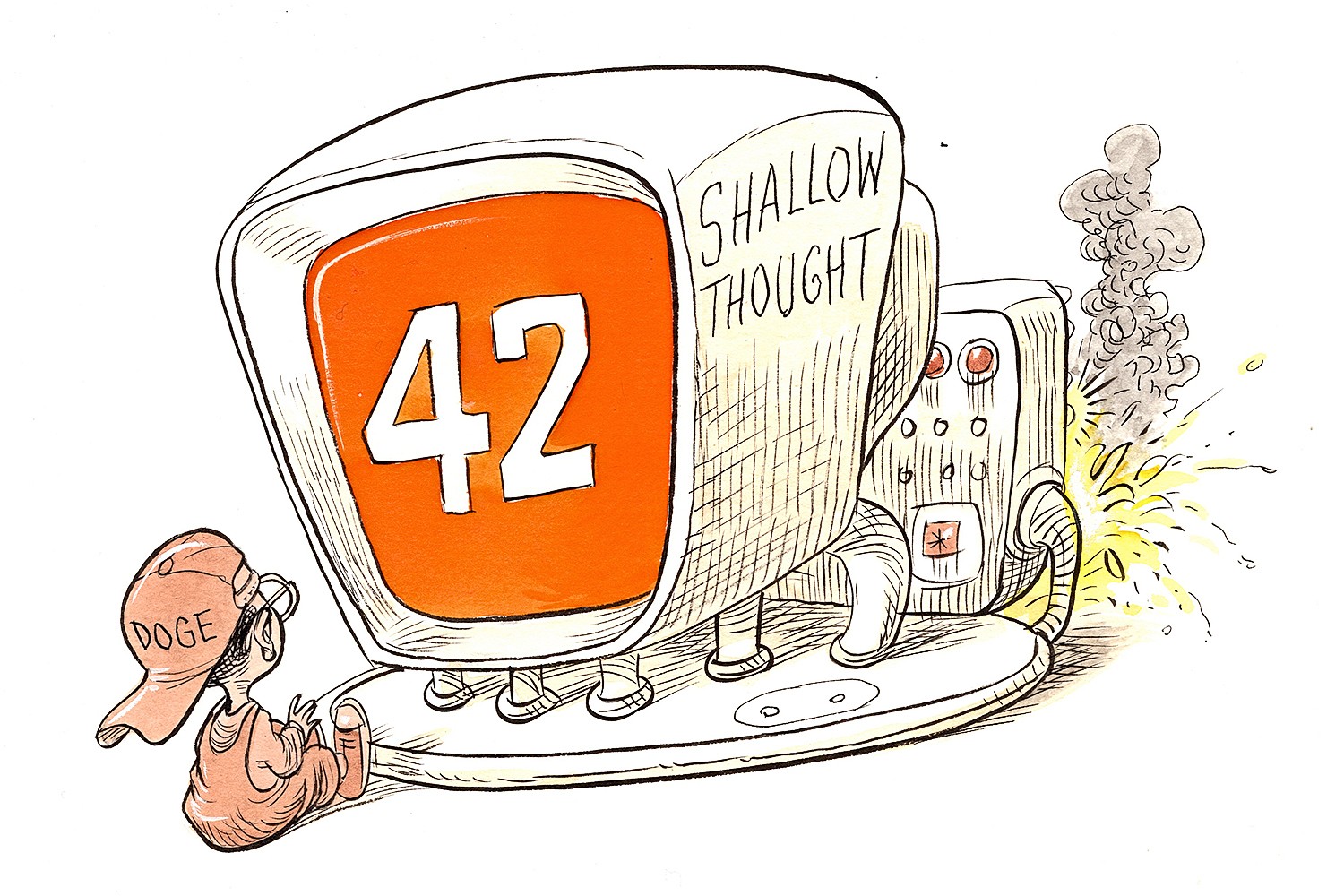

Illustration by Chris Riddell

When I interviewed him back in 2011, Elon Musk ended an enthusiastic conversation about his plans to colonise Mars by cracking a joke (one that he has used several times since). I had asked if he planned to be on the first manned voyage to Mars. He said: “I think it would be great to be born on Earth and die on Mars – just hopefully not at the point of impact.”

In his biography of Musk, Walter Isaacson notes that the billionaire’s humour can veer from the puerile (employing the phrase “open butthole” as a voice command to a Tesla to open its rear charging point) to “a metaphysical science-geek droll cleverness”. Although Musk grew up in South Africa, that humour has been shaped by a quintessentially British strand of comedy. He loves Monty Python. One sketch inspired him to name a small computer at his first company “The Machine That Goes Ping”. He later tried to get a robot to move like John Cleese in the Ministry of Silly Walks sketch.

Most influential of all on Musk, though, has been the great British science-fiction satire The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the “five-book trilogy” written by the late Douglas Adams between 1978 and 1992. Musk first read it during a dark phase of his adolescence. As he later told Isaacson, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide helped me out of my existential depression, and I soon realised it was amazingly funny in all sorts of subtle ways.”

When it comes to their science-fiction influences, Silicon Valley types tend to be either Star Trek or Star Wars. Musk has had his moments with both: he named SpaceX’s Falcon rockets after those in Star Wars, and accidentally re-cremated the ashes of James Doohan, Scotty from Star Trek, when one of his rockets exploded soon after a launch that was to carry them to their final frontier in space.

