Imran Uzbakzai was three and his brother Bilal one when they were orphaned on a night raid carried out by the British army in Afghanistan in 2012.

When the government announced a public inquiry into alleged war crimes – including the killing of the boys’ parents – they were 13 and 11.

By the time the inquiry concludes Imran could be nearly 20. Conceivably, he could be even older than that. The fact is, the inquiry cannot say when it might finish.

The slowness of the Independent Inquiry Relating to Afghanistan – the IIA for short – is one of a number of issues gathering around it. Over recent weeks, The Observer has spoken to people who are interested, in different ways, in seeing it succeed: witnesses, lawyers, campaigners. Their voices are a chorus of complaints in close harmony: the inquiry is ponderous; of course it has a difficult job to do in balancing security and open justice, but is getting it spectacularly wrong; and it “doesn’t give a shit” about witnesses.

‘They over-classify absolutely everything to cover up their work. And they’re using that to slow the progress of the inquiry’

‘They over-classify absolutely everything to cover up their work. And they’re using that to slow the progress of the inquiry’

Witness to the inquiry

When a public inquiry is being pelted with criticism from all sides it might consider two possibilities. If groups that want a different outcome from it are equally unhappy, perhaps it is picking the right path between competing interests. Alternatively, perhaps it is getting an awful lot wrong.

The IIA was announced in late 2022 to investigate allegations that UK special forces murdered civilians in Afghanistan between 2010 and 2013. Its chair, Lord Justice Haddon-Cave, let it be known that he expected to deliver an interim report within 12 to 18 months. There is no sign of it 36 months later.

As a rule, public inquiries are set up to answer a frustrated call for open justice – not only this one but Bloody Sunday, Hillsborough, and Grenfell before it. Each has had to contend with secretive institutions but none more so than the IIA. So much of the information in front of it is highly classified and many of the witnesses would understandably fear for their safety if their identities were revealed.

But even acknowledging all of that – as critics of the inquiry do – one question has become emblematic of a perceived instinct for secrecy at the expense, sometimes, of common sense: which special forces regiment is accused of the war crimes the inquiry is investigating?

Related articles:

There are only two realistic candidates: the SAS or SBS. The IIA’s focus is on the years 2010 to 2013, and if you were to ask Google which of those was the primary one operating in Afghanistan between those dates, you would get an answer. But you will not get one directly from the IIA.

The inquiry hides the two units behind the codenames UKSF1 and UKSF3, and demands that journalists do the same. But a glance at the opening statement from Richard Hermer (now the attorney general but in October 2023 the lawyer representing the families of Afghan victims) tells a story of confusion. In a transcript hosted on the inquiry’s own website, Hermer says “SAS” 109 times and “SBS” not at all. The situation is “farcical” says one lawyer who has looked into this issue; “absurd” says another.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The inquiry is stricter about policing the identity of three very senior officers whose conduct has been called into question. The Observer has been required to take down articles that the inquiry believed revealed the men’s identities, or risk a charge of criminal contempt. Others have been asked to do the same.

British and Afghan troops in Helmand

The counterpoint to the inquiry’s position is that it has become ridiculous: “It’s bonkers. The cat is out of the bag. If a lawyer had [the senior officers] as clients, sought anonymity and tried to justify it to a court, it just couldn’t be done. They’re everywhere in the media, and the links are there.”

In fact, as with the SAS/SBS question, you do not have to scramble around on the dark web to find the information: it is published on the inquiry’s website. One example among many: late last year the IIA released evidence from an officer codenamed N1466 who was critical of another officer, N1802.

The inquiry says N1802 was director of special forces (DSF) in 2011. There is only one DSF at a time, and an online search will reveal instantly who he was that year. Piecing together the simplest of jigsaws, the internet can name N1802 but, because of restriction orders put in place by the inquiry, The Observer cannot.

Two weeks ago, a former Conservative defence minister, James Heappey, told MPs on the defence select committee that the Ministry of Defence routinely over-classifies information and prevents parliamentary scrutiny. A witness to the inquiry agrees: “They over-classify absolutely everything to cover up their work. And they’re using that to slow the progress of the inquiry.”

That secrecy can have important effects on understanding current events as well as what happened 15 years ago. Since the inquiry got under way, N1785, a senior officer whose decision-making about reporting potential war crimes has been criticised, has been promoted to one of the highest ranks in the armed forces. The Observer and a thousand other people know who he is, and the information is freely available online, but it is not possible to link the officer’s name to the cipher N1785 without risking legal action.

The Observer asked the IIA why it clings to its injunction against identifying the SAS or SBS. The inquiry replied that the BBC has challenged that restriction (in the teeth of opposition from the MoD) and that Haddon-Cave will make a ruling on it some time after 16 February. It is a defence that opens up another flank for attack. Because it was in April 2025 that the BBC asked permission to say out loud either SAS or SBS.

Even if Haddon-Cave gets his skates on after 16 February, it will have taken him the better part of a year to rule on what some critics believe is one of the simplest questions he is likely to face.

Why are the wheels grinding so slowly? The demands of national security and the safety of witnesses certainly put sand in the gears, and the process of managing them is cumbersome. Like other inquiries before it, the IIA holds some sessions “in open” and some “in closed” to protect people and classified information, and only participants with high-level security clearance are allowed into closed sessions. The deal for those who are excluded is that a “gist” of evidence given in secret will be circulated later.

It is impossible to see from outside the complex legal and procedural arguments that surround “gisting”, but there may be a clue in the length of time it takes. In the case of N1466, the inquiry says his evidence about N1802 was heard in a closed session in summer 2024. The gist was made public in December 2025. Perhaps it is coincidence that a gist implicating a very senior officer took that long to produce; perhaps not.

