The colossal cube-shaped skyscraper was designed to tower over the capital of Saudi Arabia, containing an entire district in what would be the world’s biggest building by area. Costing about $50bn, the Mukaab was supposed to create more than 100,000 homes and feature the world’s largest AI-powered display projected on an interior dome. By the end of 2024, excavation at the site in downtown Riyadh was nearly complete. But last week it emerged that construction on the project had been suspended.

Days earlier, the Saudi government announced it would postpone the 2029 Asian Winter Games, as doubts grew that a ski resort set to be built in the desert would be ready in time.

The ski resort at Trojena is just one part of Neom, the huge project that is a centrepiece of Mohammed bin Salman’s effort to transform the kingdom. Other parts of Neom are also being scaled back while the country’s $1tn sovereign wealth fund conducts a review.

The cutbacks are the product of a collision between the crown prince’s ambitions and the constraints of finance – and physics. Nine years after becoming de facto ruler of the kingdom, MBS’s instincts have been tempered at home and abroad. It comes at a time of growing rivalry between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which are competing for influence across the region.

After years of unlimited spending by Saudi Arabia, oil prices have fallen well below what it needs to balance its budget. Meanwhile, the cost of Neom has ballooned from estimates of about $500bn to as much as $8.8tn.

“Some of these engineering challenges have never been done before,” said Azad Zangana, head of Gulf macroeconomic analysis at Oxford Economics. “Ultimately, it might be that they're unachievable, even with unlimited money, or still achievable but with a lot more money.”

After villagers were evicted at gunpoint from a remote region the size of Albania to make way for Neom, in 2020 thousands of workers moved in to begin work on a project that MBS said would provide “living conditions that will drive the future of human civilisation”.

Related articles:

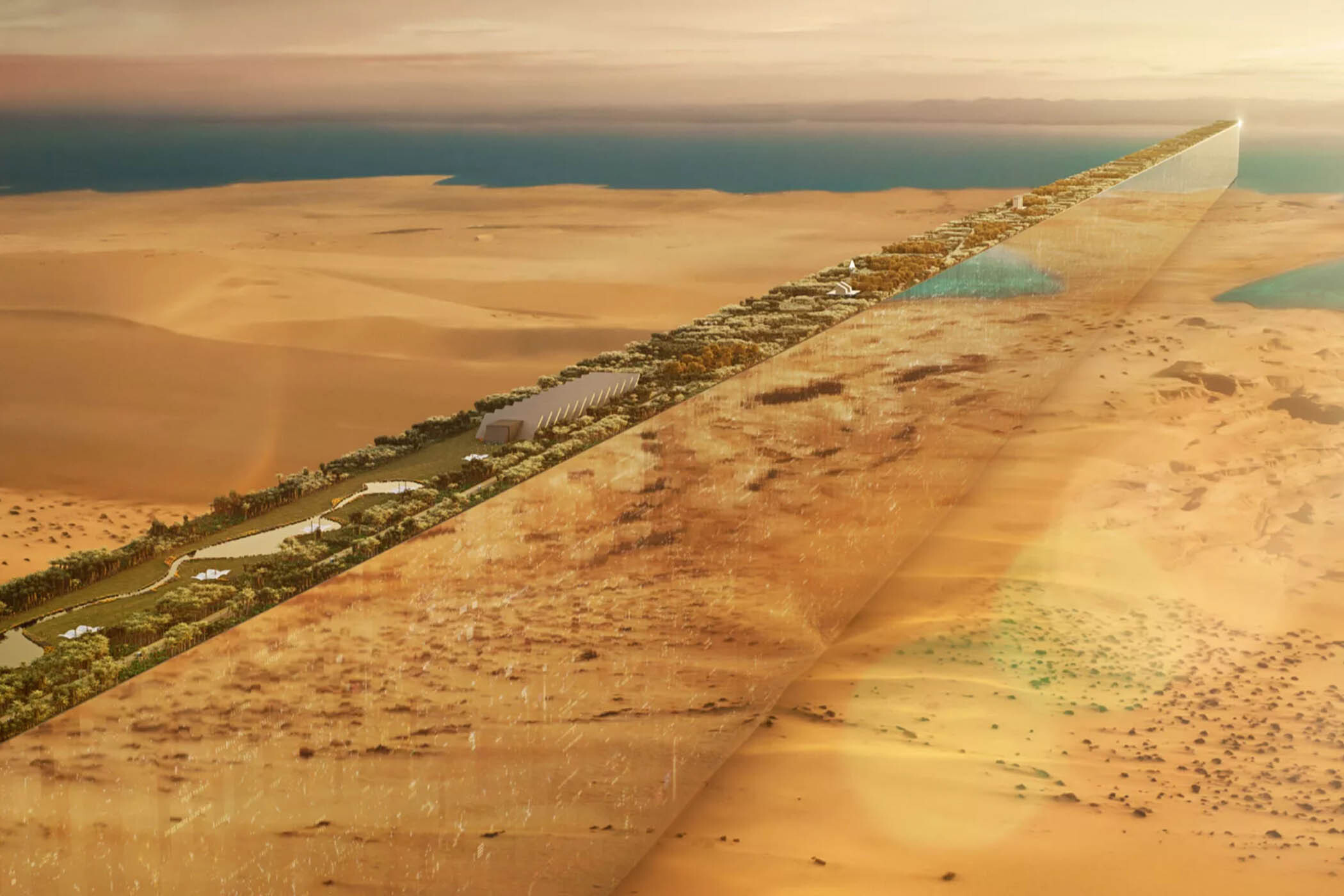

There would be flying cars, giant robotic dinosaurs and a huge artificial moon. Its centrepiece, the Line, was to consist of parallel lines of conjoined mirrored skyscrapers stretching 105 miles (170 km) inland from the Red Sea coast.

