The Observer has suspended publication of two articles about allegations of war crimes committed by the SAS in Afghanistan and a cover-up by senior officers.

Both allegations are being considered by the Independent Inquiry relating to Afghanistan, which wrote to The Observer this week requesting changes to the articles on the basis that our reporting breached restrictions the inquiry has imposed. We believe the changes would have fundamentally altered the meaning of our reports so we have chosen to take them down instead of amending them.

The inquiry has told The Observer that the restrictions have been imposed for good reason. We take a different view, and we will make our case to the inquiry at the first opportunity.

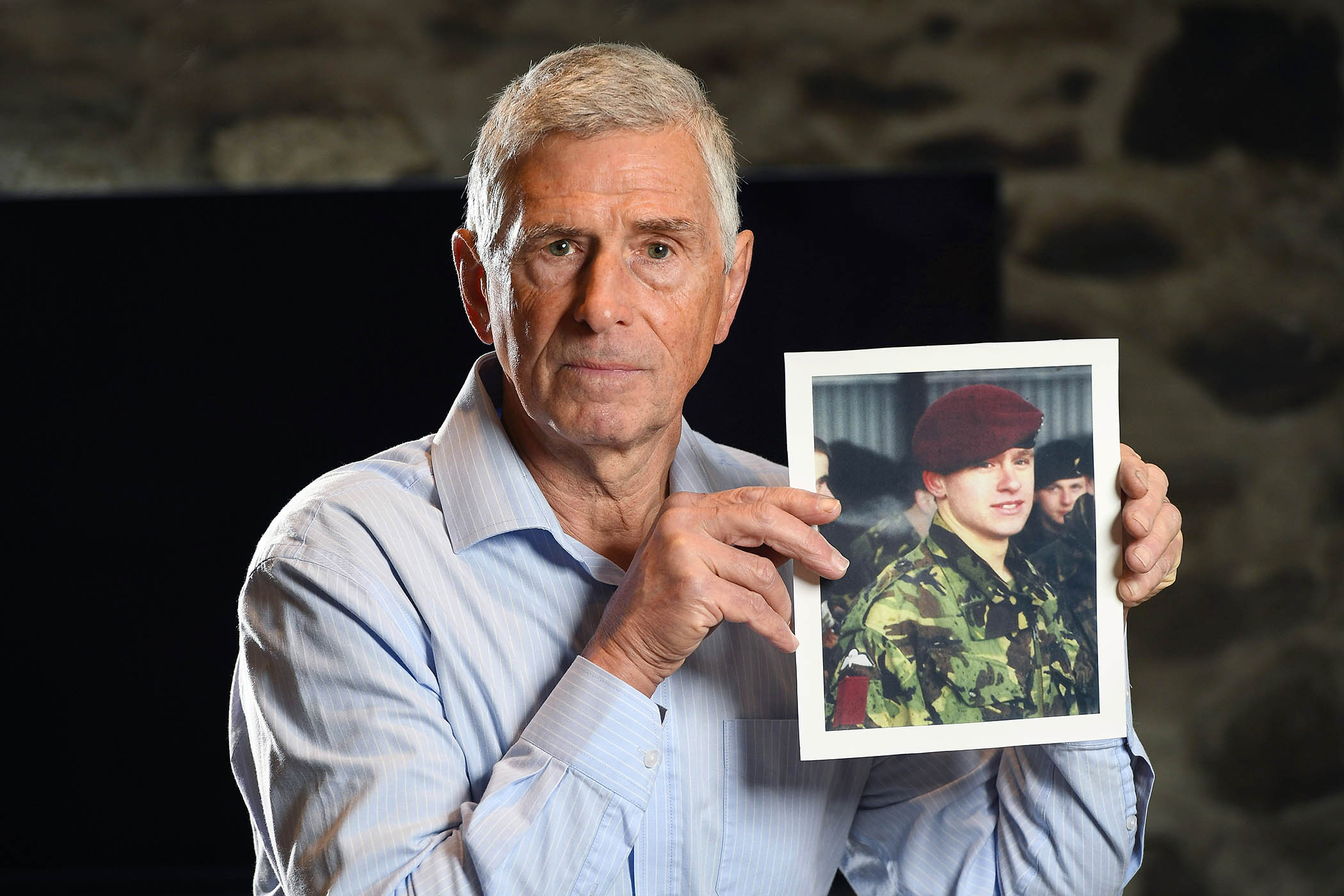

Photograph by Barney Low/Alamy

Related articles:

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy