One of the most famous – and significant – artworks in the United States is an engraving made in 1770 by the silversmith Paul Revere. It is called The Boston Massacre, or The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston on 5 March 1770 by a party of the 29th Regiment. Think of it as an 18th-century meme in its bold depiction of British soldiers firing into a crowd after locals had thrown stones and ice balls at a lone guard outside the custom house. Five people were killed by the redcoats, including Crispus Attucks, a sailor and dockworker of Native (Wampanoag) and African American ancestry; he lies bleeding in the image’s dramatic foreground.

When the film-maker Ken Burns and I meet for our New York walk, Revere’s print springs into our conversation, as relevant as it was two and a half centuries ago. Just five days before our encounter, 37-year-old Alex Pretti, an ICU nurse, was murdered on the streets of Minneapolis, shot and killed by two customs and border protection officers during a violent confrontation at a protest in the city. Burns does not mince his words.

“I think we should call it the Minneapolis massacre, and Paul Revere should come back from the dead and do an engraving showing our guy being shot. Pretti is no different than Crispus Attucks, or the other people who were killed – five people eventually, the fifth died of his wounds.”

The Bloody Massacre, engraved by Paul Revere, depicts the 1770 killing of Boston protesters by British troops

That careful delineation of who died when and of what is very Ken Burns. Later that evening I’ll hear him remind a rapt audience at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that Revere did not say “The British are coming!” but rather “The regulars are coming out!” He makes the point emphatically, twice, and it reveals a profound truth about Burns. Storytelling, powerful narrative, is paramount for him, but only if it is backed by facts painstakingly unearthed.

It’s this that makes his work feel so fresh. We know who won the American Revolution, or the American civil war, yet Burns makes us hold our breath. “Good history is making you think that it might not turn out the way it did, and that is the key to storytelling,” he says.

We meet for our walk at the SoHo Grand, in downtown Manhattan on West Broadway. A note about the length and scope of our stroll: New York City is locked in the grip of a historic cold snap when we meet – we were meant to walk over the Brooklyn Bridge, but with the temperature hovering about -12c, never mind the wind, we’ve decided that would have been unbearable. But the neighbourhood in which we instead find ourselves has a particular resonance to his latest project, an epic documentary about the American Revolution that has been a decade in the making.

We head north and east, towards streets whose names I’ve always known, as a New Yorker: Greene Street, Thompson Street, MacDougal Street, Sullivan Street. These days they are the epicentre of downtown cool; but let’s head back 250 years or so and consider Manhattan back then. When you’re walking with Ken Burns, you can’t help but feel that history is all around you.

“This was farmland,” Burns says, gesturing at the traffic and the fancy boutiques. “And once there were streets” – as Manhattan crawled upwards from its southernmost tip – “they had different names: Greene Street was Elm Street, Sullivan was Locust Street. But they were renamed for Revolutionary war generals: we’re walking in a memorial to the Revolutionary war.”

Related articles:

Winter weather obscures the Brooklyn Bridge on 25 January

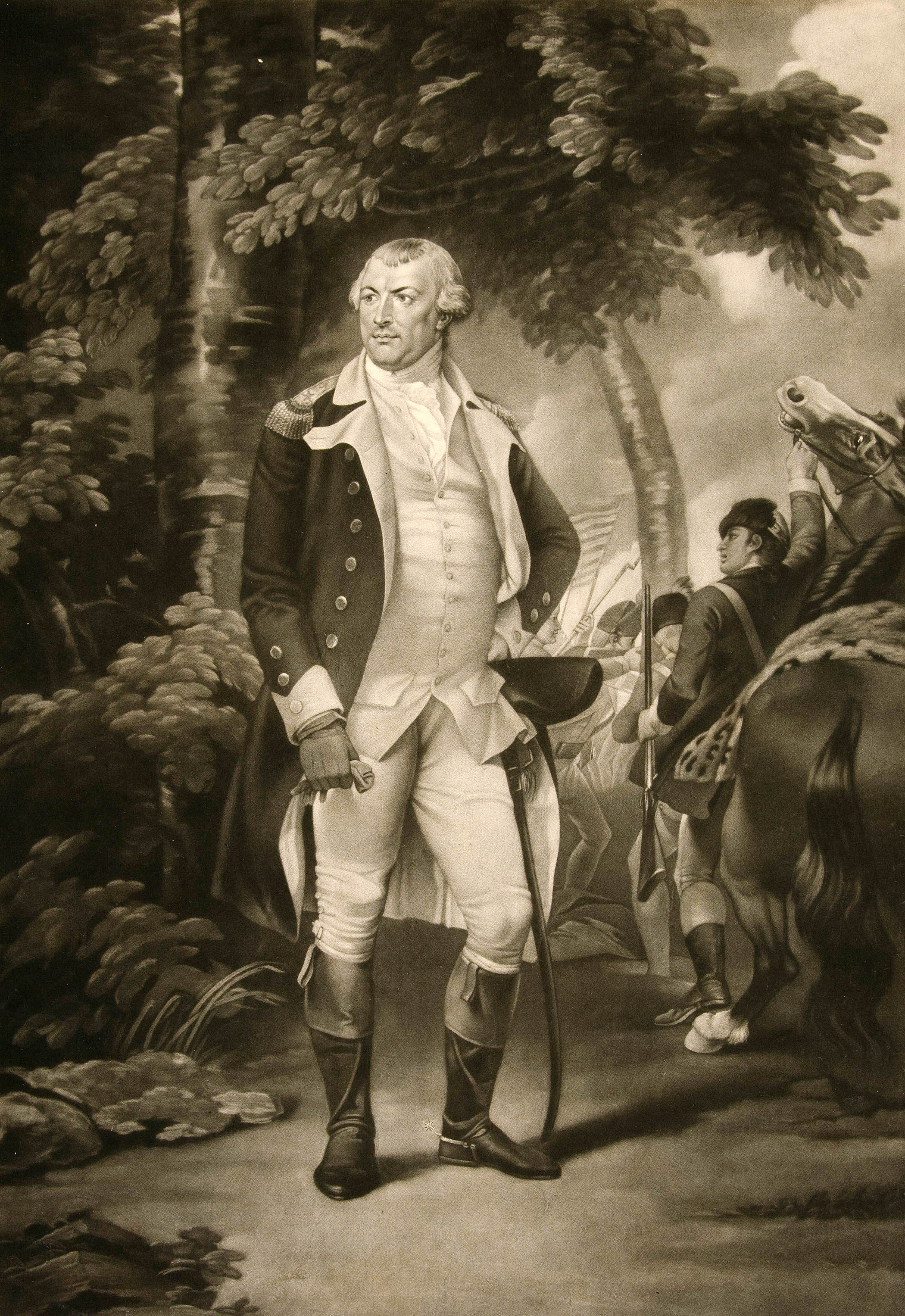

Nathanael Greene was George Washington’s “great second in command”, Burns says; John Sullivan crossed the Delaware River with Washington; Lafayette, after the great French marquis who became a commander in the Continental Army, is not far away; West Broadway itself, he tells me, was once called Laurens Street – after General John Laurens, a trusted aide-de-camp of Washington’s who was raised in a slaveholding family and came to be a prominent abolitionist.

Burns is the man who tells America’s story to itself. On the day we meet, his very first film, The Brooklyn Bridge (1981), was added to the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry; but it was his epoch-making 1990 documentary series The Civil War that truly put him on the map. Without any re-enactments, using only the still photographs of the era, the nine-part film makes the viewer feel eerily present at the conflict, thanks to what is now officially called “the Ken Burns effect”: panning across still photographs to pick up details and bring a remarkable sense of movement. Baseball, jazz, Prohibition, the Vietnam war, the Roosevelts, the country’s national parks: all have been illuminated by Burns’s discerning lens. And there are of course his collaborators: The American Revolution is written by the historian Geoffrey C Ward, and his co-directors are Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt. Not forgetting the voices who bring historical figures throughout the ages to life: Morgan Freeman, Tom Hanks, Meryl Streep, Paul Giamatti… When Ken Burns calls, it’s pretty clear everyone picks up the phone.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

I grew up in New York, but when I learned about the Revolutionary war at school, the focus was never on my native city. There was the aforementioned Boston Massacre and Revere’s famous ride to Lexington, Massachusetts, to warn of the approach of British troops (remember: “The regulars are coming out!”); there was the vision of General George Washington and his troops encamped in the freezing winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania – a snapshot from the past that seems especially pertinent on this bitter day.

We stand on the corner of Greene Street for as long as is feasible (our photographer Maria’s hands are ungloved). While Burns is a fount of knowledge – the generals’ names and their roles trip off his tongue – he lets the listener know that history is a journey of discovery for him too. “I had no idea that the Battle of Long Island was the largest battle of the war,” he says. The first major engagement after the signing of the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776, it was a British victory. Washington’s troops escaped, near miraculously, across the East River from Brooklyn to Manhattan – precisely where the Brooklyn Bridge stands now – one rainy August night and so lived to fight another day. “It’s why the final shots of our film are fireworks going over the Brooklyn Bridge, without any other comment. This was exactly where the retreat happened that saved the whole republic.”