But he has found most inspiration in The Hitchhiker’s Guide throughout his entrepreneurial career, including his desire to go to Mars and his efforts to humanise artificial intelligence. As he tells Isaacson: “I took from the book that we need to extend the scope of consciousness so that we are better able to ask the questions about the answer, which is the universe.”

Re-reading the books for this article, for the first time since my own adolescence, I was struck by how timely they feel in the moment we are living through. The hi-tech future the books envisage in some ways seems quite close, certainly much more so than when I first read them, back when the most hi-tech thing I owned was a first generation digital watch (the sort that just told the time). But, in contrast to the techno-utopianism emanating from Musk, these are books dominated by improbable happenings, unforeseen consequences, and the almost constant ability of tech innovations to disappoint, unsettle and threaten at least as much as they improve the quality of life (on Earth and elsewhere). Not for nothing does the eponymous guide – “the most remarkable... book ever to come out of the great publishing corporations of Ursa Minor” – which is stuffed full of a wild mix of real and fake news about goings-on across the universe, have printed in large letters on its cover the words DON’T PANIC. (In 2018, to cheer himself up, Musk launched a Tesla Roadster into orbit, with a copy of The Hitchhiker’s Guide in the glove compartment and the words DON’T PANIC on a sign on the dashboard; it is reportedly currently not far from Mercury, on its fifth orbit of the Sun.)

Many of Adams’s unintended disappointments come from efforts to humanise inanimate objects, ranging from annoyingly cheerful lifts to the severely depressed robot Marvin, the paranoid android (a character who inspired the title of a song by Radiohead). But the biggest disappointment of all is the seven-and-a-half-million-year calculation by the computer Deep Thought of the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything (which turns out to be 42). As Deep Thought observes: “I think the problem, to be quite honest with you, is that you’ve never actually known what the question is.”

Related articles:

Beeblebrox is a possible crook, manic self-publicist and said to be out to lunch– ideal presidential fodder

Beeblebrox is a possible crook, manic self-publicist and said to be out to lunch– ideal presidential fodder

Telling Isaacson how they came to nickname their daughter Y, or Why?, Musk’s sometime girlfriend Grimes credits explicitly this lesson from the Guide: “Elon always says we need to figure out what the question is before we can know the answers to the universe.”

Incidentally, the Hitchhiker books contain plenty of characters whose names would fit in nicely with those Musk and his various baby-mamas have given to his fast-growing army of offspring, including one incorporating an equation (Zipo Bibrok 5 X 108) and a girl called Random. The universe as described by Adams tends, like our current popular culture, to reduce everything to mere entertainment (including its own final moments, which can be witnessed over a gourmet meal in The Restaurant at the End of the Universe).

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

It is also an extremely unequal place. To quote the original BBC radio play where The Hitchhiker’s Guide debuted: “Many men of course became extremely rich, but this was perfectly natural because no one was really poor, at least no one worth speaking of.”

Earth itself turns out to have been manufactured by a company that builds designer planets for the super-rich. We encounter a sex worker with an economics degree who offers a “very special service to rich people”, including cooing comfortingly: “It’s OK, honey, it’s really OK, you got to learn to feel good about it. Look at the way the whole economy is structured.”

Anyone who has listened to billionaire Silicon Valley tech bros talking up their latest sporting enthusiasms on the Joe Rogan podcast will find something familiar in the scene where two of the main characters, Ford Prefect and Zaphod Beeblebrox, rave about the latest rich-boy-toy spacecraft for riding flares from the sun – “one of the most exotic and exhilarating sports in existence and those who can dare and afford it are amongst the most lionised men in the galaxy. It is of course stupefyingly dangerous – those who don’t die riding invariably die of sexual exhaustion at one of the Daedalus Club’s Apres-Flare parties”.

Ford Prefect is a roving reporter for the Guide, while the two-headed Beeblebrox is president of the Imperial Galactic Government. Observers of today’s earthly politics may not be surprised to learn that Beeblebrox is “ideal presidential fodder”, being an “adventurer, ex-hippy, good-timer, (crook? quite possibly), manic self-publicist, terribly bad at personal relationships, often thought to be completely out to lunch”. Conspiracy theorists may latch on to Adams’s comment that he wielded exactly no power (the secret job of president being “not to wield power but to attract attention away from it”).

As much as anything, The Hitchhiker’s Guide is a satire on government. It opens with two acts of bureaucratic cruelty. First, Arthur Dent, the main human hero, discovers from the presence of bulldozers that his home is about to be demolished by the local council to make way for a bypass. That coincides exactly with the destruction of the Earth by aliens from the planet Vogon (“one of the most unpleasant races in the Galaxy – not actually evil but bad-tempered, bureaucratic, officious and callous”) to make way for a hyperspatial express route.

“There’s no point in acting all surprised,” the Vogon commander tells the protesting earthlings. “All the planning charts and demolition orders have been on display in your local planning department in Alpha Centauri for 50 of your Earth years, so you have had plenty of time to lodge any formal complaint.”

It is easy to see how this would resonate with Musk, who as Isaacson recounts, has suffered an abundance of bad experiences with inflexible government bureaucracy. Since taking on the leadership of Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency, however, has adopted a brutally Vogon approach to getting things done, slashing US aid, demanding extra reporting from all government employees and arbitrarily firing them in droves. His days in government may soon be reduced so he can spend more time running his companies. But he may come to wish he had taken to heart perhaps the most explicit, least funny message in The Hitchhiker’s Guide books: “It is a well known... fact that those people who most want to rule people are, ipso facto, those least suited to it.”