A week of rising tension between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates boiled over in Yemen on Friday, descending into a full-scale military confrontation between their competing allies in the country.

The seeds were sown in early December when forces from the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a UAE-backed separatist group, pushed east from their stronghold of Aden to seize swathes of territory along Saudi Arabia’s southern border. This landgrab, the most significant since the Yemeni civil war reached a stalemate in 2022, threatened to remake the country and sparked fears of a proxy conflict between the Gulf’s heavyweight powers.

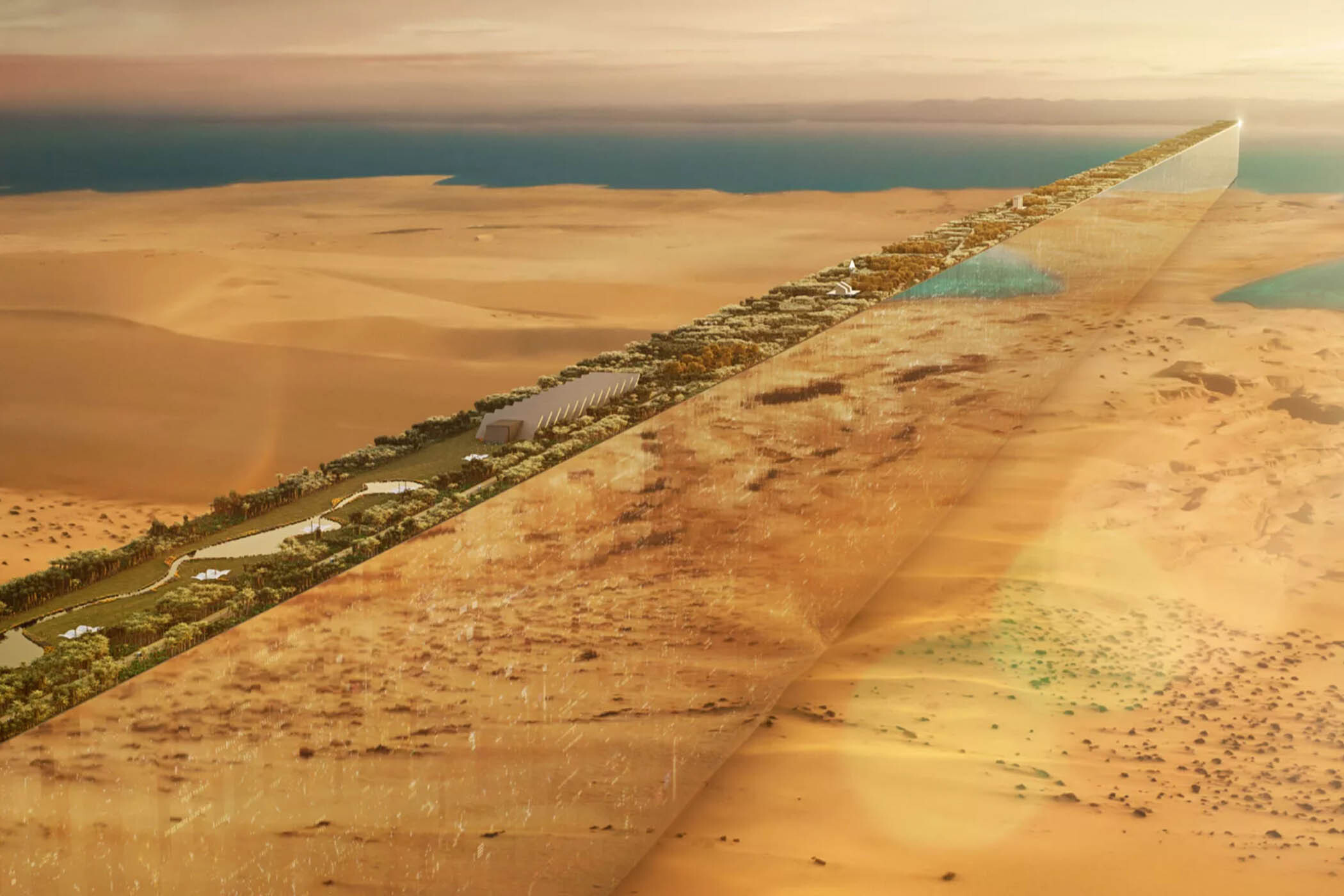

As Saudi-backed government forces melted away, the UAE began to ship in military hardware for new STC positions in the vast governorate of Hadhramaut. By Monday, the STC’s long-stated goal of southern independence, which would end the existence of the 35-year-old Republic of Yemen, appeared to be imminent.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE were once united in efforts to remove the Houthis – but their interests diverged

Saudi Arabia and the UAE were once united in efforts to remove the Houthis – but their interests diverged

This independence bid appears to have been thwarted. Saudi Arabia, which had started striking STC troop positions on Boxing Day, issued an ultimatum to the group on Tuesday, describing the STC’s actions along the kingdom’s southern border as a security threat and demanding the withdrawal of Emirati troops. This threat was coupled with more strikes.

The few still in Yemen scrambled to leave. Heavy fighting for control of military bases between Saudi-backed forces and the STC erupted on Friday, even as STC leader Aidarous al-Zubaidi laid out a “constitution” for the creation of “the State of South Arabia” and pledged to hold an independence referendum within two years.

By Saturday this dream was over. The internationally recognised Saudi-backed government claims to be back is back in control of the province’s capital. Footage posted on social media showed heavy fighting in the desert and the flag of south Yemen being hauled down.

A photograph reportedly shows UAE shipments of vehicles and weapons to STC forces

Farea Al-Muslimi, a research fellow at Chatham House’s Middle East and North Africa programme, said the UAE made a “huge miscalculation”, although he is sceptical it will detach itself from Yemen in the long term. He added that it is likely to conduct “more of a proxy war” via the country’s well-established smuggling routes.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE were once on the same side in Yemen, united in efforts to remove the Iranian-backed Houthis, which control the northern part of the country. But their interests diverged, bringing the countries into competition, and the UAE was keen to gain a strategic footprint on Yemen’s Red Sea coast.

Emirati forces, training and weaponry were instrumental in breaking the Houthi siege of Aden in the early months of the war. Many local fighters in that battle had fought in Yemen’s previous civil war in 1994 between north and south. The 2015 siege and liberation reinforced longstanding aspirations for the revival of a separate southern state that existed in the years between Britain’s departure from Aden in 1967 and unification with the north in 1990.

Most Emirati forces withdrew from Yemen in 2019 along with hundreds of Sudanese rapid support forces, deployed on the country’s western coast under Emirati command. But despite the significant drawdown, their footprint and influence remained. UAE airbases later sprung up on Yemen’s small islands and their military presence was sustained through their sponsored forces.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Yet it was events beyond the country’s borders that contributed to this week’s high-risk standoff between Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) and his former mentor, the ruler of the UAE, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (MBZ).