Ah, saving the republic. In 1787, at the Constitutional Convention, where the second founding document of the United States came into being, Benjamin Franklin was asked, “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a monarchy or a republic?” Franklin famously replied: “A republic – if you can keep it.”

So here we are in 2026: when citizens are being executed in broad daylight and people abducted from their cars, homes and workplaces. The institutions of the United States are under sustained assault, the government dismantled, the Smithsonian Institution pressured to show President Trump its plans for exhibits on America’s 250th birthday. The aim is to restore, as the White House has it, “truth and sanity” to how American history is told – meaning, for instance, removing exhibits related to enslavement at Philadelphia’s Independence National Historical Park. (The city of Philadelphia is taking legal action against the removal.) Ken, Ken, what do we do?

Nathanael Greene was George Washington second in command during the American War of Independence

“It’s obviously terrible,” Burns says. “But Black people aren’t going to disappear. Women are not going to disappear. Native people aren’t going to disappear. They’re here. But the fact is that while it is in the authoritarian’s interest to make a simplistic theory – the master race, say – it never works out. And for those who despair: well, I would remind them that things were much more divided during our revolution and during our civil war, obviously, where we murdered 750,000 of our own people. During the Vietnam period – hundreds of bombings across the country. So there’s a kind of narcissistic self-involvement with ourselves in this moment, saying ‘the sky is falling’. Historical perspective gives you, if not optimism, but just some measure to say, well, this is unprecedented, but there have been hard times before.”

By now we’ve got ourselves out of the cold and have retreated to the bar at the SoHo Grand; coffee warms me up, while Burns opts for green tea. He speaks fluently, passionately, in eloquent paragraphs. The 12 hours of his film allow the viewer to understand what a long and terrible war the revolution was. That to side with the “patriots” was not obvious, to say the least.

“My job is to make films about our history,” Burns says, “but in the course of it, I’m invited into a discussion of what it really means. There is something very special about the fact that before July 4, 1776, everybody – more or less – was a subject under authoritarian rule. But then, in what was just then called the United States, officially those people became citizens that day.”

He moves seamlessly from the past to the present: “The responsibilities of citizenship are so deep, and so demanding. This is what is meant by ‘the pursuit of happiness’ – not objects in a marketplace of things, but lifelong learning in the marketplace of ideas. Abraham Lincoln, in his address to Congress in 1862 [the middle of the civil war] said: ‘The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.’ We must act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we can save our country. It is asking both an individual and a collective consciousness to be made manifest.

“You know,” he says, smiling, “if you look at what happens, in the end, to tyrants – things don’t work out for them.”

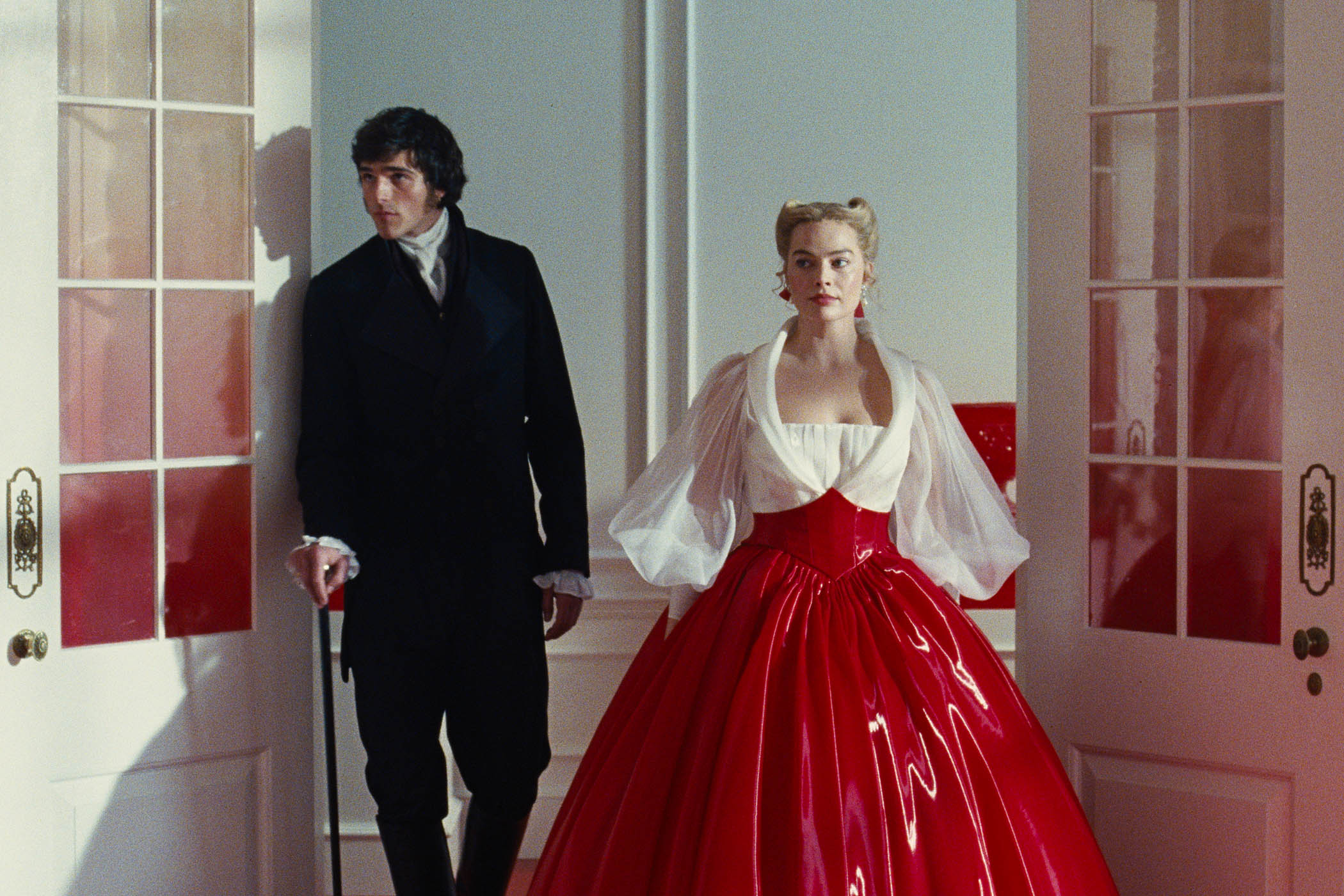

Burns is not blind to the flaws of the founders. “All men are created equal,” wrote Thomas Jefferson – famously a man who thought he could own his fellow human beings, just as Washington did, as did so many of the men who made the United States. Burns’s film gives us not only their stories as the eight years of the war unfold but, crucially, the stories of Black Americans, women, Indigenous Americans. It is an engrossing, encompassing portrait, and all the more remarkable because, hey! – this was the 18th century and photography had not been invented yet. The film’s blend of talking heads, arresting voices, contemporary art and re-enactment done with the lightest of touches is truly compelling. Audiences have been responding: it’s the first show made for public television (itself under threat from the current administration) to enter Nielsen’s streaming top 10: it began to air in November and by mid-December had logged 565m minutes of viewing time.

When you meet Ken Burns, you are struck by how driven he is, how absorbed he is by his work. He has four daughters, and tells me that the only things he feels he’s good at are making films and being a parent. But the latter he’s very much had to figure out for himself: his mother was diagnosed with cancer when he was six and died just before his 12th birthday. She was, essentially, dying his whole childhood. His father suffered from mental illness. Burns speaks of these events with remarkable openness on Anderson Cooper’s (wonderful) podcast about grief, All There Is. I tell Burns how moved I was by his conversation with Cooper. “I was asked in an interview like this, 34 years ago” – again, the precision of this timing – “what my mother’s greatest gift was. I instantly said: ‘Dying.’ And then I started to cry. Of course, I didn’t want her to die. But who am I without this?” He pauses, takes a sip of his tea. “My late father-in-law was a psychologist, a pretty eminent one. He said to me: ‘What do you do for a living? You wake the dead.’ And it is true. I wake the dead.”

It is true. Ken Burns wakes the dead, and in doing so reminds us what we, the living, might be capable of if we choose to listen to the better angels of our nature.

We part; I wrap up warm against the cold and see the streets of my hometown – Greene, Thompson, MacDougal, Sullivan – as memorials to the past, and reminders of what is possible.

Ken Burns and his co-director Sarah Botstein will be speaking at the British Library on 24 February. The American Revolution will air on the BBC in June

Portrait Maria Spann for The Observer

Additional photographs D Guest Smith/Alamy, Angela Weiss/ AFP via Getty Images, Universal Images Group via Getty Images