Six years on, the goal is more modest: the initial phase of the Line is expected to be 1.5 miles (2.4km) long with 300,000 residents by 2030, instead of the planned 1.5m.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The cutbacks to Neom follow a major spending review of the project launched last year by its new director, Aiman al-Mudaifer. His predecessor was fired in October 2024 after a glitzy launch party for the $4bn Red Sea island Sindalah, which was intended to showcase Neom’s potential and prove to sceptics that the project was moving ahead. It is currently closed.

“Once the former CEO was fired and the new guy came in about a year ago, there’s been a massive contraction of expenditure and of the project itself,” said one frequent visitor to the kingdom.

During a recent trip to Riyadh, he heard that consultants on Neom, including lawyers, engineers and project managers, had been cut back by as much as 90%. It didn’t surprise him. “The Red Sea resorts and developing very high-end luxury tourism for Saudi make sense because that area is completely pristine and has wonderful coral reefs, but who is going to go and live in Neom?”

The giga-projects were conceived in 2017, the year MBS became crown prince. As de facto ruler, he pushed to implement his Vision 2030 initiative, seeking to wean the oil-rich kingdom off its dependence on crude. It was the beginning of a turbulent chapter for Saudi Arabia. Within months, MBS, who had been behind the Saudis’ decision to go to war in neighbouring Yemen, imposed a blockade on Qatar and held captive the Lebanese prime minister, Saad Hariri. The next year, the dismembered remains of a Saudi dissident journalist were found in the consul general’s residence in Istanbul. The CIA assessed that Mohammed bin Salman had personally approved the plan to “capture or kill” Jamal Khashoggi, which the crown prince denied.

The failed interventions revealed the limits of Saudi Arabia’s power and coincided with a changing economic outlook. After surging to $100 per barrel in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, oil prices came down. Projects began to come in above cost and behind schedule as oil revenues fell, widening a budget deficit. In 2023, the government signalled delays to some projects.

“As the crown prince’s tenure went on, he became less interested in foreign exercises and more interested in developing his own country,” said Michael Ratney, who was US ambassador to the kingdom until last year and is now at the Middle East Institute. “He seems to have matured as a leader and became much more clear-eyed about where Saudi strengths lie and how he could help achieve his goal of turning Saudi into a normal society.”

‘Some of these engineering challenges have never been done before. It might be that they're unachievable, even with unlimited money, or still achievable but with a lot more money’

‘Some of these engineering challenges have never been done before. It might be that they're unachievable, even with unlimited money, or still achievable but with a lot more money’

Azad Zangana, head of Gulf macroeconomic analysis, Oxford Economics

Official budgets show the Saudi government began making deep spending cuts in recent years, while leaning on its sovereign wealth fund to finance outsize projects such as Neom. As the Public Investment Fund (PIF) has taken control of projects beyond Neom, it has sought to rein in budgets, while ordering deep cuts to spending across companies it controls. PIF’s governor, Yasir Al-Rumayyan, announced in 2023 that the fund, which has spent billions of dollars overseas on sports including golf tournaments, tennis and Formula 1 racing, would cut back its international spending by a third.

“Why wouldn’t we spend wiser if we could?” the Saudi minister of economy and planning Faisal Alibrahim told the Saudi outlet Arab News this month. “The first wave of Vision 2030 required us to deliver at any cost, but we’ve moved from that.”

At the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Saudi finance minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan spoke of “optimal impact at the right cost”.

Saudi officials have signalled renewed focus on delivering the infrastructure to host the World Expo in 2030 and the Fifa World Cup in 2034 though probably with fewer stadiums. Some parts of Neom are going ahead, including the port and industrial city of Oxagon. But the overall project was conspicuously absent from Saudi Arabia’s pre-budget government statement this year. That report detailed a pivot towards investing in AI, gaming and high-tech manufacturing. Recent reports suggest Neom could become a hub for data centres, taking advantage of cheap energy and unregulated land.

“The priorities have shifted since 2017: AI is one of the hot investments and they're looking to get into that,” said Tim Callen, a visiting fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute.

Saudi has made progress towards diversifying its economy, but two-thirds of government revenue still derives from oil, said James Swanston, an emerging markets economist with Capital Economics. “In terms of tourism, financial services and logistics obviously there has been a transformation in the past 10 years where these sectors weren't there before,” he said. “But to say they have been completely disentangled from oil is a stretch too far.”

While setbacks at Neom and other major projects are a symbolic blow to Vision 2030, economists say its objectives may be better served through investment elsewhere. “If anything, some of the money will be better used to diversify away from oil,” Zangana said.

While cutting back on some of the more extravagant projects, Saudi Arabia has also been putting more money into education, healthcare and pensions. “That’s really what the population wants more than some of these projects,” Zangana said.

But MBS can’t afford to walk away from Neom entirely. The futuristic megacity has become an emblem not only for Vision 30, but of his own rule.