Less than three weeks ago, Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump were planning a summit in Budapest to end the war in Ukraine. Now they are threatening each other with a return to the kind of full-blown nuclear testing effectively banished by treaty 30 years ago.

What went wrong? Nothing too serious – yet. The US military is not at Defcon 1. But for the first time since Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Trump has responded to Russia’s nuclear sabre-rattling with a little of his own. It could backfire.

In a 60 Minutes interview with CBS on 31 October, Trump claimed Russia and China were conducting underground nuclear tests and that the US was therefore “going to test nuclear weapons like other countries do”. There is no evidence for his claim, although Putin has recently boasted about new Russian nuclear-powered missiles and torpedoes.

Then, two days later, the US energy secretary, who is responsible for developing and producing the country’s nuclear weapons, said any tests would only involve “non-critical” explosions.

It is possible that Trump misunderstood the briefing he got from Department of Energy officials, or it could be that he has decided to push them to go further than their original plans. Either way, mixed signals aren’t good for stable deterrence, and last Wednesday evening, in a highly theatrical Kremlin meeting of Putin’s security council, his defence minister recommended immediate preparations “for full-scale nuclear tests”.

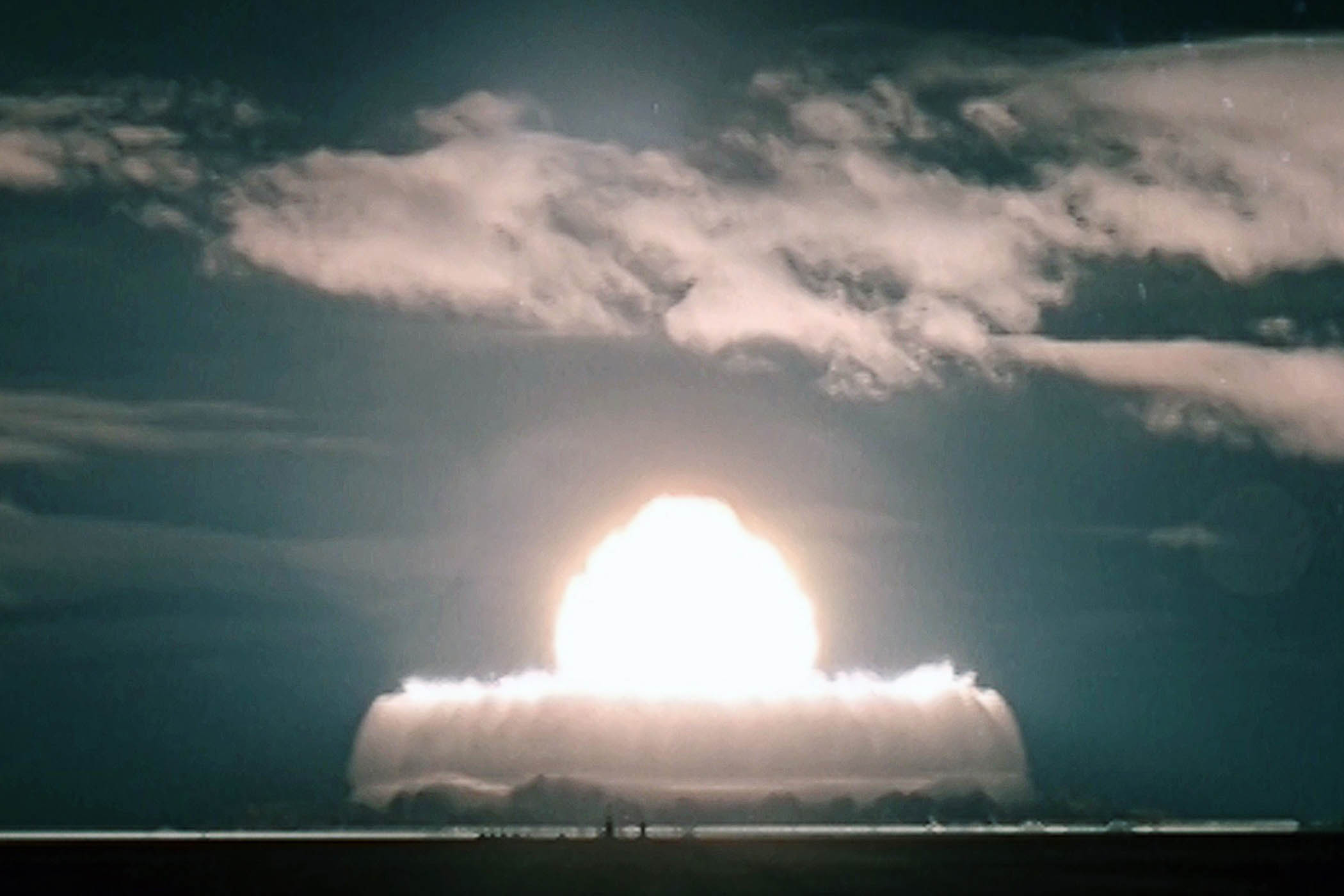

He advised using Russia’s Arctic test site on the island of Novaya Zemlya, where the biggest nuclear blast in history irradiated much of the far north in 1961.

So what did US energy secretary Chris Wright mean by “non-critical” explosions? There are various ways of scaling back a nuclear weapons test. One is to remove the nuclear core from the weapon and substitute other heavy metals for the plutonium and uranium used in the real weapon. This can demonstrate whether various components like conventional explosives, fuses, and arming mechanisms are working properly.

Another is to use a quarter or half scale nuclear weapon. This will produce a nuclear reaction, but not sufficient to produce a full nuclear blast. A third is to simulate nuclear conditions using other tools, such as the US National Ignition Facility at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in California, which produces nuclear fusion in conditions similar to those in a thermonuclear bomb.

Related articles:

Some experiments of this type have happened around the world since the main nuclear powers stopped testing in the 1990s. But full-on underground nuclear tests have not been conducted for a generation. The Soviet Union’s last test was in 1990, the US in 1992, France and China last tested in 1996. While the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) has never formally come into force, it has been broadly observed since that time, with 178 countries ratifying the treaty.

The main aim of CTBT has been to stop the development of new nuclear weapons, and to prevent upgrades of existing warheads. This is the real reason that people are worried by Trump’s apparent and repeated escalation. Simple nuclear weapons such as those used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki are relatively easy to make, and their physics is well known. Many countries could make one, if they tried. The problem is that they are extremely heavy, meaning they could not be carried by a missile, but would have to be flown by a heavy bomber, or transported by road or sea.

To reduce the weight of the bomb from the five tonnes of the first bombs, to the 100kg-200kg required to be fitted on to a modern missile, and at the same time increase the explosive power by a factor of 10, from 15,000 tonnes of TNT in the second world war bombs to 150kT today, is extremely difficult.

Those with the most to gain would be those countries with the most primitive designs – particularly North Korea

Those with the most to gain would be those countries with the most primitive designs – particularly North Korea

The designs of these modern weapons are incredibly complex and require large amounts of expertise and understanding. They are also very sensitive to just how they are put together – get something just a little wrong and the weapon will not fire.

To learn how to make such miniaturised weapons, the early nuclear powers carried out huge amounts of testing throughout the second half of the last century. America conducted 1,030 such tests, Russia 715, France 210, and Britain and China 45 each. By contrast, the emerging nuclear powers have done much less testing, India conducted three tests, Pakistan two and North Korea six.

If the moratorium on full-scale nuclear testing were breached, the US would have the least to gain. It could confirm that new designs, created to replace weapons developed in the 1980s work properly. Old designs are theoretically still solid, but their components have been irradiated for decades, and replacement parts are often no longer available. There is some advantage in checking that updated weapons still work, or even that old designs are still reliable. But the main nuclear powers know almost all that is to be known about the physics of these warheads.

Those with the most to gain would be those countries with the most primitive designs – India, Pakistan and particularly North Korea. China could also move into the front rank of nuclear weapons states with more sophisticated warheads. Breaching the effective test ban might also encourage other states to test weapons, with Iran being a possible example.

Effectively outlawing nuclear weapons testing has had the effect of freezing the advantage of the main nuclear powers over would-be weapons states. If Trump means what he says, more countries with more powerful and more easily delivered nuclear weapons would be the likely outcome.

This would only be the latest chapter in the decline in nuclear weapons limitations treaties. The US withdrew from the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019, because it believed that Russia was cheating and creating a medium-range nuclear missile in secret. America also withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, because it wanted to develop a missile shield for North America. Now the CTBT could be next, and there is no sign of negotiations on a New Start 2 treaty, to replace the strategic weapons reduction treaty due to expire next year.

Uneasy times in nuclear weapons control, and the law of unintended consequences continues to apply.

Bernard Gray was chief of defence materiel and UK national armaments director from 2011-2015

Photograph courtesy www.atomicarchive.com