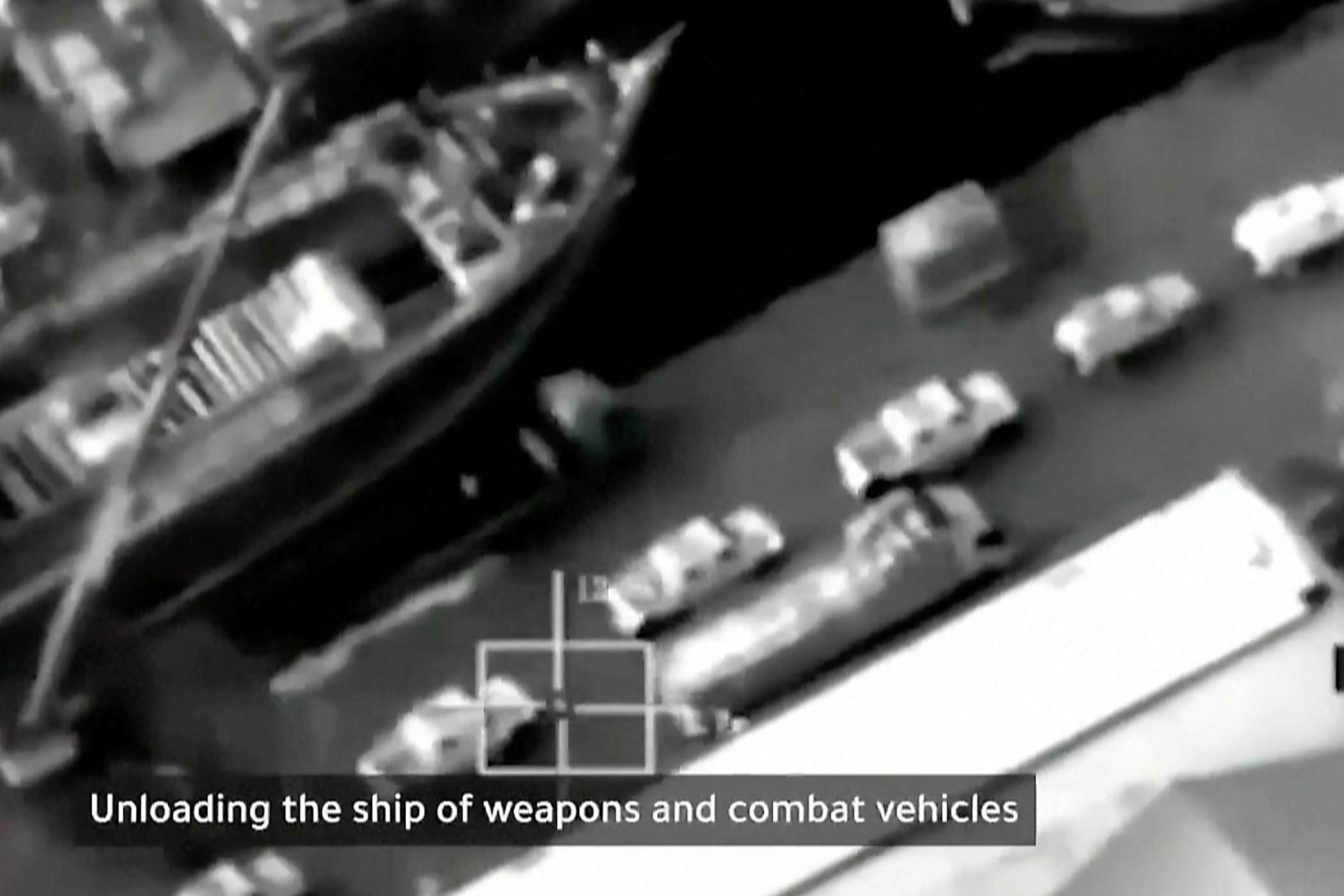

The UAE’s military support of dissident groups extends to Libya and Sudan, using these allies to increase its geopolitical reach. It is accused of running a weapons supply chain to the RSF, which in Sudan is fighting a war against the government forces with which Riyadh sides. The UAE strongly denies arming the RSF.

MBS raised the Sudanese civil war during his visit to Washington in November, an intervention that appears to have antagonised MBZ. Two weeks later, STC forces began their march east into Hadhramaut and Al-Mahra.

Still from a Saudi video that the kingdom describes as a shipment of weapons and armoured vehicles coming from the UAE

The UAE has spent much of the past decade building and funding a network of militias across Yemen. The project began in parallel to its role as a partner in Saudi Arabia’s rapidly created military coalition that intervened in Yemen in 2015 to counter the advances of the Iran-backed Houthis, who hail from Yemen’s north.

The UAE capitalised on secessionist sentiment, underwriting the establishment of the STC in 2017. A divergence of interests and priorities emerged between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, one that often involved military confrontation between competing armed groups backed by the two nations. But what Yemen witnessed in the past few days was of a different magnitude.

Unlike the Houthis, who have an arsenal of ballistic missiles, an Iranian-assisted drone-manufacturing programme and Yemen’s rugged northern mountains for protection from years of Saudi airstrikes, the STC has faced the same firepower in a flat desert landscape with no air cover and none of the same retaliatory methods at their disposal. In a defiant speech on Friday, the STC’s military spokesman described the day’s events as the start of a “decisive and existential” war. But this is a war that the STC, without direct UAE military support, looks as if it will lose in the coming days – if not hours.

The proxy war that loomed last week appears to have been averted, for now, by Saudi strength and the UAE’s volte-face. What remains is an even more fractured country in dire need of a resolution.

Photograph by Aden Independent Channel/AFP via Getty Images, Saudi state television via AP