groups have pushed for justice. In May, the government finally established a Committee to Monitor the Fate of Detainees’ and Disappeared Children, but so far it has failed to establish a system for families to search or any path to accountability. “They promised investigations,” Abdulrahman says. “We’re still waiting.”

A new team at the Ministry of Social Affairs joined three other ministries to take over the orphanage investigation, pledging to uncover the fate of detainees’ children and the forcibly disappeared. Since then they have announced no new findings from their investigation. A spokesperson said it has seven part time members and may need to rely on volunteers as it is “overwhelmed by documents”.

Several employees who were involved in the disappearance of children of detainees continue to work at the ministry. Five orphanage directors were arrested in July, reportedly for their role in the disappearance of children. Three have since been released. At the end of July, like Samar Daaboul, head of the Syria board, Samer Khaddam, the SOS national director, was also removed from his position and is currently detained. Two former ministers from the Ministry of Social Affairs were also detained.

SOS acknowledged regret that many children were never reunited with family and admitted no apology or compensation was given. They pledged to support reunification by hiring independent lawyers for two new investigations and sharing files with Syrian authorities. The first, by main funder SOS-Kinderdörfer weltweit, began last summer. On August 18th they noted former SOS Syria staff's reluctance to cooperate with their investigation and that children were admitted to SOS Syria without meeting their normal admission criteria, for example, meeting with the families and obtaining the child’s official documents. The required family reunification process was also ignored, they added. Investigators have identified five child safeguarding incidents involving detainees’ children.

A UK Charity Commission spokesperson said SOS Children’s Villages UK submitted a serious incident report earlier this year concerning its funded activities in Syria – £353,000 between 2018 and 2024. The commission has since opened an ongoing compliance case. In July, SOS UK ended all remaining sponsorships in Syria.

In May, SOS International said children’s rights, safety, and dignity remained its “moral compass”, vowing to keep supporting and protecting them. Two months later, SOS-Kinderdörfer weltweit announced plans to close its Syria programs within three years, admitting that “the wellbeing of the children can no longer be guaranteed”. Benoit Piot, the interim CEO at SOS International said that despite their biggest funder pulling out, they hope to continue operations in Syria.

In July, SOS Children’s Villages International defended its decision to take in children of political detainees, stating that denying care would go against its core values. “We are unable to provide specific information regarding the number of countries in which we provide care for children of incarcerated parents,” they added.

On the fate of detainees’ children in Syria, it said only: “The facts remain unclear.”

On 1 September 2018, Mohammed slept in his own bed for the first time – in new pyjamas, under a quiet roof, both parents just steps away.

Abdulrahman stood in the doorway, listening to the steady rhythm of his breathing. Trying to reconcile the boy in front of him with the child lost to the years.

He’s never told Mohammed the full story; he agreed with Iman not to discuss it at all. “No one wants to revisit that time.”

Instead, he rewrites the past – soft stories, crafting small joys to tell his son. “We used to play with you when you were little,” he tells him. “Your first tooth came out, and we were so happy.” Maybe if he says it enough, it will feel true.

Still, Mohammed feels the weight. “He tells us some details,” when memories slip through. And when they do, Abdulrahman gently pulls him back.

“I try to make him forget.” Because it still lives inside Abdulrahman. All of it. One day, he’ll tell his son everything. For now, he gives him the only truth a child should carry.

“When you were young, we kept you safe.”

This article is part of the Syria’s Stolen Children investigation coordinated by Lighthouse Reports and in partnership with The Observer, Syrian investigative journalism groups SIRAJ and Women Who Won The War, BBC Eye, Der Spiegel in Germany and Trouw in the Netherlands.

Additional reporting by Bashar Deeb, Mais Katt, Haya Badarneh, Jess Kelly, Mohannad Alnajjar, Monica C Camacho, Ali Al Ibrahim, Ahmed Haj Hamdo, Charlotte Alfred.

Photographs by Lynzy Billing and Women Who Won the War