Last week in a court case related to the inquiry the MoD complained that a gist had already taken more than five months to emerge for reasons, the court was told, “we simply do not understand”. Delays of more than a year are believed to be common. The inquiry says the worst hold-ups were caused by a legal challenge from the MoD that has now been rejected, but its critics are not buying.

Offsetting every criticism of the inquiry is an understanding of the difficult job it has to do. Potentially important witnesses have turned down requests to appear for fear of incriminating themselves. The inquiry told The Observer that it was not struggling to find witnesses prepared to step forward, but it did not go unnoticed last year that eight former soldiers were prepared to give evidence anonymously to the BBC’s Panorama, and none of them was willing to appear before the IIA.

One retired officer who did take the stand put his finger on what he thought was a critical moment, when the inquiry threatened to throw the book at a former Tory veterans’ minister, Johnny Mercer.

Mercer had given a second-hand account to the inquiry from a source he described as vulnerable. Under extreme pressure from the inquiry – including, at the outer limit, the prospect of jail time – he refused to break a promise he said he had given to keep secret his source’s identity. It was a moment of drama at the inquiry, and the ex-soldier says it turned heads.

“[There are eyewitnesses] who won’t come forward because they don’t want to be treated like Johnny Mercer. If you think you’re a vulnerable witness why on earth would you come forward after that? It was really, really stupid.”

On these crisscrossing tightropes between openness and national security, between fairness and speed, the IIA totters slowly along. Is this just the way it goes? After all, a three-year-old who was caught up in Bloody Sunday in 1972 would have been 29 when the Saville inquiry was announced and more than 40 years old before its findings were published. Yet, in spite of all the time that passed, and the people who died waiting, the signs are that history will judge Saville to have been worthwhile.

But an observation about the Afghanistan inquiry made by someone who follows its every twist and turn prompts a smile of recognition every time it is repeated: “It’s the least public public inquiry there has ever been.”

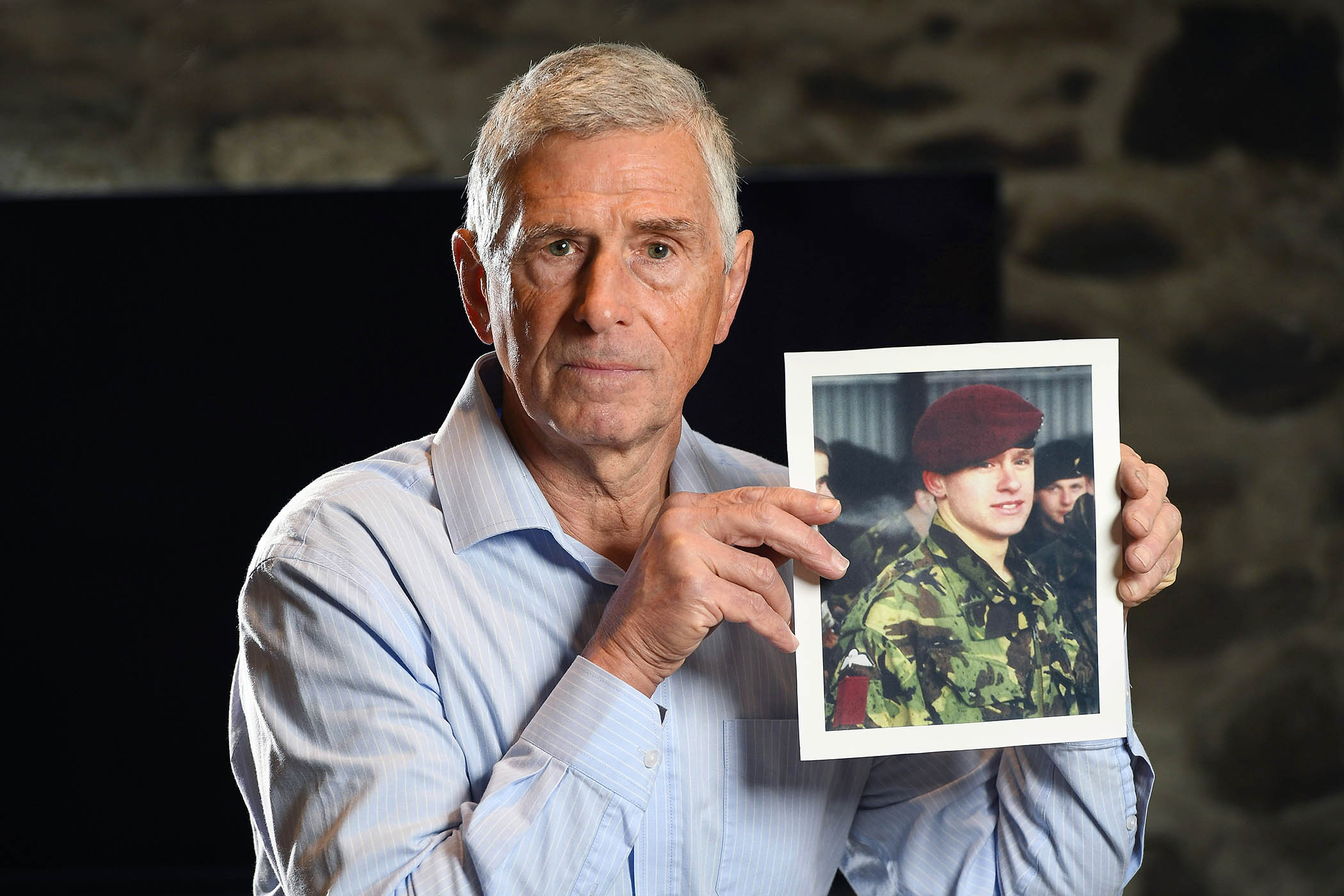

Portrait Julian Busch. Other photograph Marco Di Lauro/Getty Images